City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (21 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

Despite the rhetoric, the sea which Venice mythologised, and the wealth that it carried, would prove harder won. The Genoese, excluded from easy access to rich trading zones, were snapping continuously at Venice’s heels. They waged an unofficial war of piracy against their maritime rivals. Three years before Doge Renier Zeno walked in the solemn Easter procession, an incident occurred in the crusader port of Acre on the shores of Syria: a Genoese citizen was killed by a Venetian. Three years later, the Mongols sacked Baghdad. In the aftermath of these disconnected events the two maritime republics would be drawn into a long-running contest for Mediterranean trade, which would lead them both to immense wealth and the edge of ruin. The arena would stretch from the steppes of Asia to the harbours of the Levant. It would encompass the Black Sea, the Nile Delta, the Adriatic, the Balearic Islands and the shores of Greece. Brawls would take place as far away as London and the streets of Bruges. Along the way all the peoples of the eastern Mediterranean would be caught up in its slipstream: the Byzantines, the Hungarians, rival Italian city states and the towns of the Dalmatian coast, the Mamluks of Egypt and the Ottoman Turks – all became entwined in the contest for their own advantage or defence. It would last 150 years.

Demand and Supply

1250–1291

Venezia e Genova

: Venice the Most Serene, Genoa the Proud. The two maritime republics were mirror images; even their names were echoes. Like Venice, Genoa, symmetrically positioned on the western flank of Italy at the top of its own gulf, was a natural point of trans-shipment from sea to land. It had easy access to the upper reaches of the Po valley and the wealthy markets of Milan and Turin, as well as routes through the Alpine passes into France. It too depended on the sea. Huddled about by mountains which offered plentiful wood for shipbuilding but no rich agricultural hinterland, Genoa looked to the Mediterranean as its escape from poverty and imprisonment. It had a good sheltered port and a climate more equitable than the malarial lagoon. Genoese sailors were as hardy as the Venetians, their merchants as avid for profit. Like their Adriatic rivals, the Genoese were pushy, pragmatic and ruthless.

In political temperament however they were quite different. Where Venetians submitted themselves to government control and worked by communal enterprise, born out of the city’s precarious physical position, the need for co-operation to prevent its islands from being flooded and its lagoon silting up, the Genoese were marked by a strong streak of individualism and a preference for private enterprise. It was a distinction not lost on unsympathetic outside observers. In an analogy unflattering to both peoples, the Florentine Franco Sacchetti likened the Genoese to donkeys:

Genoa

The nature of the donkey is this: when many are together, and one of them is thrashed with a stick, all scatter, fleeing hither and thither, so great is their vileness … The Venetians are similar to pigs and are called ‘Venetian pigs’, and truly they have a pig’s nature, for when a multitude of pigs is confined together and one of them is hit or beaten with a stick, all draw close and run unto him who hits it; and this is truly their nature.

It was out of these contrasts in character that a fierce commercial rivalry would develop.

Genoa shared the same goals as Venice: to grab share and monopolise markets, but its means were different. From the start the Genoese maritime empire was largely privatised – the fleet that beat the more cautious Venetians to the First Crusade and gained preferential trading rights in the new crusader kingdom was got up by individual initiative. Intrepid Genoese risk-takers staked claims earlier and adopted technologies faster. Genoa was the first to many of the commercial and practical innovations that

revolutionised international trade. Gold currency, marine charts, insurance contracts, the use of the stern rudder, the introduction of public mechanical clocks – the Genoese were using these decades earlier than the Venetians. Having gained a head start in the Levant trade during the First Crusade, Genoa initiated a lucrative galley route to Flanders fifty years before Venice and notwithstanding the singular fame of Marco Polo pushed faster and further into the Orient than their Adriatic rivals. Facing west towards the Atlantic gave the Genoese an amplified sense of the possibilities beyond the Mediterranean basin and better access to ocean-going ship technologies. As early as 1291 two Genoese brothers sailed out of the Gates of Gibraltar to seek a route to India. It was no accident that it should be the Genoese sailor Christopher Columbus (Cristóbal Colón) who touched the New World in 1492. Intrepid, creative, risk-taking, innovative – these were hallmarks of the individualistic genius of Genoa.

