City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (52 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

Bayezit had been thorough in the development of his navy: he had done more than just build the ships. Seeking expertise in naval matters, he had recruited Muslim corsairs from the Aegean to his naval command – privateers who plundered Christian vessels in the name of holy war and were skilled both in practical ship handling and open sea warfare. Two experienced corsair captains, Kemal Reis and Burak Reis, already well known to the Venetians for raids on their shipping, were in the fleet now making its

ponderous way round the coast of southern Greece. This injection of expertise gave the sultan the confidence to push his fleet west into the Ionian Sea, the threshold of Venice’s home waters.

The Ottoman fleet, though immense, was of variable quality. There were in all around 260 ships – including sixty light galleys, the two mammoth round ships, eighteen smaller round ships, three great galleys, thirty

fuste

(miniature galleys) and a swarm of smaller craft. As well as sailors and oarsmen, the great galleys and round ships carried a large number of janissaries, the sultan’s own crack troops. The giant round ships each held a thousand fighting men. This armada probably consisted of thirty-five thousand men in total.

Grimani’s fleet was smaller. It numbered ninety-five ships – a mixture of galleys and round ships, including two carracks of their own of more than a thousand tons, carrying both cannon and soldiers. The Venetians had recently employed squadrons of heavy carracks to hunt down pirates, but they had never before brought together such a large mixed fleet of oared and sailing ships. Grimani had about twenty-five thousand men. Despite the discrepancies in fleet size, he was supremely confident. He knew from the Greek sailors that he had more heavy ships, both carracks and great galleys, which could shatter his opponent’s line. He wrote to the senate accordingly: ‘Your excellencies will know that our fleet, by the Grace of God, will win a glorious victory.’

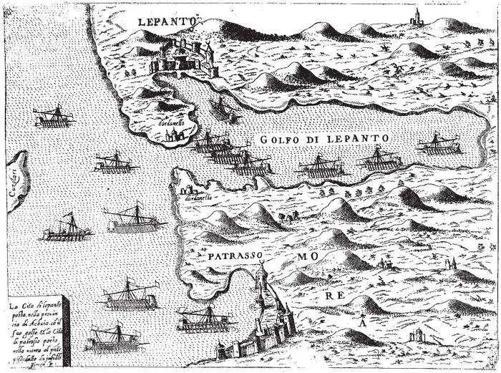

In late July, off the south-western tip of Greece, Grimani made contact with the Ottoman fleet between Coron and Modon and began tracking its progress, seeking the opportunity to attack. The world’s two largest navies – a total of 350 ships and sixty thousand men – moved in parallel up the coast. It quickly became apparent that the Turks had no interest in battle; their mission was to deliver cannon to Lepanto, and they acted accordingly, hugging the coastline so tightly that some of the vessels ran aground and the Greek crews deserted. On 24 July the Ottoman admiral took his fleet into the shelter of Porto Longo on the island of Sapienza. It was a place of misfortune in Venetian history. It was

here that Nicolo Pisani, Vettor’s father, had been routed by the Genoese 150 years earlier.

In Venice people waited anxiously. Priuli perceived a world in ominous turmoil: ‘In all parts of the world now there are upheavals and warlike disturbances and many powers are on the move: the Venetians against the Turks, the French king and Venice against Milan, the Holy Roman Emperor against the Swiss, in Rome the Orsini against the Colonesi, the [Mamluk] sultan against his own people.’ On 8 August he noted an unsettling rumour from quite another source, like the dull vibration of an earthquake on the far side of the world. Letters from Cairo, via Alexandria, ‘from people coming from India, assert that three caravels belonging to the king of Portugal have arrived at Aden and Calicut in India and that they have been sent to find out about the spice islands and that their captain is Columbus’. Two of these had been shipwrecked, while the third had been unable to return because of the counter-currents and the crew had been forced to journey overland via Cairo. ‘This news affects me greatly, if it’s true; however I don’t give credence to it.’

Grimani, meanwhile, had been waiting for the Turkish fleet to push on from Sapienza. When it did so he hung his ships out to sea and continued tracking it from headland to headland in a game of cat and mouse. In the hot summer days, the breeze dies in the middle of the day off the Greek coast; the captain-general was forced to await the advantage of a steady onshore wind to bear down on his prey. His moment seemed to have come on the morning of 12 August 1499 as the Ottomans pulled clear of the bay the Venetians called Zonchio into a stiff onshore breeze.

