Clash of the Sky Galleons (18 page)

Most sky ship stone pilots kept themselves to themselves, seldom spoke and devoted almost all their attention to the notoriously difficult business of tending the flight-rocks in their care. But even the most dedicated pilots occasionally took off their conical hoods and set foot on the ground. The

Galerider’s

stone pilot was different. A constant figure on the flight-rock platform - at all times and in all weathers - the Stone

Pilot never took off the conical hood, apron and gauntlets of the profession, or uttered so much as a single word.

As mysterious in her own way as the great flight-rock she tended, the secret of the Stone Pilot’s identity was known only to the

Galerider’s

crew, the brave young sky pirate who had rescued her and his friend Maris.

‘Down a tad, Stone Pilot!’ The sound of Quint’s voice, calling from the helm, broke into the Stone Pilot’s thoughts.

Laying the brush and the cooling-rod aside, she jumped to her feet and hurried across to the bellows, which she pumped up and down. The burners flared and glowed brighter, heating the rock just enough to bring it down a little lower in the sky. The Stone Pilot returned to the stool and sat down again. Below, the flight-rock hissed and whistled in its cradle, while above, the sails billowed and tugged at the creaking mast.

Inside the heavy conical hood, it was dark, quiet and safe…

‘Why have you stopped, Sagbutt?’ demanded Filbus Queep.

‘I’ll

tell you when to stop.’

‘Eyes sting,’ the flat-head goblin complained.

‘The mighty Sagbutt, deck-warrior and league-slayer,’ said Filbus scornfully, ‘defeated by a couple of woodonions!’

‘Not a couple,’ Sagbutt grunted. ‘Lots!’

‘Well, I’m sorry about that,’ said Queep, ‘but I

need

lots.’

Sagbutt groaned miserably and wiped his red, streaming eyes on his filthy apron.

‘That’s the thing about woodonion broth,’ Queep said. ‘It requires woodonions. The clue, Sagbutt, is in the name.

Woodonion

broth.’ He glanced up from the triangular chopping board, where three small piles - one of blue-thyme, one of fossweed and one of nibblick -filled each of the corners. ‘And don’t smash them, Sagbutt.

Slice

them! There’s a good fellow …’

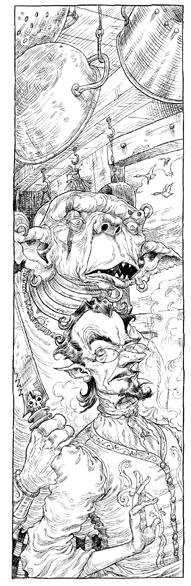

Above their heads, the low beams of the

Galerider’s

galley were festooned with pots, pans, jugs and cooking utensils of every description: ladles, whisks, sieves, hanging-scales, wooden spoons and spatulas; rolling-pins, mallets, hatchets and heavy chopping-knives. In the corner, by the low cabin door, a small stove glowed purple, the buoyant lufwood inside jumping and jostling as it burned. Filbus Queep the quartermaster loved the

Galerider’s

galley. He loved its order, its neatness, its precision.

‘A place for everything, Sagbutt, and everything in its place,’ he would say. ‘Just how I like it.’

He especially liked the galley when, as now, it was hot and humid and laden with the delicious fragrances of cooking food; when the air was thick with steam that billowed out from a bubbling cauldron and hovered in clouds just below the low ceiling.

Filbus Queep picked up the boardful of herbs, swivelled round on his heel to the cauldron behind him, and swept them all into the boiling water with the back of his knife. Instantly the fragrance was released from

the aromatic leaves. He added a slurp of winesap, slammed a heavy lid on the cauldron and pushed the whole lot to the back of the stove to simmer. Then he poured a little oil into a pan and put that on the heat at the front instead.

‘Woodonions, Sagbutt,’ he said, without turning round.

The flat-head picked up his own chopping board and, eyes and nose still red and streaming, shuffled to the quartermaster’s side.

‘Excellent, excellent,’ said Queep, tipping the woodonions into the smoking oil. They hissed and spat as they landed, before settling down to a soft sizzle. ‘Smell that, Sagbutt,’ said Filbus Queep, leaning over the pan and breathing in deeply. ‘Doesn’t that make chopping all those woodonions worth it?’

