Classic Christmas Stories (17 page)

Read Classic Christmas Stories Online

Authors: Frank Galgay

Christmas has gone long ago. Already we have heard ominous groaning

of the heavy ice along the land-wash, warning us that the open sea is getting

nearer, and that soon our icy fetters will be broken. The toys and trinkets

from the poor spruce tree have already lost most of their pleasure-giving

power. Must it not always be so, at last, with the things we are apt to call

“valuables.”

Clem has gone to his home again. He is able to run and walk like the

merry lad he is. For not only his life, but his limb also, has been saved to him.

And we have learnt once more that the real joy of Christmas comes of those

small opportunities for giving to others—faint efforts to re-echo, however

faintly, the love this feast commemorates. There is no cant in saying, “It is

more blessed to give than to receive.”

by Hans Rollmann

T

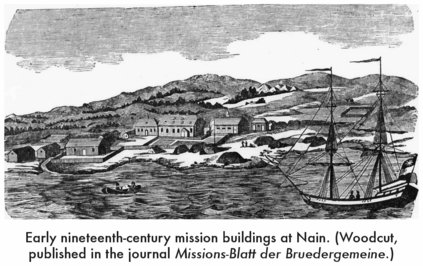

HE TEMPERATURE HAS FALLEN to thirty-six below and the

wind howls along the palisades, yet inside the sturdy wooden

building fourteen Moravians thank their Lord for the warmth of

Christmas. The little band—six Germans, four Danes, and four Britons,

including three women—is celebrating its first Christmas Eve at Nain,

having arrived in the bay in August of 1771. In haste they built their mission house. One Inuit, Manuina, settled near the Europeans with his two

wives and three children, but the family is presently in Aupaluktuk with

his brother-in-law in search of whales.

Alternating between German and English, the Moravians sing

familiar Christmas hymns, but also remember Christ’s crucifixion,

the two focal points of their piety. Jens Haven, the Danish carpenter,

sings with fervour. Once a missionary in Greenland, he has kept alive

the idea of a Labrador mission after a first effort in 1752 by Johann

Christian Erhardt failed. Now he has become the driving force behind

the settlement in Nain after three previous explorations. Next to him

stands his wife, Mary Butterworth, a good-natured Yorkshire woman

who joined the Moravians at Fulneck. She married “little Jens, ” as he is

affectionately known among the Inuit, in May, only a month before their

departure for Labrador. Tonight, the Christmas story with the child in

the manger resonates with a special meaning for this Mary in Labrador.

While she sings, she feels the movement of her first child within her.

John Benjamin will be born in February, 1772, and will later follow in his

parents’ footsteps as a missionary.

Superintendent Christoph Brasen, a Danish barber surgeon married

to an Alsatian wife, records this first Christmas Eve service in the Nain

diary. “We offered Him our poor and sinful hearts including life and soul, ”

he writes, “to serve him willingly and stand at his command, whatever

he wants to use us for in this rough and cold land.” He only regrets that

Manuina and his family cannot be with them. He knows that song and

celebration are much more effective in communicating the Moravian

religious message than their theology or doctrine. He also knows that

Manuina loves to sing about the Christ child.

While they now sing in unison with their brothers and sisters, in three

years’ time the superintendent and Gottfried Lehmann, a weaver from

Saxony, will no longer be with their brethren. The two will perish when

their sloop founders north of Nain on an exploration journey to establish

a northern missionary outpost, the future Okak. Okak in turn will be

devastated by the Spanish influenza epidemic in 1918 and disappear as

a community. Only the rhubarb is still a silent witness to the Moravian

presence.

On Christmas Day, Larsen Drachardt preaches a sermon about

the little child in the manger who was also God. In the sermon, the

sixty-year-old theologian revisits his childhood days in Denmark and

reflects perhaps about his later life as a journey in grace, especially the

Lutheran missionary service in Greenland that changed his life forever.

In Greenland, Drachardt learned the language of the Inuit during his

twelve-year stay and eventually became a Moravian. After a mystical

experience of Christ’s presence in Greenland, he later joined Jens Haven

on two of his exploratory journeys to Labrador. In 1765, he interpreted

for Governor Palliser at Chateau Bay, becoming a bridge between the

Europeans and Inuit.

The third day of Christmas is celebrated with joy and solemnity. The

temperature has now fallen to forty degrees below zero. At dusk when

the Europeans sit together, reminiscing and reading, they are suddenly

startled by a loud scream from outside. The dogs start barking furiously.

When they run to see what has disrupted the quiet of their holiday evening,

they discover Manuina, their Inuit neighbour. Fearing the dogs that run in

front of the palisades, he wields a large knife. He is alone, but his wives are

not far behind. He has merely run ahead of them to arrive before it is too

dark to be recognized outside. An hour later, the two women follow. Since

it is so cold and the family has not lived in their dwelling near the station

for some time, the Moravians prepare them sleeping quarters in the little

hall of the mission building. The Inuit also take part in the missionaries’

evening service as well as in their morning blessing of 28 December. A

deep bond unites European and Inuit during this first Christmas season.

