Class (15 page)

My thrill at Oxford was that I met the aristocracy, but for Angus Wilson, it was rubbing shoulders, and goodness knows what else, with the working classes:

‘There had of course, been my London sexual encounters, many of them with cockney working-class young men, but the glory of Merton was I found myself meeting for the first time working-class men who came from the Midlands and the North.’

This, and the earlier quotation from John Betjeman, comes from

My Oxford.

Recently published together with

My Cambridge

, this is a book in which well known people each wrote a chapter describing their experiences as undergraduates. What is remarkable—apart from the high standard of writing—is what incredibly class-conscious documents they are. One feels that the authors wrote with an honesty about their origins they would never have displayed if they hadn’t been so successful.

Eleanor Bron, for example, found herself mixing with an upper-middle-class intellectual élite, which made her unable to communicate with her own family (working-class Jewish) when she went home:

‘I was too clever; like Alice I had grown and couldn’t fit in the door anymore.’

Alan Coren arrived at Oxford at the beginning of the ‘Flat-“a”-working-class-is-beautiful era’ and capitalized on his own self-admittedly humble origins:

‘I had a great success with

Isis

on the strength of a donkey jacket from a second-hand shop, an accent that went with it, cracking knuckles, narrowing eyes to slits and spitting out pips with no concern for target. This was how I became an authentic working-class voice, and sold many stories to a succession of gentlemanly editors.

‘This was in the post-Angry days, when people referred to themselves as “one”, blushed and started referring to themselves as “you”, and tall willowy lads with inbred conks and hyphens stood before mirrors abbreviating their drawl, dropping aitches, and justifying a family that went back to the fourteenth century by saying they were all solidly behind Wat Tyler.’

Piers Paul Reid, upper-middle-class and second generation intellectual, arrived a few years later at Cambridge when the egalitarian movement had reached its height and the middle classes actually sought out working-class company. One of his friends recounted with a frisson of delight that there was actually a miner’s son with rooms in the same building. Alas, in Piers Paul Reid’s college ‘There was only

one

boy who lived in a council flat. But he could grasp logic and metaphysics, and at the same time amass a variety of scholarships and grants by the judicious exploitation of his background. He avoided paying bills and was treated leniently because colleges were as eager to cultivate those proletarian seedlings as were American colleagues to cultivate black students.’

Having ferociously despised Etonians at the Pitt Club, Piers Paul Reid then reluctantly discovered that they were rather nice. Finally he went to a May Ball at St Johns, ‘where there were girls in long dresses, and men in hired white tie and tails, not Etonians, instead bright guys from the grammar schools, and minor public schools, intoxicated by the mirage of success’—Jen Teales, in fact, trying to maintain some standard of gracious living in the face of rampant egalitarianism.

By 1968 the ‘working-class-is-beautiful’ movement was coming to a head with student power joining forces with militant workers (a far cry from the undergraduates who rallied in 1926 to break the General Strike). But from then on things began to change. The austerity years arrived and, instead of power, undergraduates started worrying about survival, about fast-diminishing grants and getting a job when one went down. The possibility of actually joining the working classes in the dole queue suddenly made them seem less attractive. People no longer wanted to get a job helping people or burned to do something in the Third World. Instead, they wanted to amass a fortune in the Middle East.

‘Apart from medics and Indians,’ said one Oxford undergraduate, ‘all anyone wants to do when they leave here is to make a fast buck.’

According to

The Sunday Telegraph,

in recent years the main scramble has been into those twin middle-class havens of indispensability—law and accountancy. The proportion has doubled in the last two years. Soon, no doubt, the market will be flooded and there’ll be hundreds of out-of-work accountants working as waiters. (At least they’ll be better at adding up the bill than out-of-work actresses.)

‘A few years ago,’ confirmed a don, ‘I spent my time convincing people that Marx hadn’t said the last word on everything. Now I spend the same amount of time persuading them everything he said wasn’t complete rubbish.’

The universities, in fact, have become bourgeois. How then have the classes re-aligned?

‘One does generally mix with people of one’s own type (i.e. class),’ said an upper-middle-class undergraduate from Oriel, ‘though this is by no means a conscious or rigid principle—but it does seem that many comprehensive and grammar school types are not very interesting people, or at least seem to have less in common with one because of their background.’

‘At teacher training college,’ said a working-class boy, ‘we found our own level and stuck together. Particularly in evidence was a stuck-up group we called “the semis” (lower-middle, Jen Teale again) who got engaged in the first year. All they talked about was houses and cars. The only aggro I got was at Christmas dinner when the principal told me to leave the table for not wearing a tie.’

‘You don’t notice people’s backgrounds,’ said an old Harrovian now at Reading, ‘until someone almost beats you up for asking his name. Yobbos are less tolerant of having the piss taken out of them, and tend to overreact, which public school boys don’t understand. When they get a bit of confidence, yobbos who’ve been up for three or four years take a delight in mimicking one’s accent, which can get very offensive.

‘I went out with a grammar school girl,’ he went on ‘and I shared a flat with a boy from a comprehensive school. Apart from his talking about “lounge”, “settee” and “toilet”, we got on very well, although communal eating was a problem. He wanted to eat early, I wanted to eat late. Dinner in hall was a sore point—between 5.30 and 6.30, but I expect that’s for economic reasons. You get so hungry you have to buy something from the bar to eat later.

