Color: A Natural History of the Palette (26 page)

Read Color: A Natural History of the Palette Online

Authors: Victoria Finlay

Tags: #History, #General, #Art, #Color Theory, #Crafts & Hobbies, #Nonfiction

But no offerings to their own God seemed to help the Jews in those difficult days of the 1490s. As Martinengo may have found, even North Africa was not a reliable refuge. There were stories of the Moors banning Jews from the cities, and forcing them to stay in the countryside—where they starved. So if our refugee had the money he would have continued along the coast, looking for somewhere to live peacefully. And the next major stop—avoiding Sicily, part of the Spanish empire and another place from which Jews had been exiled—would be Alexandria. In that busy port, named after Alexander the Great, a wandering lute-maker would have found a marketplace full of exciting materials.

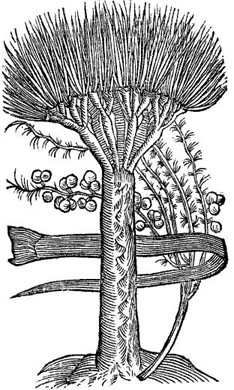

Dragon’s blood tree seventeenth-century woodcut

One of them was “dragon’s blood,” which had been carried up the Red Sea in ships from Yemen and perhaps even from the islands that today make up Indonesia. If he had taken the time, Martinengo could have sat down in the market and heard the stories of how this brownish-red powder had gained its curious name. For a few coins, people would have told him as many tales of saints and princes and maidens and great angry green beasts as he would have had the time to hear. Perhaps he would have been disappointed to hear eventually that it was simply the sap of a special “dragon’s blood” tree, so called because the resin was so dark it must surely be reptilian. Cennino Cennini, a century earlier, hadn’t liked it. “Leave it alone,” he warned his readers. But the colored resin is highly prized for violins, even today.

The sheer range of oils from nuts and seeds in the bazaars of North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean would have been intoxicating. Linseed oil was the new material for artists, and had recently replaced tempera as a binding ingredient. But there would also be oils from cloves and aniseed, walnut and safflower, as well as from the seed of the opium poppy.

7

There would have been many gums and resins in these markets for our lute-maker to bind his wood with: sandarac resin from North African pines, gum arabic from Egypt, gum benjamin (now called benzoin) from Sumatra; gum tragacanth from Aleppo, which would be sold as thin and wrinkled worm-like pieces of shrub.

8

Gums and resins come from trees—but gums turn to jelly when they are mixed with water, while resins only dissolve in oils, alcohol and the spirit of turpentine.

The tale of how the Ottoman ruler Bezar II had mocked Spain for expelling the Jews is perhaps apocryphal, but news travels fast among beleaguered people, and the legend of how he had said: “You call Ferdinand a wise king, he who impoverished his country and enriched mine” may well have travelled down to the Jewish communities in Egypt within months. They would have found it immensely comforting. And for Martinengo it may have provided the reason to move on from Alexandria: this time to Turkey, home of the lute.

He would take with him red brasilwood from the East Indies— a dye-wood that was so valued that when a few years later the Portuguese found it in the New World, they would name a country after it. Ironically another dye from the Americas would cast it out of favor, and when cochineal had taken over from all the other organic reds, brasilwood was worth next to nothing; it could sometimes just be found rotting at the docks. It was in this cheapened state that violin bow-makers discovered it in the eighteenth century, and pernambucco—the finest brasil from Brazil, so strong it almost resembles iron—became the favored material for good bows. One celebrated English bow-maker called James Tubbs was known for his extraordinary chocolate-colored pernambucco. Some said he stained it with stale urine, although when I tried this—a process I cannot recommend—it made the wood more treacly than chocolatey: a slight shade darker than in its natural state and just a little shinier. Perhaps it made a difference that I hadn’t consumed a bottle of whiskey that day. Tubbs was known to have enjoyed his drink.

Martinengo would have found a ship heading north, bisecting the Mediterranean and then taking him along the Turkish coast. And on the way he would have wanted to stop on the island of Chios, almost within hailing distance of the mainland. For Chios was the home of one of the most important items in a stringed instrument-maker’s workbox: a lemon-colored resin that is so chewy it is called “mastic.” And which was then so highly priced it would have made anyone gulp. But if, arriving at the port, our travelling lute-maker had asked to see the famous

Pistacia lentiscus

trees for himself, then people in town would have smiled sadly and shaken their heads. And if he had found someone to translate then he would have heard a story that would have reminded him of his own troubles as a man punished for his faith.

The legend tells of how a Roman soldier called Isidore landed there one day in 250 A.D. He was a Christian, and he refused to make sacrifices to the Roman gods. The Governor thought carefully about this odd man, and decided he would first be whipped and then burned alive for his insolence. But when the Roman soldiers tied Isidore to a stake, the flames played over him but they did not burn his flesh. So they tied him to a horse and dragged him over the rocks on the south side of the island; and just in case that hadn’t killed him, they cut off his head.

At that moment, the story goes, every tree on the south side of the island wept for the martyr, and their tears hardened, and became mastic. And it turned out to be not only an excellent golden varnish for paintings and for musical instruments, but also a natural chewing gum. It was, and still is, collected every summer by making cuts in the trunks of the little mastic trees. After a few hours the trees weep for St. Isidore, and the resin falls onto the carefully cleaned ground.

Throughout the Middle Ages, Genoese, Venetians and Pisans fought for possession of the island and of its prized crop. And each time it was the people of Chios who wept. The Genoese were the cruellest, banning anybody from even touching the trees: sometimes they would kill the offenders; sometimes they would remove their right hands or noses. It was ironic to lose your nose for the sake of a breath freshener.