It was also characteristic that one of Columbus’s prime objectives in crossing the Atlantic was to find a fresh stock of human beings to enslave. Linked to this energetic individualism was a dark side to the Genoese temperament. The ruthless materialism of the Italian maritime republics, their ‘insatiable thirst for wealth’ commented on by Petrarch, startled and repulsed the pious medieval world. Both were frequently castigated by the papacy for trading with Islam; the Byzantines found them odious and the Muslims despised them. But if Pope Pius II thought the Venetians were hardly further up the scale of nature than fish, and the words ‘Venetians’ and ‘bastards’ sounded identical to Syrian Arabs, Genoa generally enjoyed a slightly worse reputation: ‘cruel men, who love nothing but money’ was the curt judgement of one Byzantine chronicler. They were enthusiastic slavers – there were more slaves in Genoa than any other city in medieval Europe. The Genoese also had a fatal weakness for chaotic violence; the internal politics of the city were riven by repeated bouts of factional infighting so exhausting that the people periodically begged outsiders to govern the city; it was an object lesson in

political instability that made the prudent Venetians shudder. On the high seas they acquired a similar notoriety for piracy and privatised plunder. For Genoa there was a particularly thin line between warfare and buccaneering.

Like the Venetians they were everywhere; by the start of the fourteenth century Genoese traders could be found from Britain to Bombay, establishing trading posts, shifting cargoes by camel or mule train, packing spices into ships, buying and selling wheat and silk and grain. ‘So many are the Genoese,’ wrote a patriotic city poet, ‘and so spread out throughout the world, that wherever one goes and stays, he makes another Genoa there.’ By 1250, Genoa was booming; its population, about fifty thousand, was one of the largest in Europe, though always smaller than that of Venice – and furiously competing for the goods of the world.

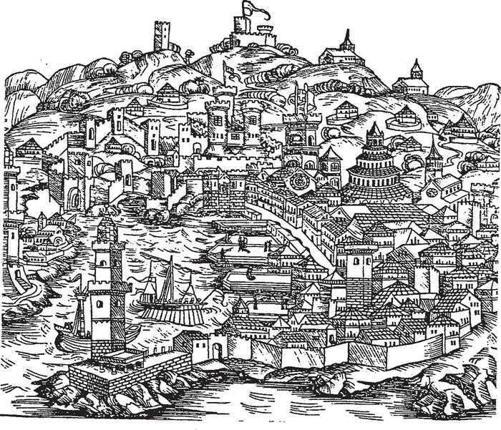

The contest with Venice – and its other close rival Pisa – had started with the opportunities of the early crusades. All the Italian maritime republics aspired to be monopoly traders, keen to lock out competitors and to strike exclusive deals with the host lords of the Levant. The quarrelsome merchant settlements, frequently barricaded in adjacent quarters like miniature forts, made tiresome guests. Nowhere was this more marked than in Constantinople where the bickering between rival colonies drove the Byzantine emperors to call a plague on all their houses and periodically to expel the lot.

Everything changed after 1204. The fall of Constantinople gifted the Venetians a dominant position. At a stroke the Genoese were excluded from some of the richest markets of the east. Venice controlled the Aegean, gained a first foothold in the Black Sea, won Crete – and above all was co-owner of Constantinople. For Genoa it represented a huge setback. Its privateers harried the triumphant Venetians wherever they could; Henry the Fisherman made a bold grab for Crete; Genoese pirates methodically began to plunder Venetian merchant fleets as an alternative form of war. The great wave of prosperity that Venice experienced in the half-century after 1204 intensified profound jealousy elsewhere

where in the Mediterranean. It exploded into open warfare in the crusader port of Acre on the shores of Syria.

Here, in a dense walled town with its encircling harbour, the two republics occupied adjoining colonies and competed fiercely for lucrative trade with the Islamic world. For Genoa, Acre and its adjoining port of Tyre, represented a heartland: they had established a presence here earlier than Venice and they looked to establish a compensating monopoly for Venetian control of Constantinople. The atmosphere was heavy with commercial rivalry. In 1250 an incident took place in Acre that led to a riot; the riot became a battle, and the battle provoked a war that would spread across the whole of the eastern Mediterranean.

The causes were small but multiple. There was a dispute over a shared church that lay between the two mercantile quarters; a Genoese seaman turned up in the harbour with a ship which the Venetians, with their suspicious eye for piracy, thought was one of theirs taken by theft; a private quarrel between two citizens turned into a fight that left the Genoese dead. At a certain temperature the powder keg exploded. A Genoese mob descended on the harbour and sacked Venetian ships, then pillaged their quarter and slaughtered its inhabitants.