‘One thing I did learn was that, if I got drunk, I broke up public school boys’ rooms, and they always broke up mine. It’s much easier to break up rooms of those who you know will take it well. Public school boys don’t seem to mind so much about their possessions or other people’s whereas yobbos do seem to care.’

Today at university the classes seem principally to be re-aligning into the upper- and middle-class guilty, the lower-middle materialistic and working-class cross. And although the middle and upper classes are no longer assiduously courting the working classes, a terrible inverted snobbery has now developed. ‘The young,’ said Anne Thwaite in the Introduction to

My Oxford,

‘tend to avoid Oxford and Cambridge for egalitarian reasons, opting for Sussex, York or East Anglia, as somehow being more mysteriously like real life.’ There was a don at a redbrick university who said he would never dare write a book about the middle classes because he couldn’t possibly justify it to his students.

Nicholas Monson overheard two sociology students having a passionate row over which of them was more working class: ‘One said his father was a miner in Darlington, while the other countered victoriously that, although his father had worked as an insurance clerk, his grandfather had gone on the Jarrow march. The first refused to concede his superior origins because his opponent’s origins had been partially diluted by the capitalist occupation of his

petit bourgeois

father.

‘They clearly needed the assistance of a recognized authority,’ added Nicholas Monson dryly. ‘Perhaps next year we might see the first edition of

Burke’s Peasantry

.’

Even upper-middle-class at Oxford are worried about their image at the moment. They were perfectly beastly to Princess Anne, priestess of the flat ‘a’, when she visited the Union recently. Gay libbers, women’s libbers and general lefties jostled her and shouted four-letter words outside; inside there was intense heckling and a ghastly audience participation exercises in which everyone had to turn to the person on their right and ‘say in your poshest voice “Hullo dahling”.’

Then

The Cherwell

also runs a competition for the pushiest freshman: ‘He who hacks most people in the most disgusting way in his first term.’ A hack is someone who solicits, pesters, toadies, and generally social climbs, in order to cunningly gain an advantage over others, by boring the pants off people in the Union bar, and then relying on their vote. Rather like Eton running an Upper-Class Twit of the Year contest.

Oxford, in some way, is more a target for egalitarianism than Cambridge. As Eleanor Bron pointed out, ‘At Oxford all acquire a veneer of upper-middle-classiness, while at Cambridge, home of scientists and fact rather than opinions, they simmer down to a vague middle and lower-middleness.’ Oxford’s trouble is that, despite efforts to the contrary, they get more and more élitist. ‘In the old days considerable gifts of spirit and intellect were needed to counter severe economic disadvantage,’ said J.I.M. Stewart, ‘but now most people are hard up, no college is noticeably cluttered up with hopelessly thick or incorrigibly idle youths from privileged homes.’

Ironically, although they may no longer be idle and overprivileged, 50 per cent are still from fee-paying schools because Oxford can’t get enough candidates from the state system.

‘Chaps from comprehensives simply aren’t up to it,’ said one don. ‘You look for promise not achievement, then you say, “Dash it, would they ever pass prelims if we let them in?” and so in the end you say, “No, go somewhere else where they’ll feed you compulsive lectures”.’

An interesting statistic is that women graduates as a whole tend to be socially superior to men. Most of them come from Social Class I in the Census which means they are daughters of lawyers, doctors, engineers and accountants. This is probably because the upper-middles are the least male chauvinist of all the classes and therefore, unlike the aristocracy, the lower-middles and the working classes aren’t so resistant to women being educated.

The exception to the upper-class rule is, of course, the Pakenham family, who were all expected to get a first. Evidently when Lady Antonia broke the terrible news to Lord Longford that she’d only got a second, there was a long pause; then he said with characteristic charity, ‘Never mind, darling, I expect you’ll get married.’

According to the Old Harrovian at Reading University, ‘A lot of girls go to university to find a husband, although they would be livid to be told that. I fancied a girl who’d been to grammar school. Very clever—three As at A level—who I started to go out with, but she would only allow me to kiss her, saying if I wanted more I’d have to promise more. Well I ran away like a coward, and in my absence a creepy sort of chap stepped in and having promised all, i.e. an engagement which he’ll never keep, is enjoying her favours.’

The undergraduate at Oriel said that, in almost every case, people take sexual partners from the same class. ‘If they’re socially mis-matched there’s usually not enough common ground to keep a conversation going.’

‘Nice girls,’ wrote Antonia Fraser about Oxford in the fifties, ‘never accepted invitations from unknown undergraduates in the libraries, and lived in mortal fear of being seen out with men in college scarves and blazers with badges on,’ and adds, with commendable hindsight now that she’s living with the far from patrician Harold Pinter, ‘no doubt missing the company of almost every interesting man in Oxford.’

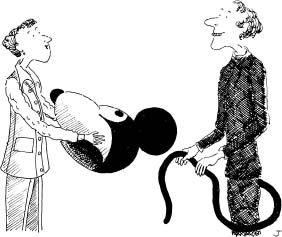

‘But Wayne, dear—are you

sure

that’s the sort of tails they meant?’

Dive Definitely-Disgusting, however, is so proud of getting to a university that he wants to advertise the fact by wearing college scarves and blazers with badges, at the same time dissociating himself from the plebs in the street, showing that he’s ‘ge-own’, not ‘te-own’.

In the conventional late ’seventies sales of college scarves went up sevenfold in Oxford and sales of blazers with badges fourfold. This may be because the campus look is fashionable, because in a time of uncertainty people search for identity, or because they’re all being bought by Zacharias Upward trying desperately to look like a yobbo.