Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness (5 page)

Read Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

As a major port and industrial area, Southampton had been a particular target of the Luftwaffe during the war. At the end of February 1944, when my grandmother was four and a half months pregnant, there was a major raid on the city. “Apparently, every time there was a bomb I jumped,” Mum tells me. “I’m very sensitive to loud noises. It’s why I always look a bit sour at children’s birthday parties in case someone pops a balloon.” Recognizing that air raids didn’t suit the temperament of her fetus and fearing there would be more attacks on the town, my grandmother took the train up to Waternish to wait out the pregnancy.

Telegrams jolted from Skye to Burma to inform my grandfather about the birth of his daughter. “I saw a letter he wrote to his mother from Burma saying that he was very excited about having a little girl,” Mum says. “But of course he didn’t see me until I was over a year old, and when he did finally see me, he picked me up and promptly dropped me on my head.” Mum preempts my wisecrack, “Yes, well a lot of things have been blamed on that little incident.”

But the clearest thing I learned about my grandfather’s war—and about his character—was from an undated letter written to him by one of his Nigerian troops whose obviously warm relationship with my grandfather seemed to exceed the startling, colonial-era salutation that begins:

Dear Master

Will you tell me your present condition? And what news of your family? I hope everyone is 50/50. As for myself, I want to report to you of this: we are no longer at Sandoway but in a township twenty-five miles to Rangoon. We left Sandoway on the 23

rd

of December 1945 to come here. From what I can see, Rangoon is a very big place but I can’t inform you that it is a nice place. Above all, it is a stinking hole, smelly and filthy.

Our current work is boring. We have about 4,000 Japs prisoners staying here with us and our only task is to guard them. That is all the work of 5 Nigeria Battalion. It is not hard work. But upon all that, everywhere else is off limits to us and the worst is there is no prospect of our going home.

So beloved master, that is all the news from the township. I hope you are doing well. Oh! I hope you will be kind enough to see about the picture I asked to send me.

I beg to pen down.

Thanks.

Yours,

John Okongo

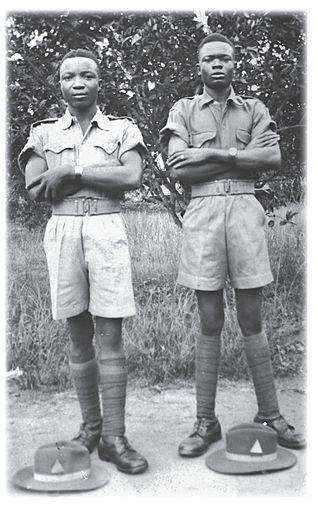

John Okongo, right. Burma, circa 1943.

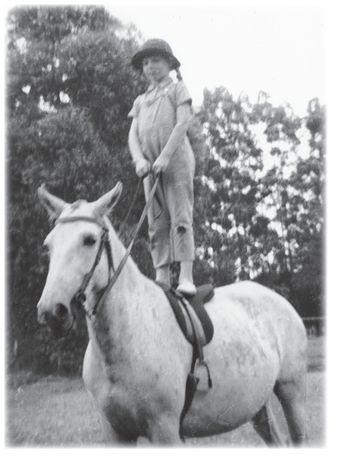

Nicola Huntingford Learns to Ride

Circa 1947–1950

Mum and Nane. Kenya, circa 1954.

I

f she had known then the score and depth of the tragedy that was to come, Mum might have borne the insults of her childhood with more fortitude, but the pathos and the gift of life is that we cannot know which will be our defining heartbreak, or our most victorious joy. And so for a few years from around the time Mum turned three, an accumulation of what she considered truly dreadful events occurred. And because they were the first real insults of her so-far small life, they remain vivid and searing for her even now.

First, her sister, Glennis (Auntie Glug), was born—she had yellow curls, dimples on each cheek and a willful, devious nature. “She managed to have some sort of seizure when she was quite young,” Mum says. “After that, my parents were terrified of smacking her in case she got herself into a state and had another fit. So no matter which of us had been naughty, I always got whacked and Glug got away with smirking at me.”

Then my grandparents left the paradise of the bungalow at the Kaptagat Arms and rented an old army officers’ mess closer to the town of Eldoret. My grandfather knocked rooms around to create a home out of the barracks. “It was very long and narrow,” Mum says, “but my father was very clever with stonework and building. He made false beams in the sitting room to make it look ye olde, and built a wonderful stone fireplace.”

There was no indoor plumbing so hot water was carried into the tub from the kitchen. The choo was a decent trek down to the bottom of the garden, “and often filled with bees and sometimes snakes,” Mum says, “which terrified me and contributed to a lifetime of reluctant bowels.” After dark, each family member was given a chamber pot, “gently steaming away under the bed and rusting the bed springs,” Mum says. “At bedtime, Glug and I had to sit on our pots until we performed. Ages and ages sometimes we had to sit there. Out of sheer boredom we used to have races sitting on our pots, hopping them across the bedroom floor.”