“We all feel a special love for the man and his family, ” Brasen writes in the

communal diary, “and they definitely also trust us.”

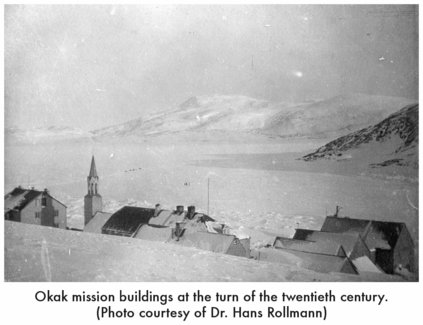

The Okak Moravians celebrate their first Christmas Eve in 1776 with

a so-called love feast, a simple shared meal amidst singing and prayers,

restoring an early Christian practice adopted also by the Methodists, who

celebrate love feasts in the 1770s in Conception Bay. Jens Haven, who is

part of the first Christmas at Okak, writes in the diary that they keep a

night watch and “pray to the child in the manger in front of his creche.”

Similar religious celebrations continue the next day, Christmas.

The Okak diary records the mixed feelings of solidarity and isolation

of those labouring in such a remote location. The nearby Inuit visitors

are also told the good news of Christmas, a message to be repeated the

following days at nearby Uvibak and Kivertlok by Haven and Johann

Ludwig Beck, a missionary with Greenland experience who joined the

Moravians in Labrador in 1773.

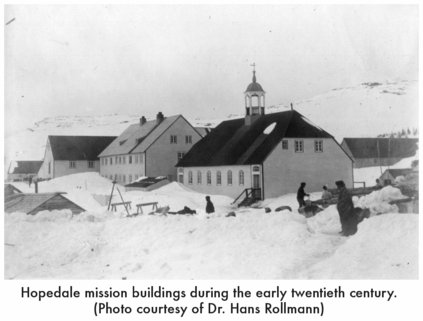

Hopedale celebrates its first Christmas in 1782. At this station south of

Nain, the children are the centre of the Christmas Eve festivities. Thirty-three of them meet and are read the story of Jesus’ birth. Each child is

given some bread as a gift. Afterwards they are also shown a nativity scene

and a representation of the crucifixion. The children and mothers are

particularly drawn to these artistic images. Later, the Europeans celebrate

a love feast and pray in front of the nativity scene and—according to

Haven, their chronicler—welcome the dear child and ask him to come

into their midst and remain with them. Christmas Day is spent in praise

of the incarnation and with thanks that Jesus has come as their brother.

On 26 December, the good news story of Christmas is recounted to

the Inuit, but here the diary reveals the difficulties of the entire missionary

enterprise. The drama in the encounter of the two cultures—European

and Aboriginal—can still be sensed in the casual remark of Jens Haven,

who feels that communicating the message of the saviour’s birth “is not

as easy to make clear as one would wish.”

Today Moravians retain their distinctive Christmas celebrations and

remain a mission-oriented church, although Labrador Moravians are now

administratively on their own. Today Moravians also think of missions

somewhat differently, emphasizing the need to change society not from

without but from within. In the words of a Moravian from Africa during

a recent conference on missions: “The example of the Apostle Paul who

became ‘to the Jews a Jew and to the Greeks a Greek, ’ deserves repeating

more now than ever before.”

by Hans Rollmann

O

N CHRISTMAS DAY OF 1866 Thomas Merrifield was

fighting for his life.

Already up to his knees in what the settlers called “slob”

and the Inuit “sikuak, ” he continued to sink. The events of his forty-four

years ran in rapid succession before his eyes: his youth and upbringing

in Devon and, thereafter, his hard life on the north coast of Labrador.

Elizabeth, his wife, had come to share with him the privations and simple

joys of a settler in the bay.

She and their daughter, Harriet Elizabeth, had gone ahead of him

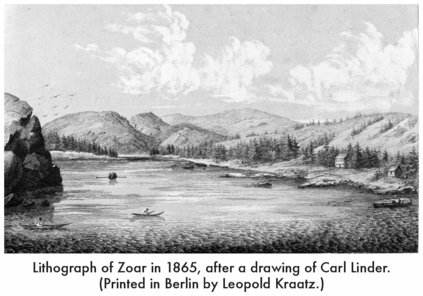

by sled to Zoar, the new spiritual and social centre for Inuit and settlers

living between Nain and Hopedale. Not even these loved ones could

hear his anguish. Thomas Merrifield was all by himself. The man after

whom a bay and a mountain would be named was only a solitary speck

on snowshoes, sinking in a partially frozen Tasiuyak Bay.