Grimani now had the target within his sights; the long line of enemy ships was strung out along miles of open water in front of him and to leeward. He was faced with some unique difficulties in ordering his ships – the combination of sail-powered carracks, heavy merchant galleys and light but faster war galleys was tricky – but he drew up his ships in line with established practice: the heavy vessels – the sailing ships and great galleys – in the vanguard

to shatter the enemy line, the lighter racing galleys behind, ready to dart out as their opponents scattered. He had given clear written instructions to the commanders to advance ‘at sufficient distance not to get entangled or break oars, but in as good order as possible’. He made it clear that men would be hanged for booty hunting during the battle; any captains who failed to engage the enemy would also be strung up. Such orders were standard before battle but perhaps Grimani had got wind of some dissent from the

patroni

of the requisitioned merchant galleys. The clarity of his orders would later be disputed. Domenico Malipiero considered them to be ‘riddled with flaws’; Alvise Marcello, commander of all the round ships and a man with something to hide, declared that the orders had been altered confusedly at the last minute. Whatever the truth, Grimani had just hoisted a crucifix and sounded the trumpets for the attack when his composure was ruffled by the unbidden arrival of an additional detachment of small ships under their commander, Andrea Loredan, an experienced hands-on seaman, popular with crews.

Loredan was in fact guilty of a breach of discipline. He had deserted his post at Corfu to share the glory of the hour. Grimani was irritated at having the attack disrupted; he was also put out at being upstaged. He reproved the newcomer for flouting orders but decided to let him lead the charge in the

Pandora

, one of the Venetian round ships, accompanied by Alban d’Armer in another. These were the largest ships in the fleet, each about 1,200 tons. Loredan had also come with scores to settle. He had spent considerable time hunting the corsair Kemal Reis; he now believed that he had his prey in sight, commanding the largest of the sailing ships built by Gianni; its captain was in fact the other corsair leader, Burak Reis. Excited cries of ‘Loredan! Loredan!’ rang across the fleet as the seamen watched their trophy ships closing on the invulnerable 1,800-ton floating fortress.

What ensued was a signal moment in the evolution of naval warfare, a foretaste of Trafalgar. As the three super-hulks closed, both sides opened up with broadsides from their heavy cannon in

a terrifying display of gunpowder weaponry: the roar of the guns at close range, the smoke and spitting flashes of fire astonished and unnerved those watching from the other ships. Hundreds of fighting troops, protected by shields, massed on the decks and fired a blizzard of bullets and arrows; forty feet higher in the crow’s nests, crested by the lion flag of St Mark or the Turkish moon, men fought an aerial battle from top to top, or hurled barrels, javelins and rocks onto the decks below; a swarm of light Turkish galleys worried the stout wooden hulls of the Christian round ships that reared above them. Men struggled to climb the sides and fell back in the sea. Despairing heads bobbed among the wreckage.

In contrast the other Venetian front-line commanders hardly moved. The vanguard of the Christian fleet seems to have been gripped by a terrible indecision at the appalling spectacle before them. Alvise Marcello, the captain of the round ships, captured one light Turkish vessel and withdrew – though Marcello himself would give a much more dramatic account at the end of the day. Only one of the great galleys entered the fray under its heroic captain, Vicenzo Polani. It was set upon by a swarm of Turkish galleys in a battle that lasted two hours. In the smoke and confusion, ‘everyone thought it lost; a Turkish flag was hoisted on her, but she was stoutly defended and massacred a large number of Turks … and it pleased God to send a breath of wind; she hoisted her sails and escaped from the clutches of the Turkish fleet … maimed and burned; and if’, Malipiero went on, ‘the other great galleys and round ships had followed her in, we would have shattered the Turkish fleet’.

