Come to the Edge: A Memoir (23 page)

Read Come to the Edge: A Memoir Online

Authors: Christina Haag

Tags: #Social Science, #Popular Culture, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #General, #United States, #Personal Memoirs, #Biography, #Television actors and actresses, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous

A red truck drove up alongside me. It was Pat from the Inn. His hair, once wild, was short. He leaned over the passenger’s seat, and we caught up. He was married now with daughters. He asked if I wanted a ride back to Greyfield.

“Thanks, I’m going to walk.”

“Looks to be a downpour.”

“I’ll take my chances.”

He stared at me, bemused. “You’ve changed.”

“How’s that?”

“You don’t remember?” He grinned as if it were an answer. “You don’t, do you?”

I shook my head.

“When you first came here years ago, you

really

didn’t like the rain.”

It took me a moment. A dry truck. A flowered dress. August heat. A boy I loved. I began to smile, remembering. “No … No, I didn’t. But I like it now, I like the rain.”

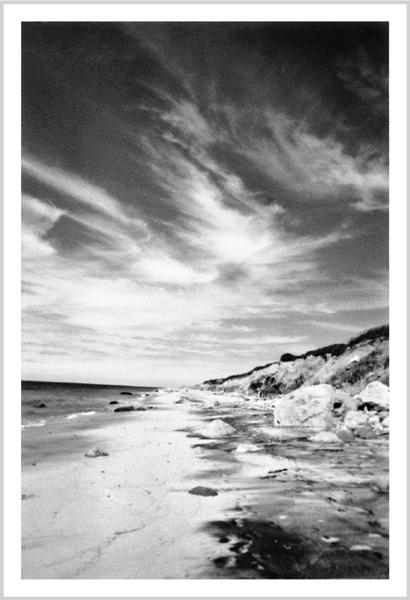

I watched as the truck pulled away. It turned inland, got smaller, and disappeared over the high dunes on the path to Greyfield. I dug my hands into my pockets and kept walking. I walked past the Rockefeller gazebo and the Nightingale Trail. I walked past a herd of horses at Sea Camp and the salt marshes near Dungeness. I walked as far as I could on the empty beach in the cool winter rain.

I had bought him a compass, but I never gave it to him that night. It was there in the pocket of my jacket as I walked, my fingers warm on the metal. I kept it with me for a time—in a drawer or on my bureau; sometimes I held it. Until one day, without knowing how, I could no longer find it.

He had called me his compass, but he was wrong in that.

He had been mine.

After

Remembrance is a form of meeting.

—

KAHLIL GIBRAN

There is a land of the living and a land of the dead

and the bridge is love, the only survival,

the only meaning.

—

THORNTON WILDER

I

t was early June 2000, almost a year to the anniversary of his death, and I was driving across the country with a man I was in love with, afraid of the grief I would feel the closer we got to New York and July 16. We’d been in the Grand Canyon for two nights, and John had been present in my mind. He loved this place. Ten years before, we’d planned to go, but a play had kept me in New York, and he had gone without me. I got a postcard from him, telling me how much he loved it, how hot it was, and how he would have much preferred me in the sleeping bag next to him rather than his friend Dan, aka Pinky. “Ha! Ha, Baby!” he wrote.

There’s a picture he gave me: John in a tank top, green-and-black nylon shorts, mirrored glasses, and hiking boots, dancing the funky chicken in celebration of the seven-thousand-foot descent on the Bright Angel Trail. The light is failing, and there are shadows on his face.

On the drive northeast to Durango the next day, we stopped at the Navajo National Monument to see the ancient cliff dwellings. We paid the fee and walked through the small museum. My friend went on ahead while I lingered by the headdresses and the labeled pottery shards. When I was done, I stepped into the open-air courtyard and began to cross toward the turnstile entrance to the dwellings across the gorge. Out of the corner of my eye, I noticed a small girl, maybe five, twirling like a dervish for an older couple, who sat with folded hands, watching. You couldn’t help but watch. Half-wild in a dirty T-shirt—with hair in her mouth and her arms spread wide—she lifted her face to the sky, as if she was pivoting from the very center of her heart.

What freedom

, I thought. I used to be that girl: asking people in airports if they wanted to see me dance, singing songs in kindergarten I made up on the spot instead of bringing a favorite toy to show-and-tell. I had a dispensation from Miss Mellion and even a title, “Make-Up-Song Girl.” I used to be that girl and I wasn’t anymore.

I smiled, dazzled by the heat. Then, at the turnstile, with my eyes on the ruins ahead, I heard her say something to her grandparents, to the bright sky, and to no one in particular. “Do you know where John Kennedy is?”

How odd, that I should pass by just now

. Maybe she meant his father. Maybe I hadn’t heard right. The heat.

