Color: A Natural History of the Palette (45 page)

Read Color: A Natural History of the Palette Online

Authors: Victoria Finlay

Tags: #History, #General, #Art, #Color Theory, #Crafts & Hobbies, #Nonfiction

In fact for many years this painting was not even believed to have been painted by Michelangelo at all, with an all-important “?” following every attribution. National Gallery curators recently described it as “among the most troubling mysteries in the history of art,”

17

adding that although scientific tests suggested it really was the master’s hand that drew this strange scene of personal suffering, “pockets of resistance remain.” The British forger Eric Hebborn liked to speculate that

The Entombment

was “the work of a Renaissance colleague”—a man who had perhaps read Cennino’s book and had a talent for drawing if not for coloring in. “If so, well done!” he wrote approvingly.

18

CHARTRES BLUE

Throughout my travels in Afghanistan I had often remembered my other most holy blue: that experience, which I described at the beginning of this book, of seeing blue light dancing through a cathedral at the age of eight and wanting to follow it, wherever it took me. As a child I wanted that recipe for blue to be lost so that I could find it, but then much later I learned that the “Lost Blue Glass of Chartres Cathedral Story” was a myth. We have not lost the recipe for that blue, contemporary glass-makers told me strictly, and I felt foolish for asking. It is a relatively easy thing to make a good blue, and involves certain proportions of cobalt oxide in a melted soup of silicon. And yet there is another more important way in which the myth is based in truth. We have not lost the recipe for Gothic blue; it is just that the world has changed, and we cannot make it anymore.

When a cathedral was commissioned in Europe in the 1200s there were many things to organize. Funding was vital; the site— on flattish ground yet where it would dominate the medieval city— was important; the craftsmen had to be booked and the wood and stones ordered. It could take decades. Once the walls and the roof were up, it was time to bring in the painters (all cathedrals were painted in bright colors) and the glaziers. It is mostly only the work of the latter which remains.

The men who made the stained glass were strange folk. They were itinerant craftsmen who would travel from cathedral to cathedral, going wherever they were wanted. And at the height of the Gothic cathedral construction craze, it seems they were wanted everywhere, and the best of them could ask high prices. They set up their camps on the edge of the forest. It was a highly symbolic place to stay—the border between civilization and lawlessness. Forests were seen as dark places where strange spirits dwelt, and where ordinary folk should not go. They were therefore the perfect locations, cosmologically speaking, in which to perform the transformational magic involved in making glass. But the forest was also a practical place for the glaziers. Wood, in huge, unenvironmental quantities, was the main raw material—it not only fired the furnaces, but together with sand was one of the two major ingredients of glass.

The metalworking monk, Theophilus, described

19

in the twelfth century how glaziers used three furnaces—one for heating, another for cooling, and the third for melting the blown glass into sheets. The color tended to come from the metal oxides (manganese, iron and others) that were naturally found both in the beech wood and in the clay of the jars that the glass was heated in, and the final hue was hard to predict. “If you see any pot happening to turn a tawny colour, use this glass for flesh-colour and taking out as much as you wish, heat the remainder for two hours . . . and you will get a light purple. Heat it again from the third to the sixth hour and it will be a reddish purple and exquisite,” Theophilus wrote, although Vitruvius

20

had written in Roman times about how glass-makers made blue glass (and a sky-blue pigment powdered from it) using soda mixed and melted with copper filings.

Nobody quite knows who the glaziers were—they rarely signed their names—although we do know of a Rogerus who was brought from Reims to Luxembourg to work on the Abbey of Saint Hubert d’Ardenne, and there is a record of a man called Valerius who fell from a scaffold while installing stained glass in the Abbey of Sainte-Melanie in Rennes, and bounced up unharmed. But mostly it was just known that they came when they were summoned by the Church, that they sometimes spoke in strange accents, and that when they left, the new cathedral was alive with colored light. Mothers may have warned their children to stay away from the glass camps, because they would have seen the gypsy qualities in these men. But if, as a medieval child, you had crept to the fire where they were transforming sand into gems— blowing this beautiful substance into existence at the end of iron blowpipes—and had listened from the darkness, you might have heard wonderful stories of other worlds. They might have discussed the saints and the proverbs that were in the lead frames they were filling with their colors. But more likely they would have talked about the curious things they had seen, and the strange people they had met.