‘Sagbutt like onions raw,’ growled the flat-head, wiping his heavy cutlass on his tunic. ‘Sagbutt like

everything

raw - tilder, hammelhorn, snowbird … ‘Specially snowbird guts - nice and raw and steaming…’

‘Yes, yes,’ said Filbus. He shook his head. ‘Sometimes I don’t know why I bother …’

The quartermaster wiped the steam from his spectacles, placed them back on his nose - and noticed the weapon in the flat-head goblin’s hand. His face darkened.

‘Please, Sagbutt, my dear fellow,’ Filbus said, eyeing the cutlass with evident distaste. ‘Your sword …’

Sagbutt looked at the fearsome blade in his hand, its surface scarred and pitted from battles too numerous to recount.

‘The one you cut off heads with; gut snowbirds with…’ Filbus was frowning furiously. ‘Clean your fingernails with. You didn’t use it to …’

The flat-head goblin smiled broadly to reveal a mouth full of glistening white fangs, and nodded his flat, tattooed head.

‘Yes,’ he laughed, ‘Sagbutt did. Sagbutt used

Skullsplitter

to chop woodonions …’

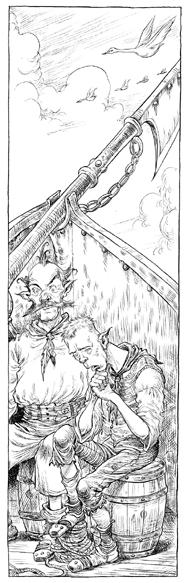

‘And you double it back on itself, like so,’ said Steg Jambles, ‘slip the tide-ring into place. So … Then bend it back the other way, and …’ He tugged the rope firmly, then looked up at Tem and grinned - his teeth, yellowed by years of chewing slipwood bark, gleaming in the afternoon sun. ‘There,’ he announced. ‘One nether-fetter, fully repaired.’

Tem Barkwater nodded, impressed. ‘You made it look so easy,’ he said.

‘It

is

easy,’ said Steg. ‘Once you get the knack.’ He unfastened it, removed the tide-ring and frayed up the end of the rope once more.

‘You

have a try’ he said, handing it over.

Tem took the rope and tried to do exactly what Steg had shown him. The pair of them were sitting on upturned barrels on the fore-deck. With his tongue sticking out of the side of his mouth as he concentrated, Tem smoothed down the rope’s frayed threads, twisting it, turning it, doubling it back … But he was all fingers and thumbs. The rope seemed to squirm with a life of its own, and when he attempted to pull the tide-ring into place, the whole lot slipped out of his grasp.

‘Sky curse it!’ he shouted, his cheeks burning red with embarrassment and frustration.

‘Easy lad. Easy’ said Steg Jambles, patting his young protégé on the shoulder. ‘Let’s try that again …’

He paused. Tem Barkwater was staring down at the coil of rope at his feet, its threads now fanned out in eight unknotted strands like a …

‘Whip,’ breathed Tem, his face ashen-white.

Steg Jambles bent down and carefully picked the rope up and threw it into the shadows beneath the fore-deck gunwales.

‘Perhaps that’s enough for one day’ he said, and looked at Tem with concern. The lad was trembling, his bony knees knocking against each other.

Quint had first encountered him in the Timber Glades, pale and gaunt, and tethered to a whipping-post, being flogged. Having repaid the cruel wood merchant with a good hiding of his own, Quint had untied the youth and brought him on board. That was three months ago. Since then, the lad had never spoken of his past, nor of how he’d come to be punished so cruelly. Now, it seemed, he was about to speak. Steg sat down on the empty woodgrog barrel and waited.

‘My brother Cal and I were tricked by the wood merchant,’ Tem said in a quiet, hoarse voice.

Overhead, a flock of snowbirds let out their mournful cry. Tem didn’t seem to notice them. His eyes were still fixed on the spot on the deck where the frayed rope had been.

‘Go on,’ said Steg.

‘He said he’d teach us woodcraft and timbering, but that’s not what he wanted us for …’

‘No?’ said Steg, willing Tem to continue.

‘No,’ said Tem, his quavering voice barely audible. ‘We were to be bait.’

‘Bait?’ said Steg, puzzled.