She kept spinning. “Do you

know

where he is!” she insisted in singsong. “In the ocean? … Noooo. In heaven? … Noooo. In the Indian spirit world?” She paused briefly, then answered herself, “Yes! Yes! He’s in the Indian spirit world!”

Laughing, sibyl-like, she spun faster.

I stood for a moment, half-expecting her to disappear. When she didn’t, I lowered my hands to the shiny metal bar in front of me and pushed until it clicked. I didn’t look back until I’d reached the bench where my friend was waiting. I sat near him, unable to grasp what I had just heard. Across the gorge, shadows began to dart like swallows from the ancient portals in the rocks, and finally, when I could speak, I told him the story.

It was only later that I knew, on a trip I took alone to Gay Head and the lighthouse, to the wild grasses and the smooth road near his mother’s house called Moshup Trail and the view of the sea where the plane had fallen. I stayed at a bed-and-breakfast nearby, an old whaling captain’s house, with sand on the floor and a ball-and-claw bathtub in the small room. It had been eight years since he’d died. I needed to go back, but on the ferry from Woods Hole, I argued with myself.

What are you doing, you don’t need to come here; you’ve already said your goodbyes

.

At dusk, on the day before I was to leave, I walked back from the beach through the thick dune to the road. It was September and warm, and for some reason I thought of the girl. I’d remembered her from time to time, as if she were a piece of a puzzle. Her spinning; her words; the laughing. And the precarious fact that my lingering over a particular shard of pottery had made me a witness.

By then, the sun had fallen fully, vanishing into the water at the end of the cliffs, and I knew, in that violet light, miles and years from where it had happened, that I had been given a gift among the rocks and the wide sky of the Anasazi. One of acceptance.

I believe God speaks through others. Maybe John’s spirit is at peace in the places he loved. Dancing in a canyon. Swimming off the Vineyard. Flying in the clouds. In all the wild places, where he was free.

O

n May 3, 2004, I was driving north on Highway One thinking about silence. When the car began its climb up the narrow coast road, passing the sign that divides Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties, I opened the windows and let the sea breeze in. It was the heat of the day, and the sky was cloudless. On the passenger’s seat beside me was a white cowboy hat with a blue jay feather tucked in its brim, a present from my friend Rebecca. Tomorrow was my birthday. I would turn forty-four, and I had just been diagnosed with breast cancer.

I had seen the heavy wooden cross sunk into the side of the road at Lucia many times in my sojourns to the Central Coast over the past fifteen years, but I’d never stopped. Like a pilgrim to the sexy stuff, I kept moving on to the heart of Big Sur, to the places whose names were chants—Deetjen’s, Nepenthe, Esalen, Ventana. But less than two weeks before, when I heard my surgeon, Nora Hansen, say the words that left me with none, when she held her blue eyes steady on me as I cried, I knew this was where I had to come. I knew that somehow, in this place I’d never been, I would be changed. Against the advice of doctors and family, I delayed the second surgery and booked six days of silent retreat at the Hermitage, a Camaldolese Benedictine monastery high in the Santa Lucia Mountains.

At Ragged Point, I stopped for gas and to stretch my legs. I had driven more than 250 miles from LA with only the radio for company, and for the last hour or so, it was static. Harleys in caravan roared by on their way to San Francisco.

Silence. A silent retreat

. What was I thinking? Was I crazy? I’d been baptized, and my bloodlines stretched back to the peat of Galway, Cork, and Kerry, but I wasn’t sure I was still a Catholic.

And how could I be silent? In the past month, my mind had become like an unruly child, chattering, wandering, obsessing over details, ever since the mammogram report came back “Birad IV: Suspicious Finding.” Sleep meant nothing; stillness was a memory. I spent hours on the computer memorizing medical studies, percentages, risk factors. I stared at the ghostly pattern of calcifications, a crescent of moondust on a negative. To the handful of people I told, I talked of nothing else. I was gripped by fear—fear of death, fear of change. I had no script for what was happening to me. And at that moment in the parking lot at Ragged Point, I was terrified of silence. I pulled the top strap of the seat belt under my chest so it wouldn’t hit the stitches, and started the car anyway.

At Lucia, I came to the cross I had passed before and took a hard right. The long afternoon light had begun and rabbits darted on either side of the car. I downshifted and drove up the two-mile dirt switchback. At the top was a simple church built in 1959, the flax-colored paint faded. A bookstore stood alongside it, with the monks’ enclosure behind. The smell of chaparral was everywhere.

