Civilization: The West and the Rest (24 page)

Although that nation was cradled in liberty, raised on freedom, and maintained by liberty alone … it is a marvel … that so weak and complicated a government as the federal system has managed to govern them in the difficult and trying circumstances of their past …

In his view, the United States constitution would require ‘a republic of saints’ to work.

64

Such a system could not possibly work in South America:

Regardless of the effectiveness of this form of government with respect to North America, I must say that it has never for a moment entered my

mind to compare the position and character of two states as dissimilar as the English American and the Spanish American.

So Bolívar’s dream turned out to be not democracy but dictatorship, not federalism but the centralization of authority, ‘because’, as he had put it in the Cartagena Manifesto, ‘our fellow-citizens are not yet able to exercise their rights themselves in the fullest measure, because they lack the political virtues that characterize true republicans’.

65

Under the constitution he devised – which, among other peculiarities, featured a tricameral legislature – Bolívar was to be dictator for life, with the right to nominate his successor. ‘I am convinced to the very marrow of my bones’, he declared, ‘that America can only be ruled by an able despotism … [We cannot] afford to place laws above leaders and principles above men.’

66

His Organic Decree of Dictatorship of 1828 made clear that there would be no property-owning democracy in a Bolivarian South America, and no rule of law.

The second problem had to do with the unequal distribution of property itself. After all, Bolívar’s own family had five large estates, covering more than 120,000 acres. In post-independence Venezuela, nearly all the land was owned by a creole elite of just 10,000 people – 1.1 per cent of the population. The contrast with the United States is especially striking in this regard. After the North American Revolution, it became even easier for new settlers to acquire land, whether as a result of government credits (under various acts from 1787 to 1804) or of laws like the General Pre-emption Act of 1841, which granted legal title to squatters, and the Homestead Act of 1861, which essentially made smallholder-sized plots of land free in frontier areas. Nothing of this sort was done in Latin America because of the opposition of groups with an interest in preserving large estates in the countryside and cheap labour in crowded coastal cities. In Mexico between 1878 and 1908, for example, more than a tenth of the entire national territory was transferred in large plots to land-development companies. In 1910 – on the eve of the Mexican Revolution – only 2.4 per cent of household heads in rural areas owned any land at all. Ownership rates in Argentina were higher – ranging from 10 per cent in the province of La Pampa to 35 per cent in Chubut – but nowhere close to those in North America. The rural property-ownership rate in the United States in 1900 was just under 75 per cent.

67

It should be emphasized that this was not an exclusively US phenomenon. The rate of rural property-ownership was even higher for Canada – 87 per cent – and similar results were achieved in Australia, New Zealand and even parts of British Africa, confirming that the idea of widely dispersed (white) landownership was specifically British rather than American in character. To this day, this remains one of the biggest differences between North and South America. In Peru as recently as 1958, 2 per cent of landowners controlled 69 per cent of all arable land; 83 per cent held just 6 per cent, consisting of plots of 12 acres or less. So the British volunteers who came to fight for Bolívar in the hope of a share in the

haberes militares

ended up being disappointed. Of the 7,000 who set off for Venezuela, only 500 ended up staying. Three thousand died in battle or from disease, and the rest went home to Britain.

68

The third – and closely related – difficulty was that the degree of racial heterogeneity and division was much higher in South America. Creoles like Bolívar hated

peninsulares

with extraordinary bitterness, far worse than the enmity between ‘patriots’ and ‘redcoats’ even in Massachusetts. But the feelings of the

pardos

and slaves towards the creoles were not much more friendly. Bolívar’s bid for black support was not based on heartfelt belief in racial equality; it was a matter of political expediency. When he suspected Piar of planning to rally his fellow castas against the whites, he had him arrested and tried for desertion, insubordination and conspiring against the government. On 15 October 1817 Piar was executed by a firing squad against the wall of the cathedral at Angostura, the shots audible in Bolívar’s nearby office.

69

Nor was Bolívar remotely interested in extending political rights to the indigenous population. The constitutional requirement that all voters be literate effectively excluded them from the political nation.

To understand why racial divisions were more complex in South America than in North America, it is vital to appreciate the profound differences that had emerged by the time of Bolívar. In 1650 the American Indians had accounted for around 80 per cent of the population in both North America and South America, including also Brazil. By 1825, however, the proportions were radically different. In Spanish America indigenous peoples still accounted for 59 per cent of the population. In Brazil, however, the figure was down to 21 per cent, while in North America it was below 4 per cent. In the United States and Canada massive migration from Europe was already under way, while the expropriation of the Indian peoples and their displacement to ‘reservations’ of marginal land was relatively easily achieved by military force. In Spanish America the Indians were not only more numerous but were also, in the absence of comparably large immigration, the indispensable labour force for the

encomienda

system. Moreover, as we shall see, the institution of African slavery had quite different demographic impacts in the different regions of European settlement.

70

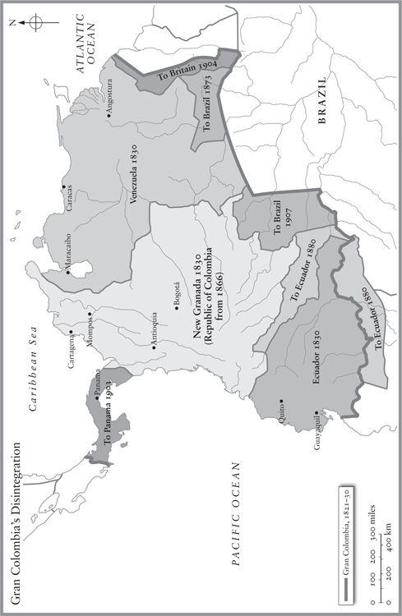

In the end, then, Bolívar’s vision of South American unity proved impossible to realize. After revolts in New Granada, Venezuela and Ecuador, the proposed Andean Confederation was rejected and Gran Colombia itself disintegrated when Venezuela and Quito seceded. The victor was Bolívar’s former confederate, the caudillo José Antonio Páez, who had thrust himself forward as the proponent of a narrow Venezuelan nation-state.