Glug was always getting malaria because she would threaten to have a fit every time anyone tried to make her take a pill. “Doctor Reynolds had to drive out from Eldoret to give her injections,” Mum says. “Glennis would flip herself backward and forward across the room to get away from him and he’d have to try to catch her. One time he made a dive for her and he got his foot stuck in her chamber pot. I remember him skipping around the room in fury. Of course we were both wheezing with laughter, malaria injection quite forgotten.”

Baths were taken under the vicious supervision of a drunken ayah, Cherito, who smacked Mum forcefully and repetitively but without any evident cause, as if she were merely practicing shot put or tennis and Mum’s body was in the way of a particularly powerful swing (Glug, however, escaped the unpredictable violence of even Cherito’s drunken temper, so ingrained was the Legend of Her Seizures and the fear that she’d have another one at the slightest provocation). “My parents would be in the sitting room or on the veranda, quite happily relaxing with some of my mother’s homemade wine while Cherito was swatting me around the bathroom, so they knew nothing of what was happening. And Glug never uttered a peep about it because it was all very good entertainment for her.”

My grandmother made wine out of potatoes, raisins, barley, figs—whatever she could get her hands on. “It was delicious, but she had no control over how strong each batch would be,” Mum says. “It was well known for visitors to leave our house and get terribly confused and end up in the wrong district—and sometimes the wrong country. They’d be on their way to Kitale and end up in Bungoma. Or they’d be expected in Kapsabet but find themselves in Uganda.”

With only the bitterly resented Glug for company, Mum missed Stephen Foster terribly. The donkey, Suk, which my grandmother had bought as a replacement best friend was a big disappointment. In my mother’s telling, he had a willful and devious nature, much like Glug, except with ears and a tail and without the Perfected Art of the Seizure. “Suk was not at all your storybook donkey,” Mum says. “To get anywhere at all, I had to be dragged around by a syce. The donkey sneered at him, ignored me and brayed like a steam engine. I think it was humiliating for all of us.”

And finally, most awful of all, it was decided that it was time for Mum to attend the convent, a school run by Irish nuns about half a mile away from their new home. Every morning, she was put into her uniform, a blue skirt and white shirt with a wide-brimmed black hat, “To keep the African sun off our faces.” She was loaded onto the sulking Suk and hauled to school by the syce. Then the syce and Suk would wait under the eucalyptus trees for three hours until Mum classes were over. After that, she would be put on the donkey, the donkey would be untied and the syce would be dragged from the end of the halter rope as Suk fled for the comforts of home.

As she got older, Mum was allowed to ride Suk over to the school alone. “By then my legs were long enough, and I could just about kick the wretched beast into action.” She tied the donkey up under the eucalyptus tree and went in to lessons. “Nicola is a disruptive influence in the class,” her school report read. Mum found learning difficult. She showed early promise as an artist, but the nuns didn’t care about art. Numbers made no sense to her at all, and even words were hard for her to grasp, “Our parents read to us every night, Rudyard Kipling, Ernest Thompson Seton, that kind of thing. I adored stories and books, but I struggled with the nuns and their dreary lessons and it took me ages to learn how to read.”

Instead, she entertained herself by trying to coax one of the many cats that hunted in the school drains to come and sit on her lap. If the cat couldn’t be persuaded into the classroom, Mum jumped out of the window after it. And then, since she was not Catholic—“Anglican, of course!”—and therefore could not be made to kneel in the chapel with the other recalcitrant girls fingering their way through endless rosaries, she would be banished to sit under the eucalyptus trees, which she found agreeable enough. She spent her time drawing in the dirt, peeling the bark off the trees, lolling on Suk’s back, staring up into the leaves pulsing against the sun-stained sky and daydreaming until she calculated it was time to go home. Then she untethered the donkey, grasped her arms around his neck and galloped back for tea.

MUM HAS TO GO BACK sixty years to recall the convent and those nuns, but the bits she pulls up from her memory are bright and sharp, kept polished and immediate by a deep and abiding hatred for the place and for the women who ran it. “Sister Bede used to smack our hands with a ruler so hard the ruler often broke. Sister Philip caned us around the back of the legs until she raised welts.” Mum pauses and her eyes go pale. “They smacked me and punished me and banished me, but it just made me more difficult and defiant and determined not to learn.”

One day the nuns blocked all the drains and gassed the school’s stray cats. “Dozens of cats, corpses everywhere,” Mum remembers. “Their poor little poisoned bodies piled up in heaps, swelling in the sun. If you’d put them tip to tail, they would have gone all the way around the school buildings. And the next day we were overcome by the awful stench of burned fur and flesh when the gardeners doused them in fuel and set fire to them. It was too awful. Too, too wicked.”

Mum considers that the nuns became bloodless and heartless because they weren’t allowed to drink and gamble or have any fun, while the priests were allowed to get drunk and bet on horses at the racetrack. “The nuns were supposed to be above all earthly desires and temptations. They weren’t even allowed to be observed eating. They had a furtive dining room at the back of school where they had to eat behind closed doors and closed curtains. No one could ever see them do anything biological. We schoolchildren had an ongoing argument about whether or not nuns really did eat, and if they did, what happened at the other end. Of course, I think they took all their irritation and disappointments and repressed urges out on us.”

