City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (4 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

It was the genius of Orseolo to fully understand that Venice’s growth, perhaps its very survival, lay far beyond the waters of the lagoon. He had already obtained favourable trading agreements with Constantinople, and, to the disgust of militant Christendom, he despatched ambassadors to the four corners of the Mediterranean to strike similar agreements with the Islamic world. The future for Venice lay in Alexandria, Syria, Constantinople

and the Barbary coast of North Africa, where wealthier, more advanced societies promised spices, silk, cotton and glass – luxurious commodities that the city was ideally placed to sell on into northern Italy and central Europe. The problem for Venetian sailors was that the voyage down the Adriatic was terribly unsafe. The city’s home waters, the Gulf of Venice, lay within its power, but the central Adriatic was a risky no-man’s-land, patrolled by Croat pirates. Since the eighth century these Slav settlers from the upper Balkans had established themselves on its eastern Dalmatian shores. This was a terrain made for maritime robbery. From island lairs and coastal creeks, the shallow-draughted Croat ships could dart out and snatch merchant traffic passing down the strait.

Venice had been conducting a running fight with these pirates for 150 years. The contest had yielded little but defeat and humiliation. One doge had been killed leading a punitive expedition; thereafter the Venetians had opted to pay craven tribute for free passage to the open seas. The Croats were now seeking to extend their influence to the old Roman towns further up the coast. Orseolo brought to this problem a clear strategic vision that would form the cornerstone of Venetian policy for all the centuries that the Republic lived. The Adriatic must provide free passage for Venetian ships, otherwise they would be forever bottled up. The doge ordered that there would be no more tribute and prepared a substantial fleet to command obedience.

Orseolo’s departure was marked by one of those prescient ceremonies that became a defining marker of Venetian history. A large crowd assembled for a ritual mass at the Church of St Peter of Castello, near the site of the present arsenal. The bishop presented the doge with a triumphal banner, which perhaps depicted for the first time St Mark’s lion, gold and rampant on a red background, crowned and winged, with the open gospel between his paws declaring peace but ready for war. The doge and his force then stepped aboard, and with the west wind billowing in their sails, surged out of the lagoon into the boisterous

Adriatic. Stopping only to receive further blessing from the bishop of Grado they set sail for the peninsula of Istria on the eastern tip of the Adriatic.

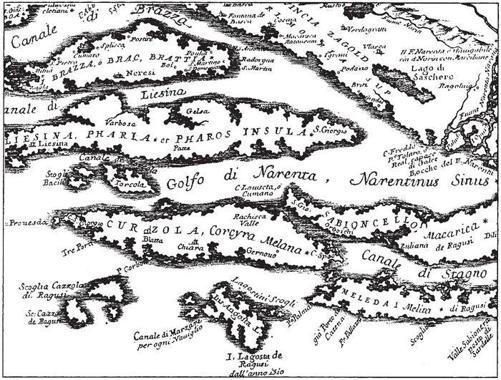

Orseolo’s campaign could almost serve as the template for subsequent Venetian policy: a mixture of shrewd diplomacy and the precise application of force. As the fleet worked its way down the small coastal cities – from Parenzo to Pola, Ossero to Zara – the citizens and bishops came out to demonstrate their loyalty to the doge and to bless him with their relics. Those who wavered, weighing Venice against the counter threat of the Slavs, were more readily convinced by the visible show of force. The Croats saw what was coming and tried to buy him off. Orseolo was not to be turned, though his task was made harder by the coastal terrain. The pirates’ stronghold was well protected, hidden up the marshy delta of the Narenta River and beyond the reach of any strike force. It was shielded by the three barrier islands of Lesina, Curzola and Lagosta, whose rocky fortresses presented a tough obstacle.

