Citizen Emperor (34 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

Jean Bertrand Andrieu,

Alliance avec la Saxe

(Alliance with Saxony), 1806. The medal shows the profiles of the Emperors Napoleon and Charlemagne.

c RMN-Grand Palais (Sevres, Cite de la Ceramique/Martina Beck-Coppola

The idea of Charlemagne was pressed home in a newspaper campaign that took place shortly before the proclamation of the Empire,

98

but it had been present almost as soon as Bonaparte became a public figure.

99

Admittedly, the output of pamphlets and books was not impressive – and it does not seem to have inspired the popular imagination – but the message was clear, especially since the idea of Charlemagne was meant to be flexible enough to appeal to both republicans and royalists.

100

Some of the material, therefore, was written with republicans in mind. In these writings, Napoleon represented the republican ideal, a meritocratic system in which anyone could become anything. According to the official line, the title of emperor was to serve the interests, the wellbeing and the glory of the nation, and had nothing to do with the personal interests of Napoleon.

101

It was, once again, a question of ‘curbing all factions, bringing together all parties and erasing even the memory of the former divisions’.

102

‘The Restorer of the Roman Empire’

Bonaparte had been thinking of Augustus.

103

The idea of officially associating Napoleon with the reign of Charlemagne belonged to Louis Fontanes. In September 1804, in order to make the association clearer, Napoleon paid a visit to Aachen, the city in which Charlemagne was crowned in the year 800, and where his memory was still very much alive.

104

Officially, Napoleon’s visit was to be a tour of the four departments of the Rhine, but he was also to receive the homage of a number of Germanic princes. While there, he took part in a procession in which what were believed to be the relics of Charlemagne (the skull and an arm) were ceremoniously carried to the cathedral, where he stood before what contemporaries believed to be Charlemagne’s resting place.

105

We now know the relics were bogus, but the gesture was nevertheless pregnant with symbolic meaning. Aachen was a kind of pilgrimage, a nod in the direction of a national hero, once emperor of the western world. But Napoleon was also testing the waters. Meeting with the Germanic princes was a way of measuring princely opinion (Charlemagne had also received the German princes at Mainz on his way to Rome to be crowned emperor). Napoleon went on to visit a dozen or so other cities as he wound his way down the Rhine to Mainz, a sort of

Via triumphalis

, as his new subjects turned out to greet the imperial couple; crowds got bigger the closer they got to Mainz. At a reception in Mainz on 21 September, he held court (for the first time outside Paris), and more or less received homage from most of the German princes while he did his best to charm them.

106

This was designed partly to counteract the effects of the Enghien affair, and partly to bring the German princes onside in the lead-up to another war. The German princes may have made a choice based on Realpolitik, but German intellectuals and republicans were far more circumspect, if not disillusioned by Napoleon’s decision to adopt the imperial mantle.

107

He had betrayed his revolutionary roots; for

ancien régime

nobles, he could never be anything more than an upstart.

The Thaumaturge King

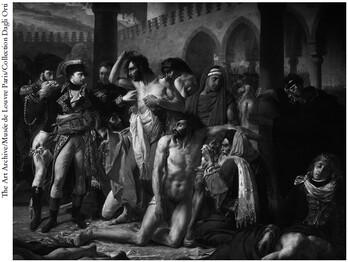

In keeping with the drive to portray Napoleon as monarch, artists were also enlisted. The highlight of the Salon of 1804, measuring five metres by seven, was Gros’

Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa

.

108

The painting’s public and critical reception at the Salon that year was enthusiastic. A secret police bulletin reported that all classes of society had been ‘moved’ by the painting.

109

It was helped by the fact that the memory of the expedition to Egypt was still fresh in people’s minds. The artist, Antoine-Jean Gros, later recounted that when the doors of the studio in which the painting was executed, the former Jeu de Paume in Versailles, were closed shortly before its transfer to the Louvre, a crowd of workers gathered outside and begged him, money in hand, to be allowed to see it.

110

One witness recalled that ‘the sincere admiration which this composition excited was so general that painters from all the respected schools united to carry to the Louvre a great laurel wreath to hang above Gros’s picture’.

111

The press described it as the greatest success of the Salon.

112

Two aspects of the paintings are worth dwelling on. The first is that it portrays the French army in defeat, or at least decimated by the plague. The scene is one of dire misery in which the arrival of the saviour – Bonaparte – appropriately recognized by the light cast on him in contrast to the dark shadows that engulf the dying, illuminates the whole and brings the promise of healing. The real subject of the painting is, after all, not so much the army as Bonaparte as active hero who extends his hand in a Christ-like gesture to heal a victim of the plague, as if in the royal tradition his touch could heal the sick. At the same time, both Arab and French medical personnel are busy around him trying to stem the tide of death. The contrast between light and darkness is meant as a metaphor to highlight Bonaparte’s supernatural qualities. Bonaparte gives life, an image mirrored in a poem that appeared a year later in the

Mercure de France

, ‘L’Hospice de Jaffa’ (The hospital at Jaffa), in which Napoleon appears on a chariot accompanied by both Glory and Humanity to bring light and life.

