Citizen Emperor (102 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

23

‘I Shall Know How to Die’

Napoleon left for the army on 25 January 1814 at three in the morning.

1

A proclamation issued by the Paris municipal council a few days beforehand appealed to patriotic sentiment. ‘Who would not shed his blood to preserve inviolate the honour we hold from our ancestors to keep France within her natural frontiers?’ the proclamation asked.

2

Not many it would seem, since desertion was at an all-time high. The reaction in Paris to a foreign invasion was one of dread – ‘Everyone is looking at each other as though they were travellers in danger of sinking. Everyone is packing; hiding what he has of value’

3

– but there was little popular support for the regime, something that can in part be explained by the dire economic straits of the working classes of Paris (in particular).

4

Things at first did not go well for the allies, despite superior numbers

5

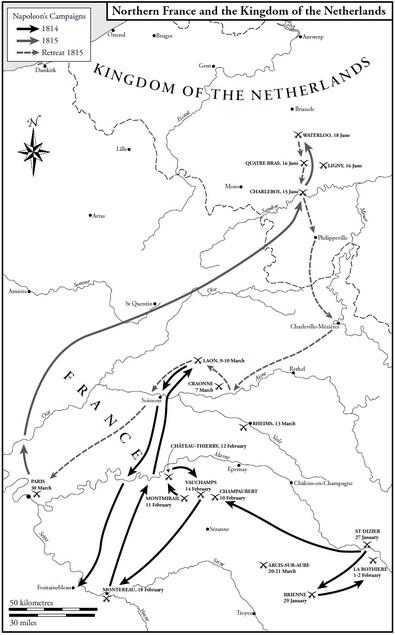

– in the north-east Napoleon had about 70,000 troops facing 200,000 allied troops. Battles were fought at Brienne (29 January), where Blücher was forced to withdraw, and La Rothière (1 February), where Napoleon was outnumbered by two to one. Despite knowing of this disparity, Napoleon was nevertheless forced to engage, hoping to hold off the enemy until he could withdraw under cover of darkness. The bad weather – snow fell during the battle, reducing visibility – helped him mask the extent of his weakness as well as obliging the allies to concentrate their attack on the village of La Rothière. It changed hands three times in the course of the battle, until Napoleon decided to withdraw in good order at the end of the day’s fighting with the loss of 5,000–6,000 men, less than the number of allied losses (8,000–9,000 men).

6

Nevertheless, the tactical withdrawal at La Rothière was a moral victory for the eastern powers and a blow to Napoleon’s own troops. The second battle of the campaign for France had been lost by Napoleon, and troops deserted in droves in the days that followed. ‘The Paris road was covered with soldiers of all arms,’ wrote one officer, ‘especially of the Young Guard. As an excuse to leave the army, they said they were ill or wounded.’

7

The defeat also shocked Paris when news filtered through. It reignited Alexander’s desire to march on the capital, to overthrow Napoleon and to replace him with a king of his own choosing.

8

At this stage, the Tsar seriously contemplated withdrawing Russian troops from Schwarzenberg’s Army of Bohemia, combining them with Blücher’s Army of Silesia, where the bulk of Russian troops were anyway, and, together with the Prussians, marching on Paris.

9

Then news arrived that Murat in Italy had defected to the allies.

10

Incited by the Emperor’s own sister, Caroline, Murat betrayed Napoleon by joining the coalition in the hope of saving his own crown, a move Napoleon described as ‘without name’.

11

Once again, however, the Emperor’s military acumen came to the fore. After Brienne and La Rothière he withdrew to Troyes, where he got a rather sullen reception from the local population, and placed his troops behind the Seine, whence he hoped to muster fresh troops and win a little time before relaunching the offensive. It was while he was at Troyes that he learnt the allies had committed the mistake of splitting their army, with Blücher marching on Châlons and Schwarzenberg on Troyes.

Every battle fought was somehow an opportunity, in Napoleon’s mind, for a knockout blow that would end the war. He wrote to Joseph along those lines on 13 February: ‘If this operation is successful, we may very well find the whole campaign decided.’

12

It was wishful thinking. His men were mostly raw recruits who had had to live in open country under the rain, who had not eaten properly for days and who were outnumbered by the allies. Even so, he fought and defeated the allies at Champaubert (10 February), Montmirail (11 February), Château-Thierry (12 February) and Vauchamps (14 February), sending the allies into a disorderly retreat. He then turned south and on 17 February attacked an already retreating Schwarzenberg at Nangis and Mormant. It is astonishing under the circumstances just how well Napoleon and his men performed. For the allies, it brought back memories of previous defeats. For Napoleon, it gave him unfounded hope that victory was possible, and made him intractable when the allies offered preliminary peace terms. The outcome of each battle was grossly exaggerated – after Montmirail he wrote Joseph to say that the Army of Silesia was no more.

13

It was hardly the case. Another battle was fought and won against Schwarzenberg at Montereau on 18 February in which the allies lost some 6,000 casualties to the French 2,500. In the space of a week, the Prussian army had lost considerable ground and about 20,000 men.

But this was a different kind of campaign. Napoleon did not have control over its direction, was greatly outnumbered and was sometimes obliged to fight when he did not want to. Even if he had managed to push the allied troops back across the Rhine, as he had hoped, it would only have delayed the inevitable. This was not the first Italian campaign. Napoleon’s victories were small affairs that could not decide the outcome of the campaign. Certainly, they deflated Alexander’s ego and threw the minor German allies into a panic, even forcing a partial allied withdrawal, but they could not end the war.