The Narenta River and its barrier islands

Relying on local intelligence, the Venetians ambushed a shipload of Narentine nobles returning from trade on the Italian shore and used them to force submission from the Croats at the mouth of the delta. They swore to forgo the annual tribute and harassment of the Republic’s ships. Only the offshore islands held out. The Venetians isolated them one by one and dropped anchor in their harbours. Curzola was stormed. Lagosta, ‘by whose violence the Venetians who sailed through the seas were very often robbed of their goods and sent naked away’, offered more stubborn resistance. The inhabitants believed their rocky citadel to be impregnable. The Venetians unleashed a furious assault on it from below; when that failed, a detachment made their way up by a steep path behind the citadel and captured the towers that contained the fort’s water supply. The defence collapsed. The people were led away in chains and their pirates’ nest demolished.

With this

force de frappe

, Orseolo put down a clear marker of Venetian intentions, and in case any of the subject cities had forgotten their recent vows, he retraced his footsteps, calling at their startled ports in a repeat show of strength, parading hostages and captured banners. ‘Thence, passing again by the aforesaid town, making his way back to Venice, he at length returned with great triumph.’ Henceforward, the doge and his successors awarded themselves a new honorific title – Dux Dalmatiae – lord of Dalmatia.

If there is a single moment that marked the start of the rise to maritime empire it was now, with the doge’s triumphal return to the lagoon. The breaking of the Narentine pirates was an act of great significance. It signalled the start of Venetian dominance of the Adriatic and its maintenance became an axiom for all the centuries that the Republic lived. The Adriatic must be a Venetian sea;

nostra chaxa

, they would say in dialect, ‘our house’, and its key was the Dalmatian coast. This was never quite straightforward. Over the centuries and almost until its last breath, the Republic would spend enormous resources fending off imperial interlopers, cuffing pirates and quelling troublesome vassals. The

Dalmatian cities – particularly Zara – struggled repeatedly to assert their independence but only Ragusa (Dubrovnik) ever managed it. Henceforward there was no rival naval power to match Venice in the heart of the sea. The Adriatic would fall under the political and economic shadow of an increasingly ravenous city, whose population would reach eighty thousand within a century. In time the limestone coast became the granary and vineyard of Venice; Istrian marble would front the Renaissance palaces on the Grand Canal; Dalmatian pine would plank their galleys and its seamen would sail them out of Venetian naval bases on the eastern shore. The crenellated limestone coast came to be seen almost as an extension of the lagoon.

The

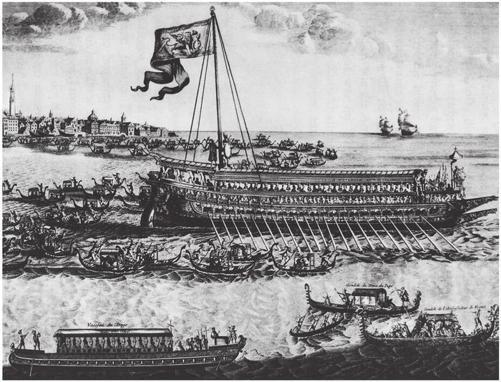

Bucintoro

and the Senza

The Republic, with a Byzantine talent for transforming significant victories into patriotic ceremonies, henceforth performed an annual celebration of Orseolo’s triumph. Every Ascension Day, the people of Venice participated in a ritual voyage to the

mouth of the lagoon. At the start it was a relatively plain affair. The clergy, dressed in their copes and ceremonial robes, climbed aboard a barge decked with golden cloth and sailed out to the

lidi

, the long line of sand bars that protects Venice from the Adriatic. They took a jar of holy water, salt and olive branches out to where the lagoon opens to the sea at the Lido of St Nicholas, the patron saint of sailors, and waited there, at the meeting of the two waters, for the doge to arrive in the ceremonial galley the Venetians called the

Bucintoro

, the Golden Boat. Rocking on the waves, the priests proclaimed a short and heartfelt prayer: ‘Grant, O Lord, that the sea is always calm and quiet for us and all who sail on it.’ And then they approached the

Bucintoro

and sprinkled water over the doge and his followers with the olive branches and poured the remainder into the sea.

