Clash of Kings (2 page)

Authors: M. K. Hume

‘My lady.’ A deep rumbling voice disturbed the girl’s moody thoughts. She turned too swiftly and, for a moment, the sky wheeled around her in a dizzying parabola. As her startled eyes rose to meet a pair of warm black irises in a broad, sunburned face, she felt a sudden chill of premonition that froze her tongue.

‘Are you well, child? Perhaps you’ve been too long in the sun?’

The girl’s vision narrowed until all she could see was the greatly magnified face of the warrior who stood over her. A dull roaring sound filled her ears as she watched the smiling mouth, so close to her own, open slowly to release a viscous flow of dark blood. The sun had dazzled her frightened eyes, but she was sure she could see a terrible, sucking wound that opened across the warrior’s strong, thick neck.

‘You are unwell, Lady Ygerne. Please allow me to help you back to your maid.’

Her legs folded, and as she slid into a dead faint Gorlois swept up the frail body of his betrothed who had been so newly delivered to Tintagel by her father. Concerned, the tribal king assessed the violet shadows below her eyes and the childish shape of her long lashes as they rested upon her pale cheeks.

‘She’s so small – and so young,’ he whispered to himself as he hefted her slight form in his arms, taking care not to drop the reins of his horse in the process. I hope she’s not sickly, he thought guiltily, even as he ordered his servants to ride ahead and prepare a hot, sweetened drink for her. He’d already lost one young wife to childbirth and, although his heart had not been given to the delicate little princess who had carried his stillborn son, he remembered the shrill desperation of her childbed cries with a sick dread. But his position demanded a wife and, more urgently, an heir, so he longed for a woman who could survive in his harsh and wildly beautiful domain.

‘She’s but ten years old, you fool!’ Gorlois told the wind as he climbed back onto his horse, still pressing her insubstantial length against his barrel chest. ‘She’s frightened, she’s lost and she’s far from her home.’ He was still searching her face with an expression of kind concern when her eyelids fluttered open.

‘There you are, my lady. I’ll soon have you back in a cosy room with a warm rug to cover your knees. You’ll feel better for a cup of hot milk from my kitchens. Tintagel is a wild place, and very isolated, but I have fairer houses in Isca Dumnoniorum that you will find comfortable and beautiful. The winds are warm and mild there. Tintagel is my country’s heart, so my wife must understand what makes it beat, but she need not love it, as I do.’ He smiled in a fatherly fashion as he observed her obvious confusion. ‘Never mind, pretty sweetling! When you have rested, perhaps my home will not seem so grim.’

Above his head, the birds continued to wheel as they squabbled in the wind-torn sky. Ygerne’s pale lips smiled tremulously, and she watched another falcon as it rode the thermals in the bright sky. She could imagine its golden eyes, seeking and seeking, and wondered if the bird could see her or would acknowledge her presence.

Without understanding her vision, the threat of the bird or the childish invitation in her actions, Ygerne turned her face and snuggled into the broad chest of Gorlois. She felt safe and loved for the first time in that long, strange and painful day. And as Gorlois felt her hair and her warm flesh pressed against his body, the fragility of her lovely face wound itself around his heart.

CHAPTER I

FROM MONA

Why should the worm intrude the maiden bud?

Or hateful cuckoos hatch in sparrows’ nests?

Or toads infect fair founts with venom mud?

Or tyrant folly lurk in gentle breasts?

Or kings be breakers of their own behests?

But no perfection is so absolute

That some impurity doth not pollute.

Shakespeare, ‘The Rape of Lucrece’

‘Daughter?’ An angry, masculine voice bellowed from the forecourt of the old villa at Segontium. Disturbed farm birds squawked and squabbled as they scrambled away from the huge horses. ‘Olwyn! Come out at once! Explain yourself!’

The sounds of nervous horses and a series of shouted orders, all delivered in a stentorian, impatient voice, forced Olwyn to put down her spindle, smooth her hair and woollen robe, and hurry out of the women’s quarters towards the atrium of the ancient house, where a tall, grizzled man was stripping off his fine leather gloves and woollen cloak, dropping them negligently over the nearest oaken bench.