“We’ve been waiting for you. Welcome.” Father Isaiah was a slender man, bearded, in a white robe and Tevas. We had spoken on the phone two days before, and as he led me to the retreat house, a semicircle of nine rooms that faced the Pacific, he explained the rules. Silence was to be observed except in the bookstore. Meals were to be taken alone in one’s room. Food and showers could be found in the common area at the center of the house. A hot lunch was prepared daily. If I wished, I could join the monks for the Liturgy of the Hours, but it wasn’t required. Nothing was.

“Vigils begin at 5:30

A.M

. And Lauds are at 7:00.”

I didn’t know what Lauds were, but I nodded as if I did.

We reached the retreat house. Each of the doors had a small metal plaque with the name of a saint on it, except for those at either end. Father Isaiah stood by a saintless one. It had an emblem of the Sacred Heart and my name on a slip of paper tucked into the edge of the rusted metal. Before I had time to wonder at the synchronicity, he opened the door. The room was clean and small: a narrow captain’s bed with a wool blanket, a desk and chair, and a pine rocker. A large picture window opened on a tiny private garden, where at dawn and dusk, deer, fox, and quail would pass.

“The monks are available for spiritual direction. If that’s something you want, just ask and I’ll arrange it.”

I dropped my bags and took a breath.

“If you feel like talking, come find me in the bookstore,” he said brightly, and set off for Vespers before I could answer.

I didn’t make it to Vespers that night. Or to Lauds the next morning. I don’t know how long I stayed in the simple room with the hard bed and the window on the world. There was no one to come get me, no one to answer to, no one to buck up for. The bare walls were a comfort, and the silence I had feared, a relief. I ate the monks’ food. I slept. I read. I wept until there was nothing left. Pain broke me open. In the darkness, I let it cradle me; I let it fall all around me.

On the second morning, lulled by the bells, I trudged to the church before dawn and joined the monks for Vigils. They sat, white-robed in the nave, facing not the altar but each other. I saw Father Isaiah, his clear voice leading the canticles and antiphons, the psalms and the Benedictus. I slipped into the back row. For the next four days, I fell into their rhythm—the rhythm of men on the mountain and the consecration of each hour of the day through prayer and contemplation. I didn’t have faith, not then. But I followed theirs. The words I had heard before, somewhere in my childhood, but now they were rich with ancient meaning. Now they were words to rest in, and I chanted along with the monks.

Gloria Patri et Filio et Spiritui Sancto … et nunc et semper et in saecula saeculorum

.

After Lauds, I walked up a rise near the retreat house. Tangled in high grass by a large rock was a single wild iris, a small miracle. I climbed up the rock and wrapped my knees to my chest. On my back, I felt the beginnings of the sun’s warmth, golden fingers that reached over the gray morning hills. I thought of those whom I had loved deeply, those who had loved me well and were no longer alive. My father, my grandmothers—the one with the medallion and the one who had married in red. My friend Christopher, who’d died of AIDS three year before, and Jonathan Larson, the young composer of

Rent

, whom I had known briefly. I thought of John’s mother. They had believed in me, and their belief was like a hand that pushes you up the last part of the mountain or points you down a path, overgrown, you hadn’t known was there, but once you’re on it, your feet dusty with it, you find it was the way all along.

My father had been dead for almost twelve years, but sitting on that rock with the sun behind me, I missed him more than ever—the long lunches at a favorite Chinese restaurant on Third Avenue, his deep embrace, his dogged optimism, even his anger. Whatever his flaws, he was there for me in a crisis. He fought for me, and he relished the fight.

After his stroke in the spring of 1987, he began to regain his speech and the ability to walk, but this vital man, once the life of the party, called Fun Daddy by my friends in grade school, would lie in a darkened bedroom most of the day staring at the ceiling. “Just resting,” he’d murmur. I was twenty-six and believed that everything improved, everything went forward if you just tried hard enough. It was what my father had taught me. I believed that with the right doctor, the right drug, the right diet, he would get better; he would become my father again.

During those days, Mrs. Onassis always asked after him. Even before he was sick, we would trade tales of our fathers, of their charm and panache, of how well they danced and how well they laughed. There was one story in particular she smiled over. Her parents had recently divorced, and Jack Bouvier would arrange to borrow dogs from a neighborhood pet store for his weekend visits—incurring the wrath of his ex-wife and the delight of his daughters.

One July morning on Martha’s Vineyard after John had gone windsurfing, she asked how my father was. In the front foyer, with a wall of burnt orange leading up the staircase to her bedroom, I found myself crying in front of the one person I never thought I’d cry in front of. She guided me to a tufted chair nearby and let me talk. Her eyes grew moist. Sometimes she nodded, but her gaze never left me. Then she spoke.

“All will be well, I promise.”

“Really?” I searched her face for clues.

