Collected Essays (8 page)

Authors: Rudy Rucker

And—I told you this book was shaggy—there’s even some mystical physics. Here’s a rant from a guy called The Street Sleeper, telling about his mad-scientist friend The Middle Man.

“Okay, lemme see: There’s a subatomic particle called the IAMton. Physicists, they speculate about it, but the Middle Man knows. He was a cutting-edge hot shot at Stanford. He isolated the IAMton, using a wetware subatomic scanner that re-created the thing in his natural cerebral imaging equipment, and when he did,

it spoke to him

. It spoke to him! Can you fade that? A subatomic particle that tells you,

Yeah! You found me!…

Actually, see, it was

all the IAMtons on the fucking plane

t that spoke to him, in the local macro-octave. Spoke to him through the group of ‘em he had contained in the tokomak field and scanned with the electron microscope interfaced with his wetware. You know?”

Yeah

, I know, John. This is music to my ears, man. This totally makes sense. As Shirley puts it, “Science Fiction, see, is humanity’s way of warning, readying itself; it’s what goes on under the racial Rapid Eye movement.”

One final gem of wisdom. “The universe is alive, but it is not ‘God.’ And…it is not friendly. Nor unfriendly. However, we do not wish to make these distinctions with the American public.” Too true.

Daringly set in the late twenty-first century—well, hey, the twentieth century’s all done!—Bruce Sterling’s

Holy Fire

is about an extremely old woman who gets a radical rejuvenation treatment and becomes a beautiful twenty-year-old. Due to this extreme change in her body she is no longer human in the old sense of the word; she’s post-human. Other SF writers have come up against the task Sterling faces here, how to depict people after technology has made them into superhumans; I would say that no other writer has ever succeeded so well. Here’s one of Sterling’s statements about post-humans: “Machines just flitted through the fabric of the universe like a fit through the brain of God, and in their wake people stopped being people. But people didn’t stop going on.”

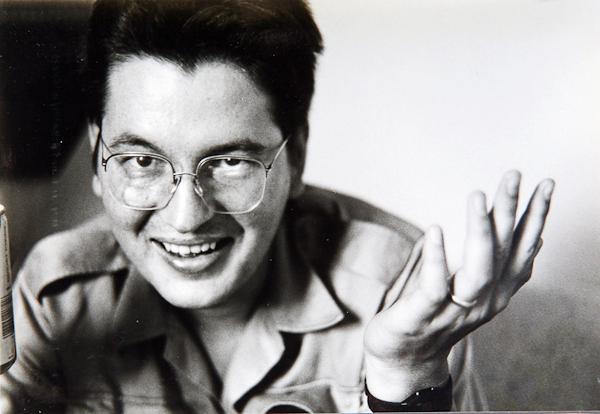

Bruce Sterling in 1983.

In person and in his journalistic writing, Sterling is loud and Texan, but in his novels he is the most thoughtful and civilized of men. In

Holy Fire

he transforms himself into this wide-eyed rejuvenated old lady and takes us on a tour of marvels, a

wanderjahr

in Europe in search of the holy fire of artistic creativity.

She arrived at the airport. The black tarmac was full of glowing airplanes. They had a lovely way of flexing their wings and simply jumping into the chill night air when they wanted to take off. You could see people moving inside the airplanes because the hulls were gossamer. Some people had clicked on their reading lights but a lot of the people onboard were just slouching back into their beanbags and enjoying the night sky through the fuselage.

When science fiction performs so clear and attractive a feat of envisioning the future, its like a blueprint that you feel like working to instantiate.

Instantiate

, by the way, is an object-oriented-computer-programming word that, in Sterling’s hands, means “to turn a software description into a physical object.” Such as a goddess sculpture derived from studies of the attention statistics of eye-tracked men looking at women “…what we got here is basically a pretty good replica of something that a Paleolithic guy might have whittled out of mammoth tusk. You start messing with archetypal forms and this sort of thing turns up just like clockwork.” This pleasing suggestion of cosmic order contains a subtle nod to the notion of a chaotic attractor.