Or was there somebody, after all, who had listened to Merrifield’s

anguished prayer? For just as he was about to resign himself to his fate—

perhaps thinking for a moment that he should have accepted the invitation

of his former drinking companions to join them for a party instead of

spending Christmas with the Moravians at Zoar—just then he felt something

firm under his feet. His snowshoes caught and were able to sustain him, and

with one more effort he reached the safety of more compact snow.

Later that day, he saw the lights of the mission house. Exhausted,

frozen, yet glad of his salvation on a partially frozen bay, Merrifield

stumbled into the house, where an anxious wife and daughter were

waiting for him.

This true story happened in 1866 to the man after whom Merrifield

Bay near Davis Inlet is named. The Moravians, a mission-minded

Protestant Church, after establishing themselves on Labrador’s north

coast in Nain (1771), Okak (1776), Hopedale (1782), and Hebron (1830),

had answered a call to accommodate Inuit and settlers living between

Nain and Hopedale. Named after the biblical village of Zoar ( “Little”),

into which Lot and his family fled for refuge when Sodom and Gomorrah

were being destroyed (Genesis 19), the mission station was planned for

spiritual and economic reasons: spiritual, to share and sustain the faith

of Inuit and settlers living between Nain and Hopedale; and economic,

to encourage Inuit and settlers to trade their fish and pelts with the

Moravians instead of with Hunt & Henley or the Hudson’s Bay Company,

fierce competitors of the Moravian trade, or even with the Newfoundland

schooners now showing up annually on the coast.

Eventually, economic reasons closed the store when the indebtedness

of those trading with the missionaries at Zoar had reached unmanageable

amounts and their numbers decreased. The original building of this

extension of Nain and Hopedale, nestled in a picturesque bay, was

constructed in 1865. In the following year, Friedrich Elsner and family as

well as a single Danish brother, Peder Dam, moved into the new premises.

Inuit eventually settled nearby, but the congregation remained small.

They erected a log house and a somewhat larger building complex that

served as store and church, and—as in all other Moravian settlements

except Killinek—planted an elaborate garden.

In the winter of their first year at Zoar, the Moravians also started

a school for children, as they had done in other places, since education

and schools ranked closely after worship and missions in their value

system. A trained Inuit schoolteacher, Thomas, who had accompanied

the missionaries from Nain, served as instructor.

The missionaries were, however, surprised and gratified by the great

responsiveness and support of the settler families living in the area, who

considered the new station their home.

Next to the Inuit schoolteacher, Thomas, and the new chapel servant,

Nathan, two settler families stood out in the congregation. Amos

Voisey, who had once worked for a Moravian competitor, had joined

the congregation at Zoar with his extended family, while the Merrifield

family, living at Merrifield Bay, also came to consider it their spiritual

home. Especially in those two families the missionaries saw the Spirit

moving.

The English settler Amos Voisey of Voisey’s Bay fame, originally a

member of the church in Hopedale, sought spiritual counsel from the

Zoar missionaries and later also entered into a business relationship with

them, as did his son George, who was a member of the congregation.

One evening, the spiritually troubled Amos had unburdened himself

to missionary Peder Dam, asking him earnestly whether his sins could be

forgiven. Dam answered that the resurrection of Jesus was witness that all

sins had been borne by Christ, even those of Amos Voisey. For Voisey, a

religious backslider, these words initiated a spiritual breakthrough.

“Waking as from a dream, ” Dam wrote of this encounter, Voisey

“exclaimed, with tears in his eyes, half-loud: ‘This is it! This is it! I

was missing the resurrected Christ.’ Upon that he went home, and I

recommended him to the faithful care of the Holy Spirit. Now he goes

gladly about his way and is a friendly, very relaxed and happy man.”

Changed lives in the Merrifield family also encouraged the

missionaries at Zoar. Thomas’s wife, Elizabeth, became the first convert

of the Zoar church. The daughter of James Lane and an Inuit woman by

the name of Clara, Elizabeth lived a life without religious commitment

until she met the Moravians at Zoar and became the first person baptized

at the new station. Later, her adult daughter, Harriet, and her husband

would follow her into membership.

Also at Zoar, the last unconverted Inuit south of Nain, Itorsoak, the

forty-three-year-old son of Pualo, was baptized in 1868 and received the

Christian name of Jeremias. As the congregation, swollen to seventy-four

people, crowded into the Zoar mission house on that Christmas Day in

1866, the missionaries tell us of an especially great religious intimacy and

fellowship that was experienced by the assembled congregation.

“We felt, ” the diarist of Zoar writes, “so real the blessing of His birth

in the stable. Our visitors seemed to feel the same. Brother Merrifield

said: ‘How delectable is such a celebration of the birth of our saviour! It is

the first time in my life that I celebrate it in such a way. And I hope I will

never return to my old ways.’”

The weather worsened that Christmas Day so that all visitors had

to remain at Zoar for longer than they had planned. But there were no

complaints, as each enjoyed the company of the others and their Christian

fellowship.