After four years at the school, Mum had a fairly good idea that hell involved nuns and convents, so when an inferno worthy of Hades exploded in the blue gum trees near the school, it was not a surprise, but what

was

a shock was that Suk, as usual, was tethered to one of the trees. It was toward the end of the long dry season; the wind had been red all day with dust blown in from Uganda and settling on everything like powdered blood, the sun blistered out of a high, clear sky. Finally at noon that day, the volatile eucalyptus sap caught fire. From her desk in the classroom, Mum saw the flames out of the corner of her eye and was in a full run toward her donkey before her mind fully understood what her body already knew. But before she could run into the flames, she was caught fast in the powerful grip of Sister Philip’s manly hands.

“I could feel the explosion of those trees in the pit of my stomach,” Mum says. One tree after the other blew up, each flaring limb and trunk bringing the fire closer and closer to Suk. The little donkey tugged and strained at his halter, but the rope held fast. Mum watched helplessly as a wall of fire consumed the tree under which Suk fretted. The donkey disappeared from sight and his screams were lost in the roar of the oily flames. Mum felt the world contract into the denial that comes with tragedy, the refusal to believe that time cannot be stopped, reversed, undone. “No! No! No!”

Then, out of the flames, singed and braying in pain and fright, the donkey staggered, flesh and fur hanging from his back in charred strips. His halter rope had burned through, and was dangling under his chin. Mum tried to squirm out of Sister Philip’s grip, but the woman’s hands only squeezed tighter.

“Let me go!” Mum cried. She twisted and kicked in the vice of Sister Philip’s grasp, but she could not get free. Then she swiveled her head and looked up at the nun and what she saw chilled her then, and stayed with her forever. “Sister Philip was staring at Suk with furious, cold blue eyes under her bushy ginger eyebrows. I knew then that she had put the Evil Eye on him. She’d started that fire.” Mum nods. “I’ve never had any doubt about it. That bloody nun was a witch.”

My grandmother nursed the donkey back to health with liquid paraffin and May & Baker antibiotic powders, but Suk sensibly refused to go anywhere near the school again. Anyway, he remained completely bald over much of his body, “and you can’t ride a bald donkey.” So for some months Mum was forced to walk to school every morning alone, and when she was sent to sit under the scorched eucalyptus trees, she could no longer lounge on the back of her donkey, staring up at the sky. Belatedly, and to her heartbroken surprise, she found she missed Suk’s obstinate, scheming companionship.

THE SHORT NOVEMBER RAINS CAME, followed by the startled, green days of Christmas. Then the longer rains arrived in March and stayed all through May. Walking to school, Mum collected clogs of mud on the bottom of her shoes. The roads turned fluid and my grandfather had to put chains on his tires to drive anywhere. Then May dried into June and the long dry season started again.

“What you saw first,” Mum says of the occasional, almost mystical arrival of the Somali horsemen, “was a pillar of dust coming from the edge of the plateau.” And by nightfall they were in Eldoret and you could hear the bells around the necks of the lead mares and the men shouting to one another in their exotic desert tongue. Their little campfires lit orange out of the grasslands, and the shapes of horses milling and men in silhouette ghosted the vlei.

Hundreds of Somali ponies had arrived, worn muscular and sinewy having trekked almost the entire breadth of Kenya from the drylands of Somalia. “Only the fittest, sturdiest animals survived that long, difficult journey,” Mum says. The herdsmen—every bit as tough as the animals they had come to sell—were lean and secretive behind their white wrappings of desert garb, dry and folded as moths.

Within the week, the horses were all taken over to Betty Webster’s place, one of Eldoret’s riding teachers. “She set up benches and a thatched shelter at her riding arena and there was an auction of all these fabulous ponies which, of course, I had to miss because of school. But my mother and father went. They were very keen on Somali ponies and they decided that a pony of my own was exactly what I needed to take my mind off what had happened to poor Suk.”

Back in the early 1930s, before Thoroughbreds made it to East Africa, my grandfather had won the Kenya Gold Cup on his Somali pony, Billy. “Not much to look at,” Mum says. “They tended to be ewe necked, goose rumped, straight in the shoulder, and they were tiny—average height, about thirteen point two hands—but the main thing is they had endurance and they could run like the wind if they felt like it.”

At the auction, my grandmother was taken with a sturdy gray gelding. She thought he had a nice direct way of looking at a person. A herdsman with sun-baked eyes and a lip full of khat agreed to let her ride the pony before she bought it. For the first and only time in his life, the creature behaved like an angel. He allowed his feet and teeth to be checked, he didn’t kick or bite, he willingly jumped every obstacle put in his path, he turned and halted nicely. My grandmother paid the herdsman a handsome sum and she named the pony Nane, Kiswahili for the large eight branded on his rump.