Science fiction sometimes gets humorous effects by extrapolating present-day things into heady overkill. Here’s what espresso machines might evolve into:

The bartender was studying an instruction screen and repairing a minor valve on an enormously ramified tincture set. The tincture set stretched the length of the mahogany bar, weighed four or five tons, and looked as if its refinery products could demolish a city block.

The obverse of this technique is to have future people look back on our current ways of doing things. “That’s antique analog music. There wasn’t much vertical color to the sound back in those days. The instruments were made of wood and animal organs.” Or here’s a 21C person deploring the obsolete habit of reading.

“It’s awful, a terrible habit! In virtuality at least you get to interact! Even with television you at least have to use visual processing centers and parse real dialogue with your ears! Really, reading is so bad for you, it destroys your eyes and hurts your posture and makes you fat.”

Like all the cyberpunks, Sterling loves to write. He can become contagiously intoxicated with the sheer joy of fabulous description, as in this limning of a cyberspace landscape:

“Rising in the horizon-warped virtual distance was a mist-shrouded Chinese crag, a towering digital stalagmite with the subtle monochromatics of sumi-e ink painting. Some spaceless and frankly noneuclidean distance from it, an enormous bubbled structure like a thunderhead, gleaming like veined black marble but conveying a weird impression of glassy gassiness, or maybe it was gassy glassiness…”

Wouldn’t you like to go there? You can, thanks to this lo-res VR device you’re holding, it’s called a printed page…

Sterling is an energetic tinkerer, and he drops in nice little touches everywhere. What looks like a ring on a man’s finger is “a little strip of dark fur. Thick-clustered brown fur rooted in a ring-shaped circlet of [the man’s] flesh.” Two people riding on a train ring for a waiter from the dining-car and here’s the response:

A giant crab came picking its way along the ceiling of the train car. It was made of bone and chitin and peacock feathers and gut and piano wire. It had ten very long multijointed legs and little rubber-ball feet on hooked steel ankles. A serving platter was attached with suckers to the top of its flat freckled carapace…It surveyed them with a circlet of baby blue eyes like a giant clam’s. “Oui monsieur?”

This crab is a purely surreal and Dadaist assemblage, quite worthy of Kurt Schwitters or Max Ernst. The wonder of science fiction is that, with a bit of care, you can paste together just about anything and it will walk and talk and make you smile.

Near the end of the book, the heroine encounters the ultimate art medium.

It was like smart clay. It reacted to her touch with unmistakable enthusiasm…indescribably active, like a poem becoming a jigsaw. The stuff was boiling over with machine intelligence. Somehow more alive than flesh; it grew beneath her questing fingers like a Bach sonata. Matter made virtual. Real dreams.

Such is the stuff that science fiction is made of.

So, okay, those were the three new cyberpunk novels of 1996. Let’s compare and contrast. What are some of the things they have in common other than the use of cyberspace?

One of the main cyberpunk themes is the fusion of humans and machines, and you can certainly find that here. In

Idoru

a man wants to marry a computer program, in

Holy Fire

machine-medicine essentially gives people new bodies. There is less of the machine in

Silicon Embrace

, though there is that remote-controlled guy with the chip in his head.

Another cyberpunk theme is a desire for a mystical union with higher consciousness, this kind of quest being a kind of side-effect of the acid-head ‘60s which all of us went through. Contact with higher intelligence is the key theme of

Silicon Embrace

, though in

Idoru

it is present only obliquely, as part of the idoru’s appeal.

Holy Fire

ends with a thought-provoking pantheistic sequence where a human has actually turned his own

self

into an all pervading Nature god, with “every flower, every caterpillar genetically wired for sound.”

Cyberpunk usually takes a close look at the media; this is an SF tradition that goes pack to Frederic Pohl and Norman Spinrad.