14

More importantly, with every victory Napoleon lost men he could ill afford to lose whereas the allies had the vital depth of resources and now the resolve not to admit defeat. After each victory, Napoleon would use the same methods that he had used to celebrate his victories in the past: flags were dispatched to Paris; the regulation thirty cannon salvoes were fired; sometimes prisoners were sent as trophies.

It made little impact. After news of La Rothière had reached Paris, a small panic set in that lasted a good week; people rushed to the banks to get out their money, a great many shops shut, and people started hoarding provisions as if for a siege.

15

Royalists came out of the woodwork and started putting up placards on the walls of towns throughout France either announcing the return of Louis XVIII or issuing proclamations in his name.

16

The general despondency was so obvious that Cambacérès warned Napoleon that the most ‘sinister events’ would occur if he did not quickly come to the aid of Paris.

17

In the capital, the prefecture of police was receiving up to 1,300 requests a day for passports that would allow their holders to leave the city.

18

Even Letizia, apparently afraid of what would happen if Paris were besieged, asked her daughter-in-law to warn her if ever she decided to leave, so that she could go with her.

19

At the same time, hordes of people from the surrounding countryside were attempting to find refuge in Paris. That is perhaps why, when news of the victories started to come in – this is the bulletin of Champaubert – there was a general sense of relief, not to say of hope. After news of victory at the battle of Château-Thierry on 12 February was announced, a crowd gathered before the Tuileries to acclaim Marie-Louise and the three-year-old King of Rome, who appeared in the uniform of the National Guard.

20

(The previous month, Napoleon had called 900 officers of the National Guard to the Tuileries and entrusted them with the Empress and their son.)

21

Blücher did not care what his supreme command was doing, or Napoleon for that matter. He was on the march and was heading straight for Paris. Napoleon had to react. He was in Troyes at the time and turned back at the head of the Guard to meet up with troops under Ney and Victor. He finally caught up with Blücher on 7 March at Craonne, about thirty kilometres north-west of Rheims. Once again, despite overwhelming odds – around 85,000 Russian and Prussian troops faced 37,000 French – Napoleon was able to inflict a defeat, although for the loss of about 5,400 men.

22

In terms of the percentages killed and wounded – one in four men involved in the battle – it was one of the bloodiest battles of the campaign.

23

The Prussians blamed the Russian General Wintzingerode for moving too slowly to come to Blücher’s assistance, believing that they had missed an opportunity to defeat Napoleon.

24

Napoleon was obliged to fight them again two days later at Laon, twenty-odd kilometres further north, again against overwhelming odds. Blücher had around 100,000 men and 150 cannon while Napoleon possessed only around 40,000 troops. Napoleon was let down by the lacklustre performance of Marmont, as he had been on a number of occasions during the campaign by his marshals. It was in any event a stroke of good luck for the French Emperor that Blücher fell ill, probably overcome with exhaustion, so that he could not personally direct operations. At the end of the second day’s fighting, Napoleon was able to extricate himself and withdraw towards Soissons, but the encounter had cost him another 6,000 casualties (to the allies’ 4,000). Soissons was only about a hundred kilometres from Paris. And yet Napoleon fought on. What else could he do? Seeing another chance to defeat the allies at Rheims where they had extended their lines, Napoleon turned east, reaching the outskirts of the town late in the afternoon of 13 March, when darkness had already fallen. He had managed to catch a couple of hours’ sleep when the Russians decided on a night attack at around 10 p.m. It was a mistake; Napoleon took the town two hours later with a few thousand allied casualties to 700 French.

The victory went to his head, reinforcing the notion that he was still the man of Austerlitz. He was not, but it was the man of Austerlitz the allies feared. The victory at Rheims, minor as it was, sent them into a tizz and they began to retreat again. This does not mean that Napoleon had a chance of defeating them – on the contrary. When Caulaincourt realized that the allied sovereigns were in a panic, he persuaded Napoleon to accept the 1792 frontiers as terms for negotiations, but his plenipotentiaries were not allowed to pass through the lines. The allies had met at Chaumont, a ‘dirty and dull town’ about 240 kilometres south-east of Paris, and signed a treaty on 9 March, a twenty-year quadruple alliance, which set out their determination to defeat Napoleon, to return France to its pre-revolutionary borders, to bring about a general peace in Europe and to convene an international congress to discuss any outstanding issues. Castlereagh was crucial in getting the allies to agree to stipulate their common goals.

25

Napoleon’s decision to fight on and his refusal to negotiate meant that, some time in the last week of March, the allies resolved to remove him from the throne. There were to be no further negotiations; this was a fight to the finish.

Besides, they did not retreat for long. Schwarzenberg decided to halt and face Napoleon, something that took the Emperor completely by surprise. At Arcis-sur-Aube (20 March), Napoleon again faced far superior forces – about 28,000 French up against 80,000 allied troops – although he was under the mistaken impression that he was dealing only with the allied rearguard. The allies were dispersed around the exposed, low-lying town of Arcis, pounding it with artillery fire. Napoleon threw himself into the thick of it. At one point, he rode his horse over a smoking howitzer shell, which then exploded, disembowelling and killing the horse. ‘He disappeared in the dust and smoke. But he got up without a scratch, and mounting a new horse rode off to inspect the positions of the other battalions.’

26

Did he want to impress his troops, to show his men that he was not afraid of death; was he, as one historian has suggested, attempting to place his horse between himself and the explosion; or did he want to end it all? It is, of course, impossible to say.