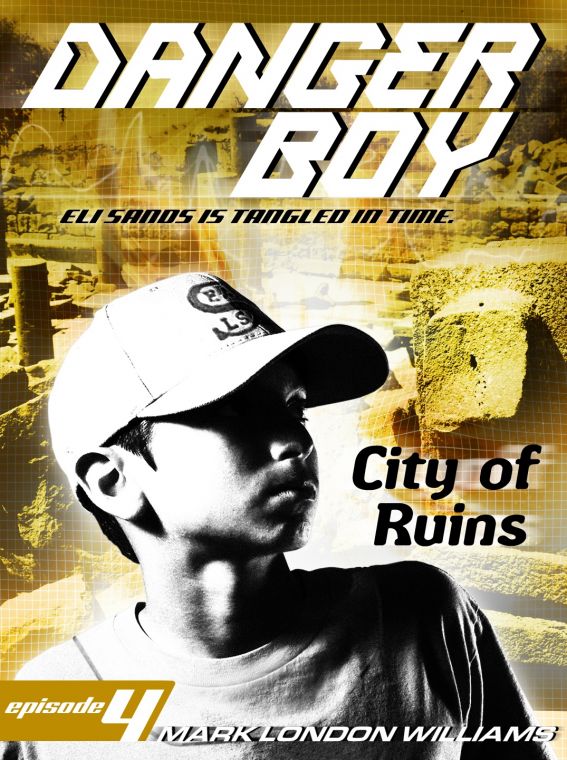

City of Ruins

Authors: Mark London Williams

Tags: #adventure, #science, #baseball, #dinosaurs, #jerusalem, #timetravel, #middle grade, #father and son, #ages 9 to 13, #biblical characters, #future adventure

DANGER BOY

City of Ruins

Mark London Williams

Danger Boy: City of Ruins

By Mark London Williams

Copyright 2007 Mark London Williams

All Rights Reserved

Smashwords Edition

Candlewick Press Edition 2007

This one’s for those who came before,

Especially the grandfolks:

Don and Cathryn; Lil and Lionel

Prologue

Jerusalem 583 B.C.E

“

I wish I could be eight forever…”

The boy keeps throwing rocks against the ruins of

the palace wall, trying to hit the outline of a man he’s drawn

there. The sketch looks like it was done with ash, with charcoal.

“If I could stay eight, then maybe no more bad things could happen

ever again. Or if I could go back to being seven, that would be

better — that was before all the bad things happened. But no one

can go backwards in time.”

The rock hits the charcoal man in the head. “There.

That’s for the soldier who took my parents.”

Another rock hits the chalk soldier in the face.

The boy remembers all the screams — remembers the

men with their spears and swords and metal helmets, coming and

slashing their way through his city, Jerusalem. Killing the people,

and the animals, and setting fire to everything that was left.

The idea wasn’t to “capture” the city, but to

destroy it.

The boy was small enough to hide in an empty clay

jug that stood on the floor of his house. A jug used for storing

olive oil.

His bigger sister wasn’t so lucky. She didn’t find a

hiding place in time.

When one of the soldiers kicked the jug over and

watched it roll away, before setting fire to his family’s house,

the boy was careful not to scream, the way his parents had warned

him not to.

But he couldn’t help hearing their screams — and his

sister’s — as they were taken away.

Not everyone was killed — many were taken away to be

slaves, slaves for the conquering king, who, like all kings, was

looking for ways to make his empire grow larger.

And those not killed or taken were simply left

behind. The old and broken, or, like the boy, the very young. Left

behind to fend for themselves in a ruined city, with no food, no

markets, and no buildings, as each day grew colder, and fall turned

into winter.

There weren’t even any walls left, to clearly define

where the city had been.

But the walls were for keeping invaders out. Since

they failed, what was their point?

Who would want to invade a City of Ruins?

Who would even want to visit it?

That’s why this new visitor, this older boy, this

young man, is so strange to the first boy, throwing his rocks.

He would seem stranger still, if the first boy knew

he was a Time Traveler.

The Time Traveler stands, watching the boy, his

lingo-spot tingling, letting him understand all the words in his

own tongue.

And with understanding comes a soft, sad, smile. He

doesn’t tell the boy that as it turns out, you can go backwards in

time. The thing you can’t do is stay eight forever.

The Time Traveler remembers a time when he was

younger, when he threw rocks, when maybe he wished he could be

eight, or nine, or ten forever. There were no ruined cities around

him then, back in New Jersey. Back in Herronton Woods, running home

to a house he thought he might live in forever, with a family he

didn’t think could ever come apart. He’d run, pretending to be a

Barnstormer character — a monster from his favorite Comnet game —

playing with his friend Andy. Andy.

Anderson Walls.

He hasn’t seen Andy, or heard from him in — months?

Years? Or really, now that he’s become unstuck in time, become

“Danger Boy,” maybe centuries. It certainly feels like

centuries.

“

What’s your name?” the first boy asks. He keeps

throwing rocks at the soldier on the wall. And though the burnt

orange rays from the setting sun make the boy squint, his aim is

steady.

“

Eli.”

“

Isn’t that the name of a priest? Were you a

priest at the temple?”

Eli shakes his head. He can understand the boy, but

knows the boy won’t be able to understand his English. “No.”

“

Are you one of those prophets?”

“

No.” Another shake.

“

Then why would you come here? Did they leave you

behind, too? Did you hide? Did you escape?”

Eli just shrugs, and works on making his smile as

sympathetic as possible. The boy keeps talking.

“

I mean from the soldiers. The Babylonians. They

took everyone they wanted, to make them slaves. Like my mother, and

father. My sister, too. There must be some reason they left

you.”

Thunk.

Another rock grazes the soldier’s

arm.