71

A month before his death from tuberculosis in December 1830, having resigned his posts of president and captain-general, Bolívar wrote a last despairing letter:

… I have ruled for twenty years, and from these I have derived only a few certainties: (1) [South] America is ungovernable, for us; (2) Those who serve a revolution plough the sea; (3) The only thing one can do in America is to emigrate; (4) This country will fall inevitably into the hands of the unbridled masses and then pass almost imperceptibly into the hands of petty tyrants, of all colours and races; (5) Once we have been devoured by every crime and extinguished by utter ferocity, the Europeans will not even regard us as worth conquering; (6) If it were possible for any part of the world to revert to primitive chaos, it would be America in her final hour.

72

It was a painfully accurate forecast of the next century and a half of Latin American history. The newly independent states began their lives without a tradition of representative government, with a profoundly unequal distribution of land and with racial cleavages that closely approximated to that economic inequality. The result was a cycle of revolution and counter-revolution, coup and counter-coup, as

the propertyless struggled for just a few acres more, while the creole elites clung to their haciendas. Time and again, democratic experiments failed because, at the first sign that they might be expropriated, the wealthy elites turned to a uniformed

caudillo

to restore the status quo by violence. This was not a recipe for rapid economic growth.

It is not by chance that today’s President of Venezuela, ‘El Comandante’ Hugo Chávez, styles himself the modern Bolívar – and indeed so venerates the Liberator that in 2010 he opened Bolívar’s tomb to commune with his spirit (under the television arc lights). An ex-soldier with a fondness for political theatre, Chávez loves to hold forth about his ‘Bolívarian revolution’. All over Caracas today you can see Bolívar’s elongated, elegantly whiskered face on posters and murals, often side by side with Chávez’s coarser, chubbier features. The reality of Chávez’s regime, however, is that it is a sham democracy, in which the police and media are used as weapons against political opponents and the revenues from the country’s plentiful oil fields are used to buy support from the populace in the form of subsidized import prices, handouts and bribes. Private property rights, so central to the legal and political order of the United States, are routinely violated. Chávez nationalizes businesses more or less at will, from cement manufacturers to television stations to banks. And, like so many tinpot dictators in Latin American history, he makes a mockery of the rule of law by changing the constitution to suit himself – first in 1999, shortly after his first election victory; most recently in 2009, when he abolished term-limits to ensure his own indefinite re-election.

Nothing better exemplifies the contrast between the two American revolutions than this: the one constitution of the United States, amendable but inviolable, and the twenty-six constitutions of Venezuela, all more or less disposable. Only the Dominican Republic has had more constitutions since independence (thirty-two); Haiti and Ecuador are in third and fourth positions with, respectively, twenty-four and twenty.

73

Unlike in the United States, where the constitution was designed to underpin ‘a government of laws not of men’, in Latin America constitutions are used as instruments to subvert the rule of law itself.

Yet before we celebrate the long-run success of the British model of colonization in North America, we need to acknowledge that in one

peculiar respect it was in no way superior to Latin America. Especially after the American Revolution, the racial division between white and black hardened. The US constitution, for all its many virtues, institutionalized that division by accepting the legitimacy of slavery – the original sin of the new republic. On the steps of the Old Exchange in Charleston, where the Declaration of Independence was read, they continued to sell slaves until 1808, thanks to article 1, section 9, of the constitution, which permitted the slave trade to continue for another twenty years. And South Carolina’s representation in Congress was determined according to the rule that a slave – ‘other persons’ in the language of the constitution – should be counted as three-fifths of a free man.

How, then, are we to resolve this paradox at the heart of Western civilization – that the most successful revolution ever made in the name of liberty was a revolution made in considerable measure by the owners of slaves, at a time when the movement for the abolition of slavery was already well under way on both sides of the Atlantic?

Here is another story, about two ships bringing a very different kind of immigrant to the Americas. Both left from the little island of Gorée, off the coast of Senegal. One was bound for Bahia in northern Brazil, the other for Charleston, South Carolina. Both carried African slaves – just a tiny fraction of the 8 million who crossed the Atlantic between 1450 and 1820. Nearly two-thirds of migrants to the Americas between 1500 and 1760 were slaves, increasing from a fifth prior to 1580 and peaking at just under three-quarters between 1700 and 1760.

74

At first sight, slavery was one of the few institutions that North and South America had in common. The Southern tobacco farm and the Brazilian

engenho

alike came to rely on imported African slaves, once it became clear that they were cheaper and could be worked harder than indentured Europeans in the North and native Americans in the South. From the King of Dahomey down, the African sellers of slaves made no distinction; they were as happy to serve British slave-buyers

as Portuguese, or for that matter their traditional Arab clients. A trans-Saharan slave trade dated back to the second century

AD

, after all. The Portuguese found fully functional slave markets when they arrived in Benin in 1500.

75

From the vantage point of a captive African held in the slave house at Gorée, it seemed to make little difference whether he was loaded on to the ship bound for North or South America. The probability of his dying in transit (roughly one in six, since we know that 16 per cent did not survive the ordeal) was about the same.