His garb was careless, but his leathers, the well-tended furs and the embossed designs of hawks on his fine hide tunic indicated wealth and power. The heavy golden torc that proclaimed his status and a collection of brass, gold and silver arm rings, wrist bands and cloak pins were worn with such negligent grace that Melvig radiated the authority of a king. Even more telling were the disdainful eyebrows, the heavy lines of self-indulgence that drew down his narrow lips and a certain blunt directness in his stare that spoke of a nature accustomed to giving orders. On this particular afternoon, above a greying beard, his eyes were stormy and promised that squalls would soon come to her door.

‘Father! How nice to see you. Please, sit and be welcome. May I order the wine you like so much?’

Melvig ap Melwy made a grumpy gesture of assent and threw himself into a casual slouch, his long, still-muscular legs outstretched and his fingers tapping the armrest of his chair with ill-concealed irritation. Olwyn turned to her steward, who was hovering nervously behind his mistress. ‘Fetch the last of the Falernian wine that came from Rome. And some sweetmeats. I believe my father’s hungry.’

‘Hungry be damned, woman! I’m cross. And it’s your infernal brat who’s the cause of my upset. A man ought to be able to ride with his guard to see his daughter without risking assassination.’

Olwyn’s brow furrowed. Her father had always been a tyrant and a blusterer, but she loved him despite his faults. As the king of the Deceangli tribe, he often risked death from impatient claimants to his throne and ambitious invaders. But, so far, he had proved to be an elusive target and a vengeful survivor.

‘Idiot woman! It’s that daughter of yours. More hair than brain, I say, and thoughtless to a fault. She ran across the path right under the hooves of my horse. Only good luck prevented me from being thrown . . . and I’m too old to risk my bones.’

Olwyn smiled with relief, noting that her father showed no concern for the health of his granddaughter. Melvig was utterly egocentric.

‘You’re not very old, Father. You’re only fifty-two years by my reckoning, and you’re far too vigorous to be harmed by a twelve-year-old girl.’

‘Humpf!’ Melvig snorted. But he was pleased, none the less, and accepted the fine goblet of wine and ate every sweetmeat on the plate that was offered to him by Olwyn’s fumbling, nervous steward. When he had licked the last drops of honey from his huge moustache and drained the last of the wine in his cup, he fixed his daughter with his protuberant green eyes.

‘Olwyn, my granddaughter is near as tall as your steward, but she still runs wild through the dunes with her legs bare where she can be seen by any peasant who cares to look. When did she last have her hair brushed? And when did she last bathe? She’s little more than a savage!’

‘You exaggerate, Father. She’s high-spirited, and too young to be cooped up indoors. Would you take her from me? She’s all I have.’

‘And whose fault is that?’

But Melvig’s eyes softened a trifle, as much as that dour man was able to express feelings of sympathy. He remembered that Olwyn had lost her husband to a roving band of outlanders in her second year of marriage. Since Godric’s death, she had steadfastly refused to remarry, and preferred to live with her servants and her daughter on the wild stretch of coast below Segontium. In Melvig’s opinion, his daughter was too young at twenty-five summers to have turned her face away from life. She still had all her teeth, her skin was unlined and she had proved that she was fertile. If she had any loyalty to her clan, he thought with another spurt of temper, she would have given him another grandson years ago.

But Olwyn’s hazel eyes were slick with unshed tears, so Melvig was moved to pat her arm awkwardly to show his understanding of her fears. Although he was an impatient father, this particular daughter had always been a favoured child, for in all the details that mattered Olwyn had been obedient and circumspect.

‘I’ll not take her from you, daughter, so have done with all this fussing. But you must be aware that she’s as wild as a young filly and as heedless as a foolish coney that dares the hawks to strike. Would you have her stolen and raped? No? Then you must see to her education, Olwyn, because I’ll be searching for a husband for her at the end of winter.’

Olwyn’s heart sank and a single tear spilled from her thick, overlong lashes to roll down her pale cheek. Melvig used his large, calloused thumb to wipe away the salty trail with affectionate impatience.

‘May the gods take thee, woman,’ he whispered softly. ‘Don’t look at me as if I steal your last crust of bread. I’ll not take her yet, but the day will come soon, Olwyn, so you’d best be considering how you are to spend the rest of your days. Now, where are my travelling bags?’

Too wise to waste time in fruitless argument, Olwyn saw to the comfort of her father first, and then sent her maid to find her moon-mad daughter.