In the late fifteenth century the island was under Ottoman control and punishments were lighter, but the villagers were still weighed down by oppressive taxation. It was the privilege of the Sultan’s mother to take what she wanted for the royal harem. And she wanted a lot—one year Chios had to supply Constantinople with 3,000 kilos. Either she sold it quietly in the bazaar or there were a lot of women in that harem with bad breath or a chewing-gum addiction. In the 1920s a French traveller, Francesco Perilla, wrote about going to dinner with a family on Chios. He was given a lump of mastic at the end of the meal, and put it in his mouth uncertainly. “The old mistress of the house asked me to give it to her. I was not happy, but I had to do it,” Perilla recalled.

9

“The lady then took the gum and put it in her own mouth, and gravely told me I was doing it wrong.” To the visitor’s horror she then took the chewed piece out of her mouth and “with a gracious gesture offered it back to me, insisting I learn ‘how to do it.’ I tried every excuse I could think of, but in the end it was too hard to say no. So with eyes closed I had to accept it and taste it. I even had to smile.”

It was this chewiness which attracted artists to mastic. Cennino used it for pulling the impurities out of lapis lazuli to make it into blue pigment, and for sticking broken pottery back together. And dissolved in turpentine or alcohol it certainly makes a beautiful varnish for paintings. There is just one problem. It doesn’t mix well with oil. Mastic was one of the main culprits in a major misjudgment of materials in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Just as, a few decades later, the violin world would be full of questions about Stradivari’s varnish, in the 1760s the art world was full of questions about what the Old Masters could have used to get the incredible glow to their work that is so characteristic of works by Rubens or Rembrandt.

In the 1760s there was tremendous excitement about a substance called “megilp,” which was a combination of mastic and linseed oil. It made a beautiful buttery varnish, which was satisfyingly thick to apply and gave an instant mellow golden quality to the painting. Megilp sounds like an ugly made-up word, and probably is. It was also sometimes called “majellup,” which could well be a shortening of “mastic jelly”—and it was certainly a very jelly-like substance. Joshua Reynolds was one of its greatest fans, despite cautions from the Irish artist James Barry, who warned him about people “who are floating about after Magilphs and mysteries.”

10

Separately both mastic and linseed are wonderful on paintings: it is just their jellified marriage which is so dangerous. In 1789 Reynolds was commissioned by Noel Desenfans, the founder of the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, to copy a portrait he had done five years before—of the actress Sarah Siddons as a tragic muse sitting on an armchair so huge it is almost a balcony. He was in a hurry—or perhaps he allowed his dislike of Desenfans to affect his choice of materials—and instead of replicating the twenty or so layers of paint in the original

11

he used megilp to give the impression of thickly applied paint. Probably because of this the later picture—now in the Dulwich Picture Gallery—has darkened prematurely, making her a doubly tragic muse. Nearby is another prime example of the degradation of megilp in Reynolds’s work.

A Girl with a Baby

is thought to be a portrait of the future Lady Hamilton with her first child. “It has, by an interesting irony, degraded disastrously into something that looks like a strikingly modern proto-Renoir,” the curator of the Dulwich Picture Gallery, Ian Dejardin, told me, adding that it was therefore the favorite painting of a “frightening” number of people who leave the Gallery convinced that Reynolds was the first Impressionist, and complaining about the label on the painting, which describes it as “ruinous.”

12

Needless to say, J.M.W. Turner, always so careless of his materials, was also an enthusiastic user of this gloriously sticky-textured but deceitful mixture.

MAD ABOUT MADDER

Leaving the prematurely darkened island of Chios and its sad inhabitants, our traveller would have sailed north to Constantinople—now Istanbul—where he must have thought he had reached the end of his journey. There were already thousands of Sephardic Jews who had arrived before him, setting up shops and synagogues, mourning those who had died but also rejoicing in the chance to start new lives. It wasn’t a promised land, but at least it was a safe one, he may have thought, as he found himself a room in the Jewish quarter, and put out the news that he was available to make instruments on commission. At first he would have concentrated on starting up his business, but I imagine that soon he couldn’t resist exploring the city. Lutes were brought to Spain by the Arabs in the ninth century—the word in English comes from

al-ud

. They had come from Persia, but the Turkish

saz

is a close cousin, and our lute-maker would certainly have been interested in seeing the local instruments.

As he lounged in a sherbet house, sipping sweet drinks and listening to fine Ottoman music, he would have looked around him at the carpets from all over Central Asia, from Armenia to Samarkand—and he would have felt himself floating in a sea of blue and red. The blues were from the indigo plant, and the dark reds were from kermes, but most of the richest orange reds were from a small bush with a pink root, called madder.

Music in Turkey

Martinengo would have liked the effect it had on his instruments—coloring them a fine orange red. He would probably not have wanted his lutes to be too yellow, but would always have given them a darker final coat to make them a warmer orange. Perhaps his color choice would be for the tone, or perhaps it was simply the fashion. But maybe it was because, since 1215, yellow had been a difficult color for the Jews in Europe. In that year Pope Innocent III declared, on behalf of the Fourth Lateran Council, that Jews of both sexes should wear yellow badges, beginning a trend that would end with the Nazis ordering Jews to wear yellow stars as part of their persecution during World War II. By Martinengo’s time these vile laws had been adopted throughout the continent.

13

In Spain and then later in Italy, Martinengo would have been forced to wear such a patch, or perhaps a yellow hat. It would be hard to imagine him liking the color very much.