When word got back to Venice, the doge demanded satisfaction. Not getting it, the Venetians armed thirty-two galleys under Lorenzo Tiepolo, the son of a former doge, and sailed off to the Levant. In 1255, Tiepolo’s fleet hove into view off Acre, crashed through the chain which the Genoese had strung across its mouth and burned their galleys. Descending on the nearby stronghold at Tyre, the Venetians redoubled the humiliation, capturing the Genoese admiral and three hundred citizens who were transported back to Acre in chains. The town became a cauldron of street violence, split down the middle and sucking all the other resident nationalities into the contest. Both sides used heavy siege equipment to bombard rival fortifications. The Venetians sent for more ships from Crete; ‘every day the contest was fierce and bitter’, according to the Venetian chronicler Martino

da Canal. When news reached Genoa of their citizens being led through Acre in chains, there was an outpouring of patriotic fury: ‘there were calls for vengeance such as have never been forgotten. Women said to their husbands: “Spend our dowries on revenge.”’ Both sides fed in more ships and men, but the Venetians managed to press forward street by street, taking the contested church and a key hill within the town. The Genoese were forced back to their bazaar area. It was a bitter, slow-motion contest – the foretaste of things to come.

Back in Genoa and Venice new forces were enrolled. In 1257 the Genoese despatched a larger fleet of forty galleys and four round ships under a new admiral, Rosso della Turca. Getting wind of this, the Venetians hurried out matching ships of their own under Paolo Faliero. In June, della Turca’s fleet showed up off the Syrian coast to the immense joy of the beleaguered Genoese. From a tall tower in their quarter they hung the banners of all their allies in the fight and made a triumphant din, raining down insults on the Venetians below; in the colourful (and prejudicial) words of the Venetian chronicler: ‘Slaves, you’re all going to die! … flee the city that will be your death. Here comes the flower of Christianity! Tomorrow you will all be killed, either on sea or land!’

Della Turca’s fleet bore down on Acre for a definitive collision. As they approached, the ships lowered their sails and dropped anchor to threaten the harbour. The wind was too strong for the Venetian ships to sally forth. Night fell and the Genoese in the town ‘made great illuminations with candles and torches … They were so emboldened and made such great boasting and such a din that the most mild-mannered seemed like a lion, and they continually threatened the Venetians.’

Next morning at dawn, both sides prepared themselves for the inevitable sea battle. The Venetian commanders attempted to put spirit into their men with a singing of the Evangelists’ psalm. ‘And when they had sung, they ate a little and then they weighed anchor and roared, “Pray for us with the help of our Lord Jesus

Christ and St Mark of Venice!” And they began to row forward.’ Back in the town the Genoese garrison sallied out to confront the Venetian

bailo

[governor] and his men. Cries of ‘St Mark!’ and ‘St George!’ rang across the sea as the two fleets closed, with the gold lion of Venice and the flag of Genoa – a red cross on a white background – fluttering in the wind, ‘and the battle on the high sea was huge and extraordinary, hard fought and bitter’. The Genoese had slightly the larger fleet but the Venetians had hired extra men from the mixed populations of Acre. It was to be the first of many maritime encounters and it ended with a ringing Venetian victory. The Genoese hurled themselves into the sea or turned their ships in flight; the Venetians took twenty-five galleys, 1,700 men drowned in the sea or were taken. Seeing the annihilation of their fleet, the Genoese garrison laid down its arms and surrendered, and the crusader knight Philip de Montfort, coming up the coast from Tyre to help the Genoese, turned back in disgust at the spectacle with the remark that ‘the Genoese are empty boasters who more resemble seagulls, diving into the sea and drowning. Their pride has been laid low.’ The Genoese lowered the flags on their tower and surrendered. They were expelled from Acre; their tower was razed to the ground; chained prisoners were paraded in St Mark’s Square and confined to the dungeons of the doge’s palace. It took the pleading of the pope to secure their release. As a souvenir, the Venetians also carried home from their enemy’s quarter the squat stump of a porphyry column which was set up in St Mark’s Square at the corner of the church. It became known as the Pietra del Bando, the proclamation stone, from which the laws of the Republic were read out, and on which the freshly severed heads of traitors who broke them were put on display. (‘The smell of them’, one later visitor complained, ‘doth breed a very offensive and contagious annoyance.’)