113

The failure of the Syrian expedition was thus transformed through Bonaparte’s glamorous gesture into a victory, of sorts.

114

This painting is not only another element in the construction of the Napoleonic legend, it was meant to provide an alternative vision to the rumours about Bonaparte’s order to poison plague victims at Jaffa.

115

This rumour reached France through the returning army,

116

as well as appearing in the clandestine publications that circulated. In 1802, for example, Robert Wilson published an account of the Egyptian and Syrian campaigns that accused Bonaparte of having massacred the prisoners at Jaffa and of having poisoned sick French troops.

117

It seems to have gained wide currency, even if it was dismissed by most supporters of the regime as simply British propaganda.

118

Placed between Bonaparte and the plague victim whose arm is raised so that his bubo can be examined is Nicolas René Desgenettes, the very man whose criticism of Bonaparte’s policies towards the plague helped fan the rumours about poisoning in the first place. His inclusion was a clear attempt to negate those rumours by associating him with Bonaparte’s gesture.

119

A man who might be Berthier has his arm around Bonaparte’s waist as if to hold him back from the victim, while pressing a handkerchief against his face. The gesture is repeated by General Jean-Baptiste Bessières, who was with Bonaparte in Egypt, hardly discernible in the shadows behind Berthier. Bonaparte’s face, on the other hand, is uncovered, as though he were immune to the stench. The Turk, a local Christian, who is kneeling to cut a bubo is based on an actual character: he was almost always drunk but was considered to be a local specialist in the disease. Desgenettes often saw him dragged from an alcohol-induced sleep and led, or sometimes driven by a baton, into the hospital where, without any precaution, he would incise the buboes, wipe his bistoury or surgical knife and then replace it between his forehead and his turban. The doctor who has succumbed to the plague in the right-hand corner is probably a man by the name of Saint-Ours who did die at Jaffa. He represents the many medical personnel who died of the plague during the Syrian campaign. Finally, just above Saint-Ours is a man suffering from what was commonly referred to as ophthalmia (a general term used to describe several kinds of conjunctivitis), who is trying to grope his way towards Bonaparte, an image inspired no doubt by the biblical gesture of the blind man at Jericho.

If the painting is clearly meant to counter the poison rumours, it can also be interpreted as part of the tradition of the thaumaturge king.

120

The anointed kings of France would appear outside the cathedral at Rheims and demonstrate the miraculous character of their office – the king’s body being rendered sacred by the anointing ceremony – by laying hands on the sufferers of scrofula. It meant that people were allowed to touch the king’s mantle, or at least its hem. The practice was discontinued under Louis XV, but was revived under Louis XVI.

121

Napoleon could not renew this practice, but we see the idea of the king’s sacred body reintroduced in Gros’ painting, albeit elliptically, so that for the first time the dignity of the citizen and that of the monarch are combined to form a new amalgam, the dignity of the citizen-monarch.

Detail of Antoine-Jean Gros,

Bonaparte visitant les pestiférés de Jaffa

(Bonaparte visiting the plague victims at Jaffa), 1804. It is an image, as one historian has put it, of ‘Christ in a republican uniform’.

122

That interpretation is contested, but it certainly shows Napoleon as the ‘caring father’, in the tradition of the clement ruler (about which more below).

123

Moreover, the painting’s political message is ambiguous.

124

An alternative interpretation is the use of illness as a metaphor to describe the sickly French body politic.

125

Gros quite possibly thought in terms of metaphor – Bonaparte arriving as saviour to heal a sick, faction-ridden France. Moreover, the plague was often associated with political upheaval, an expression of anarchy, literally a ‘pest’.

126

Gros’ painting, therefore, represents the ravaged body politic, portrayed by French soldiers languishing in various postures. An alternative to chaos and death is presented to the onlooker – the uniformed soldier, in the form of Bonaparte and his generals. The logical conclusion is that allegiance to Napoleon was the only alternative to the dissent and factionalism that had riven French society.

Rendering Napoleon Sacred

And that was the message driven home time and again by the regime: namely, just as Brumaire was necessary to bring all Frenchmen together, so too was the Empire designed to heal the festering social and political wounds of the Revolution. The crowning moment of this campaign was to be a religious ceremony in the Cathedral of Notre Dame designed to impress the people of Europe and at the same time lend weight to Napoleon’s claim to the throne.

Once again, Louis Fontanes seems to have had the idea for a religious coronation, although it did not go down well with everyone.

127

Comte Jean-Baptiste Treilhard in the Council of State, for example, questioned the need for it. He was among a number of politicians who preferred a civil ceremony on the Champ de Mars, to be put off till the following year.

128

For most in the Emperor’s entourage, however, the political symbolism of a religious ceremony was understood. Fontanes, for example, suggested that Napoleon adopt the pomp traditionally associated with the kings of France, urging him not to neglect the religious elements of the

sacre

(consecration).

129

As Jean-Etienne-Marie Portalis, later to become director of religious affairs, pointed out to Napoleon, ‘anything that renders sacred the person who governs is a good thing’.

130

Contemporaries were well aware, in other words, that the ceremony was about constructing an appearance of legitimacy through the use of tradition, costume and symbolism.