Holy Fire

goes pretty light on the media, but in

Idoru

, the main villain is the media as exemplified by an outfit called Slitscan. “Slitscan was descended from ‘reality’ programming and the network tabloids…, but it resembled them no more than some large, swift bipedal carnivore resembled its sluggish, shallow-dwelling ancestors.” One of the heroines of

Silicon Embrace

is Black Betty, a media terrorist who manages to jam the State’s transmissions.

He watched the videotape, the few seconds of a former President yammering with a good approximation of sincerity in his State of the Union address—and then Black Betty stepping into the shot; stepping her video-persona into the former President’s restricted public space; taking public space back from authority, giving it back to the public, the Public personified by Betty. Tall and lean and smiling from a crystallized inner confidence…she seemed to…stare at the president from within his Personal Space: a rudeness, a solecism become a political statement.

In terms of optimism/pessimism about the future,

Holy Fire

is very optimistic,

Silicon Embrace

very pessimistic, and

Idoru

somewhere in the middle. In terms of political outlook,

Silicon Embrace

is explicitly radical,

Idoru

is apolitical, and

Holy Fire

is—well—Republican? In

Holy Fire

, the world is run by old people, by the gerontocracy, and this is not necessarily presented as a bad thing, it’s simply presented as the reality of that future.

Above and beyond the themes and attitudes, the single common thing about these three books is style. All are hip, all are funny, all are written by real people about the real world around us.

After all the good ink I’ve just given my peers, I can’t resist slipping you a long excerpt of my

Freeware

, which came out a few months after the books discussed here.

So here’s shirtless Willy under the star-spangled Florida sky with eighty pounds of moldie [named Ulam] for his shoes and pants, scuffing across the cracked concrete of the JFK spaceport pad. The great concrete apron was broken up by a widely spaced grid of drainage ditches, and the spaceport buildings were dark. It occurred to Willy that he was very hungry.

There was a roar and blaze in the sky above. The

Selena

was coming down. Close, too close. The nearest ditch was so far he wouldn’t make it in time, Willy thought, but once he started running, Ulam kicked in and superamplified his strides, cushioning on the landing and flexing on the take-offs. They sprinted a quarter mile in under twenty seconds and threw themselves into the coolness of the ditch, lowering down into the funky brackish water. The juddering yellow flame of the great ship’s ion beams reflected off the ripples around them. A hot wind of noise blasted loud and louder; then all was still.

[A crowd of angry locals appears and attacks the ship.]

There was a fusillade of gun-shots and needler blasts, and then the mob surged towards the

Selena

, blazing away at the ship as they advanced.

Their bullets pinged off the titaniplast hull like pebbles off galvanized steel; the needlers’ laser-rays kicked up harmless glow-spots of zzzt. The

Selena

shifted uneasily on her hydraulic tripod legs.

“Her hold bears a rich cargo of moldie-flesh,” came Ulam’s calm, eldritch voice in Willy’s head. “Ten metric tons of chipmold-infected imipolex, surely to be worth a king’s ransom once this substance’s virtues become known. This cargo is why Fern flew the

Selena

here for ISDN. I tell you, the flesher rabble attacks the

Selena

at their own peril. Although the imipolex is highly flammable, it has a low-grade default intelligence and will not hesitate to punish those who would harm it.”

When the first people tried to climb aboard the

Selena

, the ship unexpectedly rose up on her telescoping tripod legs and lumbered away. As the ship slowly lurched along, great gouts of imipolex streamed out of hatches in her bottom. The

Selena

looked like a defecating animal, like a threatened ungainly beast voiding its bowels in flight—like a frightened penguin leaving a splatter trail of krilly shit. Except that the

Selena’s

shit was dividing itself up into big slugs that were crawling away towards the mangroves and ditches as fast as they could hump, which was plenty fast.

Of course someone in the mob quickly figured out that the you could burn the imipolex shit slugs, and a lot of the slugs started going up in crazy flames and oily, unbelievably foul-smelling smoke. The smoke had a strange, disorienting effect; as soon as Willy caught a whiff of it, his ears started buzzing and the objects around him took on a jellied, peyote solidity.