How could she know? But then I thought, if anyone could discern the impossible, she would be able to—I endowed her with that much wisdom. Like Cassandra, through beauty and sorrow she had a gift, and somehow she knew that my father would come back to me. But that is not what happened. My father did not get well. For the next five years, there were ebbs and flows of health, a slew of operations, depression, painful physical therapy, the amputation of his right leg, until his death alone at Beth Abraham in the Bronx on a frigid November night in 1992.

All will be well

. Seventeen years later, I knew her meaning. You will find the courage to walk with grace through whatever life gives you. It’s what she had done, and I wanted to hear her say those words to me now, as I doubted my ability to walk through the next hour, to put even one foot in front of the other. A long relationship had ended almost three years before, and although I had good friends and family, cancer is isolating. Loved ones don’t always know how to help you. It makes them afraid, and I felt bereft and alone.

John and I had once climbed the hills just north of here. As he often did when we hiked and I flagged near the top, he told me to keep going. He took my pack with his and walked behind, his free hand prodding me along.

Couragio

. As the second surgery drew closer, I wanted a hand to push me forward, a lover’s arm draped around me, someone to carry my pack for just a few steps. I wanted someone who loved me to tell me not to be afraid. And it seemed, on that rock, I wanted to talk to the dead. In moments of great need, time becomes a trick, and the sky can open. And so it was. Perhaps it was mere longing, but I felt him there with me, his arm heavy on my shoulder, his head dipped toward mine.

We had come to Big Sur, both of us for the first time, for Easter in 1990. By the time the year was up, we would no longer be together. We stayed at the Ventana in a suite with pitched cedar ceilings and a hot pool that steamed at night in the spring rain. We hiked and bicycled and gathered giant pinecones on a mountaintop and talked about our future, a thing we didn’t always do. At Nepenthe, we bought postcards we didn’t send and books we didn’t read and kept returning to the Henry Miller Library, which, regardless of the hours posted, was always closed. On Easter Sunday, we went to Mass at a chapel in the forest and stood in the back. We huddled on the windswept beach at Pfeiffer, the sand whipping our faces, a beach I would return to years later with another lover on a windier day.

The morning we drove to San Francisco to catch our flight back east, he pulled the rental car over at an outlook north of Partington Cove. We stood there on the cliffs, silent, breathing our last of the sea air before the drive north. The navy water below was studded with whitecaps and sea otters. Above, birds of prey circled.

“Look—red-tailed hawk.” He took his hand from my waist and pointed up, not excited but pleased. He had an affinity for these birds, and because they are the most common of hawks—adaptive, with territory in desert and forest from Canada to Panama—he was always pointing them out. We’d stop a moment, watch them soar, pay homage. It seemed to calm him that wherever he was, red-tailed hawks were there, watching over him like wild kindred spirits.

I raised my head, following his gaze, and, squinting, tried to make out the buzzards from the hawk. He explained the differences as he always did. Head, belly, tail, wingspan. I’m not sure whether I could see them or not, or whether I just liked hearing him tell me. It was something that made me love him fiercely, this conviction of his that it was of utmost importance that I, as a member of the human race, know the difference between a red-tailed hawk and a turkey buzzard, and he wouldn’t quit until I did.

As I scanned the sky, he told me that hawks bond beyond mating, some for life, and that when they court, the males make steep dives around the females until their talons lock and they spiral together to the ground.

“That’s awful—you’re making it up!” I cried.

Pleased by my response, he kept on.

“But you, Puppy, the way

you

will tell red-tailed hawks is by the way they

shriek

when they are hungry for rabbitsandsnakesandsquirrels, just like when you are hungry and you shriek and squeal.”

“I do not. Stop it, John!”

“Oh, but you

are

right now.”

“You’re tickling me!” I yelled, and ran to the car. We were still laughing when we pulled up to the general store for sandwiches. We both knew, when he said I was hungry, that it was he who needed to eat.

Passing over Bixby Bridge with Big Sur fading behind us, I turned and touched his cheek. “King,” I said to him, “let’s come back next year.”

The afternoon before I was to leave the Hermitage, I met with Father Daniel for spiritual direction. I walked to the chapel fingering a jade Buddha on a red string that my brother had brought back from China. He had given it to me the day before the biopsy, and now it hung, day and night, around my neck. The doors of the church were heavy. I opened them and met a round man in a white robe who looked like he had lived. He led me to a small room near the font of holy water, and when he quoted Jung and Robert Johnson, I liked him at once. For more than an hour, I told him about my life. I told him everything I could remember, the last failed love affair, guilts I had forgotten, anything that weighed on me. I even spoke of the pain I’d felt years before when I’d found out that John had gotten married on Cumberland. It surprised me. So much time had passed, but an inkling of it was there, deep within me.

I told him how afraid I was. I said that now, when I needed it most, I could not pray. It was as though my knees would not bend. As I spoke, I realized I was ashamed I had cancer.