For a while Tem didn’t say anything. Then he looked up and stared into his friend’s face. His eyes had a haunted look. He cleared his throat.

‘Of all the trees in the Deepwoods - lufwood, lul-labee, scentwood, stinkwood, sallowdrop - it is the bloodoak that the merchants prize most highly’ Tem began at last. ‘That was the one the wood merchant wanted to cut down for its timber.’ He snorted. ‘The most dangerous task in all the Deepwoods. To chop down the mighty bloodoak you must distract the terrible tarry vine that feeds it, distract it with …’ Tears sprang to Tem’s eyes.

‘Bait!’ said Steg again, appalled.

Tem nodded. ‘The wood merchant and his gang … They would tie us up at the end of long pieces of rope,’ Tem told him, the words faltering and faint. ‘Drive us into the forest, in those dark, fetid places where they suspected they might find bloodoaks - keeping at a safe distance themselves of course …

‘Then -

whoosh! -

suddenly out of nowhere, the vines would appear, wrapping themselves around an arm or a leg, or worst of all, our necks, and yank us forwards …’ He swallowed hard. ‘When they felt the

tugging on the rope, the loggers were supposed to run to us at once, cut the vines and cauterize them with blazing torches before they had a chance to sprout three vines where one had been before.

‘But … but…’ he stammered, close to tears. ‘They didn’t care about us, Cal and me … We … we didn’t matter. We were expendable. Sometimes the vine would drag us all the way to the tree … over the bleached bones of the bloodoak’s victims … Sometimes we were lifted up and dangled over the stinking maw of the tree, before they … they …’ He had clamped his hands over his ears. ‘Oh, I can still hear those mandibles slavering and slurping and clacking - and the awful

stench …’

Steg Jambles laid a comforting arm round the lad. ‘There, there, Tem, lad,’ he said. ‘Better to speak of such things than brood over them …’

‘Then one day, I was sick. The merchant left me behind in the Timber Glades. Just took Cal. When he got back, he was furious. Accused me of slipping my brother a knife, to help him escape. He dragged me over to the whipping-post and began to flog me with his whip - eight knotted lengths of copperwood twine …’ Tem shuddered, then turned to Steg. ‘But I didn’t care!’ He was smiling now, although tears coursed down his face.

‘You didn’t?’ said Steg.

‘No,’ said Tem, his eyes sparkling. ‘Because Cal, my brother, had escaped!’

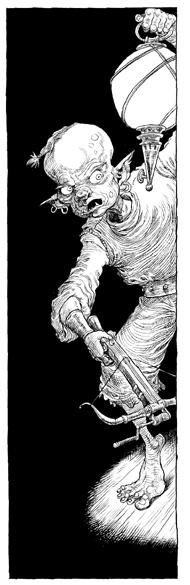

Below the fore-deck, in the gloom of the cargo-hold, Ratbit the mobgnome perched at the top of a tall stool. The simple oil lantern he was holding was set so low, it cast no light but a dull orange glow which illuminated the sour expression on his face.

‘Galerider

just repaired and fresh out of the sky-shipyard,’ he complained, ‘and still the little sky pests find their way in …’

Just then, the ship lurched to starboard, and from somewhere in the storeroom, Ratbit was sure he heard the sound of scratching. He fell still, cocked his head to one side. But there was nothing - nothing, that is, but the low buzz of the ratbirds chattering and the ship’s timbers creaking …

‘One little chink and Sky knows what slips through,’ he complained. ‘And before you know it, the cargo is blighted, and the profit’s gone …’

Critch! Critch!

There it was again. The mobgnome turned the lantern’s adjustable lighting-pin. It raised the wick and the cargo-hold was filled with light. There was a sound of scampering - and then silence. Lantern in his left hand, trigger-crossbow in his right, Ratbit slipped down off the stool and crept through the great storeroom, flashing the light up each of the narrow aisles between the stacks of crates.

‘Come out, come out, wherever you are,’ he whispered, his voice low and sing-song.

The ship gave another lurch and Ratbit leaned forward to steady himself. Beneath the floorboards, in the dark bowels

of the ship, the ratbirds twittered and squeaked.

‘Getting turbulent,’ said Ratbit. ‘Come in to shelter, have we?’