Today our glass-makers don’t camp out for days on the edge of the forest, and they have efficient ways of protecting their vats from floating ash and over-flying birds. Perhaps it was those tiny imperfections—meaning that the warm sunlight scattered unevenly as it passed from one side of the glass to another—which made me feel on a day after rain in Chartres that something holy was there too. But perhaps those campfire stories were stirred into the slow-melting pot as well, mixed carefully into the blue and red fluxes, shifting the Gothic glass imperceptibly from the realm of craft into that of art.

THE VIRGIN’S ROBE

Chartres gave me another postscript to the story of blue—an unexpected one. On my journeys to Afghanistan I had found out where the color for the Virgin’s veil should have come from, and I thought I had found out why it was so often blue. But I had never thought I would find out what color the veil really might have been. And in Chartres, I found an answer of sorts. The reason this town is such a pilgrimage center is because in around 876 Charles the Bald, the grandson of Charlemagne, gave Chartres a special gift. He gave them the veil said to have been worn by Mary, as she stood by the cross and wept.

21

Today’s cathedral is the fifth one on the site; the others were burned down or ransacked and each time, the story goes, the people pragmatically said the Virgin must want something better, so they raised the money and rebuilt the structure. The last big fire was in 1194, and only three things were saved: a set of three saints’ windows, a stained-glass picture of the Virgin and Child from 1150, which is now known as “Notre Dame de la Belle Verrière”— Our Lady of the Beautiful Glass—and the famous relic.

22

The veil shown in the stained-glass picture of “la Belle Verrière” is a pale color, light enough to allow the sun to flood through and depict the young woman’s purity. But it is unmistakably light blue, and worn over a blue tunic. Those 1150 glass-makers would have had the “real” veil to model their design on, which is curious, because when you see the precious relic in its gold nineteenth-century box—a humble scrap of material to the glory of which this whole cathedral was dedicated—it is not blue at all. More of an off-white: the faded clothing of the melancholy mother of a martyr. Had he seen it or heard of it, and had he wanted to go for veracity rather than value, Michelangelo could as well have painted his mysterious corner figure with lead white, mixed with a little yellow. And yet if he had, I would not have had this story.

9

Indigo

Goluk: “We have nearly abandoned all the ploughs; still we have to cultivate Indigo. We have no chance in a dispute with the Sahibs. They bind us and beat us, it is for us to suffer.”

DINABANDHU MITRA, Nil Darpan, 1860

“The fact is, that every one of these colours is hideous in itself, whereas all the old dyes are in themselves beautiful colors; only extreme perversity could make an ugly colour out of them.”

WILLIAM MORRIS

1

My father lived in India for three years in the 1950s, before he met my mother. He used to tell me stories about Bombay mangos, Madras spices, and a puppy called Wendi, who was a great coconut hunter. But what really caught my attention was the club he belonged to in Calcutta which was, he always said, set in an indigo plantation. I daydreamed of the Tollygunge when I was a child. I wasn’t in the least bit interested in the golf course, polo games or colonial bars. But how I thought about the indigo. I imagined tall trees rising to a cathedral canopy, their slim purple trunks as lovely as kabuki actors in kimonos. And I pictured men dressed in Gandhi-white robes and pink turbans strolling through dappled glades to tap a rich blue dye into beaten tin pots.

Once upon a time, or actually several times upon a time, indigo was the most important dye in the world. At one point it helped prop up an empire, and then later it helped destabilize it. Ancient Egyptians used indigo-dyed cloths to wrap their mummies, in Central Asia it was one of the main colors for carpets, and for more than three centuries in Europe and America it was one of the more controversial of dyestuffs, and it would have been familiar to people of many nationalities. So it is rather telling that by my childhood in the 1970s I had no idea what indigo was, only that it sounded nice. And many years later, when it came to setting out on my quest, I still casually went off looking for trees.