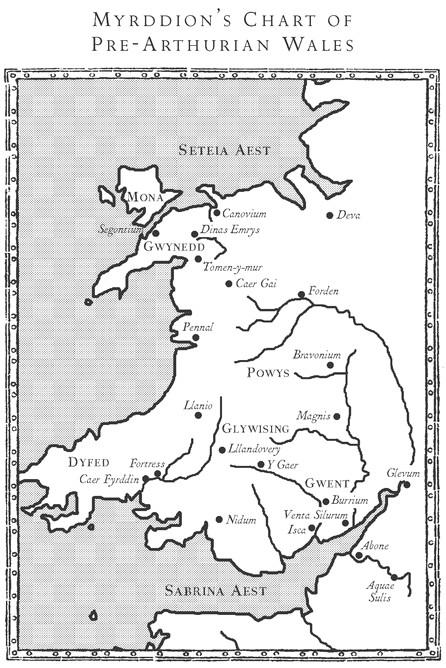

Segontium wasn’t a large town, but it bore the stamp of the Roman occupation in its small forum, brick and stone buildings and sturdy wall. Once, over a thousand Roman troops had been quartered in the surrounding fields, allowing Paulinus, and Agricola after him, to smash all resistance by the Ordovice tribes. Above a pebble-strewn shoreline, Segontium looked towards the island of Mona where, for ever after, all good Celts would remember the shameful slaughter of the druids, young and old, male and female, as they faced their implacable enemy on the ancient isle of sacred memory. Rome’s predatory legions had known that the druids held sway over the tribal kings. During the rebellion, leaving Boudicca to rage around Londinium, Paulinus had hastened north to rip the living, beating heart out of the Celts on Mona rather than bring the Iceni queen to heel. His desperate plan had succeeded, for few druids had escaped the bloody massacres, and Paulinus had crushed the superstitious, suddenly rootless Celts. In one final insult, the Christian priests had decided to take root on Ynys Gybi, a tiny isle huddled against Mona’s flanks.

Segontium bore its taint of blood, while something heavy remained in the Latin name to cause the least superstitious man to furrow his brow and make the sign to ward off evil. The dark shores in winter, the screams of gulls and the sea-tainted air that was softened by the earth and trees of Mona warned its neighbours to beware.

Olwyn had come to Godric’s house with joy, in full knowledge that her man had no Roman blood in him. Their ancient home was cobbled together from a ruin, using stones taken from Roman villas and the conical houses of the Celts, but Olwyn felt no taint in the clean winds that scoured the corridors of fallen leaves and the sand whipped into corners by storms. Situated a little to the south of the shadow of Mona, their snug house suffered the vicious blows of the Hibernian winds, but Olwyn was content. Even the worn floor tiles, with their alien designs of sun, stars, moons and constellations held no fears for her. Wind, clean sunshine, driving rain and freezing snow combined to drive any sour humours from the house and purge it of the Roman poison.

But Godric had ridden away to protect his uncle’s fields from tribal incursions, and when he returned he was tied over his horse’s flanks, wrapped in greasy hides and pallid in death. Olwyn had been too numb to weep, even when she had unbound her husband’s corpse and exposed the many wounds made by arrows in his cold, marbled flesh. A stump of shaft protruded from the killing injury over his heart, and Olwyn had been so lost to propriety that she had struggled to tug it free.

Eventually, after she had used a sharp knife to slice the flesh that held the cruel barbs of the arrowhead in place, the small length of shaft had seemed to leap out of Godric’s breast with an ugly, sucking noise. In a daze, she had washed her husband’s flesh, oiled his hair and plaited it neatly before dressing him in his finest furs and a woollen tunic. Finally, she bent to kiss his mouth, although the faint, sickly odour of death almost made her vomit. Blessedly, her tears began to fall.

All the comforting obsequies of death were observed but only one duty consumed Olwyn’s waking moments. The arrowhead was separated from the remnants of its shaft and Olwyn laboured for many hours to drive a narrow hole through the wicked iron barb. Then, after months of toil, she hung the arrowhead round her daughter’s neck by a soft plait of leather.

Melvig, her father, had been repulsed by the gesture, but Olwyn was a strange, obsessive creature who lacked his sturdy practicality, so he said nothing. If he had been honest, Melvig would have confessed that his stubborn, self-contained daughter frightened him a little with her intensity. Like all her kin, Olwyn was wild and strange. Melvig often wondered why he had taken a black-haired hill woman as his second wife, although her blatant sexuality had certainly stirred his loins. The gods were aware of his frustration when she produced no sons, only daughters, and all of them peculiar!