Eli shrugs again — he wishes he could talk to the

boy, but can’t risk sharing any of the lingo-spot, since the side

effects of the substance are becoming increasingly unpredictable.

Instead, he looks around for a stone.

Thunk.

This time the boy hits the soldier

right in the head. The sun has shifted lower and the light becomes

redder, so that the ruined wall, and the charcoal invader, look

like they’re covered in blood.

Eli holds up his own stone, letting the boy know

he’d like a turn.

Now it’s the boy’s turn to shrug, trying too hard to

show he’s beyond caring about anything now.

Eli looks at the boy, then stares hard at the wall,

telling himself that the charcoal man isn’t a soldier, but a

catcher, waiting for a pitch. He winds up, shakes off a signal,

shakes off another one, then nods — and throws.

“

Strike!”

A swamp zombie just swung at a third strike, for the

final out of the inning.

“

You’re outta there!” Eli jerks his thumb,

remembering how much fun it was when the monsters were easy to

beat, but he doesn’t realize how loud he’s yelling and the boy

jumps back.

“

Hey!” The boy clutches another rock in his hand,

and it looks like he might throw this one at Eli.

Eli holds out his hands and tries to explain. “I’m

playing Barnstormers.”

“

I still don’t understand you…” the boy says.

“Where are you really from? Why did you come here?” and Eli can see

he’s shaking now, trembling all over, trying to be brave, but on

the verge of tears.

Eli steps closer. “It’s all right.”

“

I can’t understand you!”

“

I’m not here to hurt you.”

“

Just stay away.”

“

I know what you’re feeling. I do.” Another

step.

“

I mean it.”

And closer still, as the red sun falls farther below

the horizon, and the bloody light turns to shadow, and Eli is next

to the boy, who looks up at him and says “don’t hurt me.”

Eli takes the boy in his arms, this skinny dirty boy

covered with rags, who has no food, no house, no family, and lets

him cry.

The boy’s arms go around Eli, and he starts

sobbing.

“

The soldiers came,” he says.

Eli nods. He thinks of the mobs in Alexandria. The

picture of the mother and her son in Nazi Germany.

Even the guards in the tunnels below San Francisco,

and around his father’s lab, in the Valley of the Moon.

The soldiers always come.

And he wonders, now that he’s turned thirteen, if

this is what it means to grow up. That you have to help soak up the

tears for all the kids younger than you, and tell them everything

will be okay.

The boy keeps crying and Eli suddenly realizes he

feels responsible for him. But what can he do?

He doesn’t know anything about ancient Jerusalem,

about where to go, especially where to go after the city’s been

destroyed in a war.

He’ll just have to take the boy back to see the

healer woman, Huldah. Even though she told him he’d have to leave

for a while, while she found out if there was still a chance to

save his friend Thea.

Or whether her slow pox was getting worse.

Chapter One

Eli: House of David

February 2020 C.E.

Ow! Even moving my eyes hurts.

I’m trying to follow the Comnet image as it

goes across the room, of a guy in a baggy baseball uniform and long

hair and beard running around the bases after hitting a home run,

but even the slight turn of my eye muscles moves my head a little,

which pulls against all the restraints and straps and rods holding

me in. Holding me still.

When they told me “not to move a muscle,” I

guess they meant it.

The DARPA people — the Defense Advanced

Research Projects Agency — are trying to get another “particle

scan” of my body, a kind of roadmap of all my atoms. They say the

scan will be like a “circuit board” showing the microscopic

currents flowing through me, from atom to atom. Maybe even particle

to particle.

“It’s the best we can do, since we don’t

really want to break your body apart to look at your atoms. After

all, we don’t want to turn you into some kind of nuclear bomb!”

That’s what passes for a “joke” here at DARPA, and it was told to

me by a woman whose codename is “Thirty.”

It was the only name she’d give me, and she

took it from a baseball player’s uniform, from a picture on a ’gram

I was holding, back when I was a younger kid. Back when the whole

“Danger Boy” thing began. I don’t actually know her “real”

codename. Or her real

real

name.

She’s named after a number on a shirt.

Number 33, Green Bassett had a mysterious past that

made him one of the bearded squad’s early “stars.” He was rumored

to be a World War I deserter, but nobody was sure from which side.

For the 3.3 years he was touring with the team, he always hit 33

home runs per season, and batted .333. He said this was deliberate,

that he was trying to “use numbers to bring a message to the fans,

to let them know it’s later than they think.” Although he never

fully explained what he meant, he was undoubtedly referring to the

fact that the House of David squad, like the community they

represented, believed that the end times were near, that God would

come down to Earth, and life as it was presently known would have a

fiery end — and rebirth.

Bassett later disappeared from the squad as

mysteriously as he had arrived, during a trip to Oklahoma.

So to pass the time I’m watching a Comnet

documentary on the old “House of David” barnstorming baseball

team.

I found out about them when I was trying to

find a “Barnstormers” game on the Comnet screen in my room, here in

the old BART tunnels under San Francisco, where DARPA still keeps a

secret compound. When I used the Comnet, I mostly got

ACCESS DENIED

messages when I tried to read the news,

or see if there was any mail for me.

But there were a few Comsites I was allowed

to see. One search for

Barnstormers

brought me to this House

of David baseball team locus, with all the guys in their baggy

outfits, and all the hair and beards, because in their religion,

they didn’t believe in cutting them.

These House of David guys were playing

baseball, and at the same time, trying to end the world as they

knew it.

It was one of the only times — outside of being a

Yankee fan — when someone believed that the very act of playing

baseball could affect not only the future of the earth, but of the

very heavens themselves.

The House of David traveling squad considered

putting on baseball games for Americans who were interested in the

still-new sport part of doing “good works” — making things right in

the world they lived in now, and preparing the way for the world to

come.