“Indigo” is a word like “ultramarine”—it refers to where the color historically comes from, rather than what the substance actually is. So, just as ultramarine is a translation of the Italian for “from beyond the seas,” indigo is derived from the Greek term meaning “from India.” Sometimes the Europeans were fairly slapdash about what they described as coming from India—“Indian” ink, for example, was actually made in China—and they would cheerfully lump anything that came from roughly that direction into the category of Indian things. But in the case of indigo, they were fairly accurate, and so it turned out I had accidentally been right to have started thinking about indigo in India, even if it took me a while to find it there.

Indigo cultivation probably existed in the Indus Valley more than five thousand years ago, where they called it

nila

, meaning dark blue. It spread north, south, east and west as the best things often do—the British Museum owns a tablet of Babylonian dye recipes from the seventh century B.C. which indicates that indigo was already being used in Mesopotamia 2,700 years ago—and when the Europeans turned up in Goa in the early 1500s, greedy for profits from exotic trade, they found enough Indian indigo to be able to throw it into their holds along with camphor and nutmeg (from what is now Indonesia) and embroidered silks from all over the East. Indigo wasn’t a new substance to Europe—it had been imported in small quantities since classical times for use as a medicine and a paint (Cennino had suggested slipping a bit of Baghdad indigo into clay to make a fake ultramarine for frescos), but now Portuguese, and later British and Dutch, traders were about to market it as a wonderful dye. They were confident their new color would be a winner. Indigo was not only the best blue they knew, but it had the extra cachet of being from an exotic part of the world with an exotic name at a time when the “mysterious Orient” was just about to be the rage. But before anyone could make a success of this colorful crop from the Indies, the traders first had to deal with what was almost a monopoly on blue held by the European growers of another plant. A plant called woad, which produces indigo, but much less than comes from the plant that is actually called “indigo.”

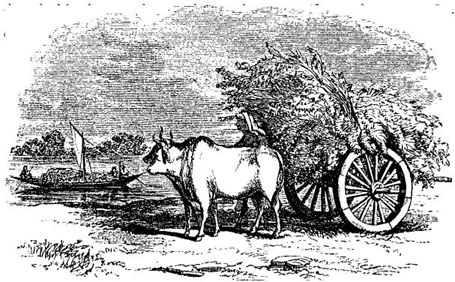

Cart full of indigo

A FIGHTER’S WEED

Woad is a funny word—it sounds like “weed,” and in fact the two words have the same origin. The seeds of this mustard plant,

Isatis tinctoria

, float so easily in the wind and settle in so many different soils that anything unwanted in gardens or fields became known laughingly as a “woad” and later, with a vowel change, as a “weed.” It is so prolific that even today it is banned in some American states—Utah is still overrun by the descendants of seedlings planted by Mormon dyers in the nineteenth century, and California and Washington also try to chase away the blues with strict legislation. The British tend to think of woad as a war paint—a symbol of the fierceness of Ancient Britons before the Romans conquered the country nearly two thousand years ago. Schoolchildren learn that Queen Boadicea wore it as she rode fearlessly on her chariot against the invaders, and that the great warrior King Caractacus daubed his body in woad before every battle.

I visited Caer Caradoc—the hill near Church Stretton in Shropshire where Caractacus is said to have made his last stand—on a November afternoon. I tried to picture the wintry morning in 51 A.D. when a band of warriors may have stood there painting their bodies with blue dye and later lost Britain for the Britons. The wind whipped around both the rocks and my ears as I walked up the steep hill; it sounded like distant war-whoops, and made it easy to imagine an upstart leader—the charismatic son of Cymbeline— encouraging his troops before the battle. This was the second time the Romans had invaded. A century earlier, in 55 B.C., Julius Caesar had arrived with five legions, and had fought his way as far as St. Albans. In his

Commentaries on the Gallic Wars

, Caesar wrote about the peculiar practices of the Britons. The men, he said, lived on milk and meat, dressed in skins, and shared one woman between ten or twelve of them. “All the Britons stain themselves with

vitrum

,” he continued in a sentence that has been frequently dissected by historians, “which gives a blue color and a wild appearance in battle.”