In time the Ascension Day ceremony, the Senza, would become greatly elaborated, but in the early years of the millennium it was a simple act of blessing, a propitiation against storms and pirates, based on seasonal sailing rituals as ancient as Neptune and Poseidon. The miniature voyage enacted the whole meaning of Venice. Within the lagoon lay safety, security and peace; in its treacherous labyrinth of shallow channels all would-be attackers floundered and sank. Beyond lay opportunity but also danger. The

lidi

were the frontier between two worlds, the known and the unknown, the world that was safe and the one that was dangerous; in their founding myth St Mark was surprised by a squall and only found peace within the lagoon, but the voyage beyond was not optional. For the Venetians the sea was life and death and the Senza acknowledged the pact.

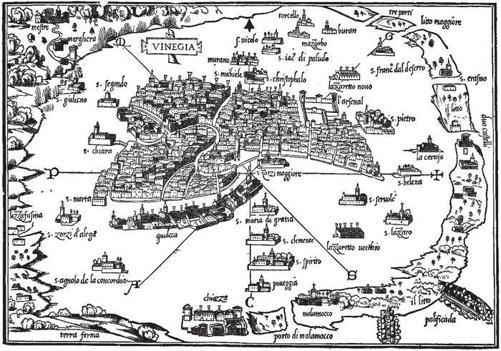

Venice sheltered by its

lidi

Ascension Day marked the start of the sailing season, when sailors could be hopeful of a calm voyage. Yet the waters of the Adriatic were notoriously fickle at any time of year. They could be smooth as silk, or whipped into choppy fury by the

bora

, the north wind. The Romans, no great sailors, were frightened of it; the Adriatic nearly drowned Julius Caesar, and the poet Horace thought there was nothing to equal the terror of the waves dashing

the cliffs of southern Albania. Oared galleys could be quickly swamped by a mounting sea; sailing ships running before the wind had little room for manoeuvre in the narrow straits. There is no more vivid historical account of the sea’s ferocity than the fate of a Norman fleet crossing to Albania in the early summer of 1081:

There was a heavy fall of snow and winds blowing furiously from the mountains lashed up the sea. There was a howling noise as the waves built up; oars snapped off as the rowers plunged them into the water, the sails were torn to shreds by the blasts, yard-arms were crushed and fell on the decks; and now ships were being swallowed up, crew and all … some of the ships sank and their crews drowned with them, others were dashed against the headlands and broke up … many corpses were thrown up by the waves.

The sea was tumultuous, dangerous, pirate-infested. The Venetians fought unceasingly to keep their seaway to the world open.

Even the

lidi

were no certain guarantee. Because the Adriatic is a cul-de-sac, it feels the moon’s tug with a special force, and when the phases are right and the sirocco, the wind from Africa, pushes

the water up the Venetian Gulf and the opposing

bora

, hard off the Hungarian steppes, holds it back, the lagoon itself is under threat. In folk memory, the events of late January 1106 emphasised the force of the sea. People remembered that the sirocco had been blowing up from the south with unusual force; the weather became unnervingly sultry, day after day sucking the energy out of men and beasts. There were unmistakable signs of approaching storm. House walls oozed moisture; the sea started to groan and gave off the strange neutral smell of electricity; birds skittered and squawked; eels leaped clear of the water as if trying to flee. When at last the storm broke, shattering thunder shook the houses and torrential rain hammered the lagoon. The sea rose up from its depths, overwhelmed the

lidi

, poured through the openings of the lagoon and swamped the city. It demolished houses, ruined merchandise, destroyed food stocks, drowned animals, strewed the small fields with sterile salt. An entire island, the ancient town of Malamocco, vanished, leaving ghostly foundations visible through the murky water at low tide. Hard on its heels came devastating fires that ripped through the wooden settlements, leaping the Grand Canal, incinerating twenty-four churches and gutting a major part of the city. ‘Venice was rocked to its very core,’ wrote the chronicler Andrea Dandolo. Venice’s hold on the material world was fragile; it lived with impermanence. It was against such forces that people felt their vulnerability and made sacrificial offerings.