Almost none of the other great galleys and carracks did. There was no response to Grimani’s frantic trumpet calls. The command structure collapsed. Orders were given and disobeyed or countermanded, Grimani failed to lead by example, while many of the more experienced captains were locked in the rear. The oarsmen in these galleys behind urged the heavy ships forward with shouts of ‘Attack! Attack!’ When this failed to provoke a response, howls

of ‘Hang them!’ rang across the water. Only eight ships entered the fray. Most were the lighter vessels from Corfu, vulnerable to gunfire. One was quickly sunk, which further dampened enthusiasm for the fight. When Polani’s ship emerged, scorched, battered, but miraculously still afloat, the other great galleys followed her to windward.

Meanwhile the

Pandora

and Alban’s ship continued to grapple with the carrack of Burak Reis. The three ships crashed together so that the men were fighting hand to hand, ship to ship. The battle continued for four hours until the Venetians seemed to be gaining the advantage; they clasped their opponent with grappling chains and prepared to board. Exactly what happened next is unclear; the ships were locked together, unable to separate, when fire broke out on the Ottoman vessel. Either by chance or as an act of self-destruction – for Burak Reis was pressed hard and close to despair – the powder supply in the Turkish ship exploded. The flames ran up the rigging, seized the furled sails and roasted the men in the foretops alive. The blackened stumps of the masts crashed to the decks. Those below were either instantly engulfed in flames where they stood or hurled themselves over the side. The watching ships observed this living pyramid of fire in rigid horror. It was maritime catastrophe on a new scale.

But the Turks somehow held their nerve. While their indestructible battleship, carrying a thousand crack troops, ignited in front of them, the light galleys and frigates scuttled about rescuing their own men from the debris and executing their opponents in the water. On the Christian side they just watched, aghast. Loredan and Burak Reis disappeared in the inferno, Loredan, according to legend, still holding the flag of St Mark. More painfully, there was no effort to rescue the survivors. The captain of the other large carrack, d’Armer, escaped from his burning ship in a small boat but was captured and killed. ‘The Turks’, wrote Malipiero miserably, ‘picked up their own men in long boats and brigantines and killed ours, because we on our part showed no

such pity … and so was done great shame and damage against our Signoria, and against Christianity.’

And so it had been. The battle of Zonchio had not been lost. It had just not been won. Venice had flunked the chance to stem the Ottoman advance. In psychological terms 12 August was an utter catastrophe. Cowardice, indecision, confusion, reluctance to die for the flag of St Mark: the events at Zonchio inflicted deep and long-lasting scars on the maritime psyche. The disaster at Negroponte could be put down to a poor appointment or the inadequacy of a single commander; the debacle at Zonchio was systemic. It revealed fault lines in the whole structure. It is true that the senate had repeated its mistake and appointed an inexperienced man – largely for reasons of cash – but Grimani was not solely responsible. By the end of the day, with the cordite still on their hands and already perceiving hideous disgrace, the major participants were drafting reports.

They all contained conditionals to the effect of ‘if someone else had done (or not done) something we would have won a glorious victory’. Grimani’s came, by proxy, from his chaplain. It blamed the defeat on the unwillingness of the noble merchant galley captains, and collective funk: ‘all the merchant galleys, with the exception of the noble Vicenzo Polani, kept to windward and backed off … the whole fleet with one voice cried ‘Hang them! Hang them!’ … God knows they deserved it, but it would have been necessary to hang four fifths of our fleet.’ He reserved his special ire for the aristocratic

patroni

of the merchant galleys; ‘I’m not going to hide the truth in code … the ruin of our land has been the nobles themselves, at odds from first to last.’

Alvise Marcello wrote a highly self-serving account, blaming the confusion of the orders and depicting his own involvement in dramatic terms: he went alone into the melee and had his ship surrounded. ‘In the bombardment, I sent a vessel to the bottom with all hands; another came alongside; some of my men jumped aboard and cut many of the Turks to pieces. In the end I set fire to it and burned it.’ Finally with huge stone balls smashing into

his cabin, wounded in the leg, with his companions being mown down around him, he was forced to withdraw. Others were more scathing of this feat: ‘He went in and out, and said he’d taken a ship,’ muttered the chaplain. Domenico Malipiero, one of the few to emerge with his reputation unscathed, put much of the blame on Grimani’s confusions. The ordinary seamen believed that Grimani had sent Loredan to his death purely out of jealousy.