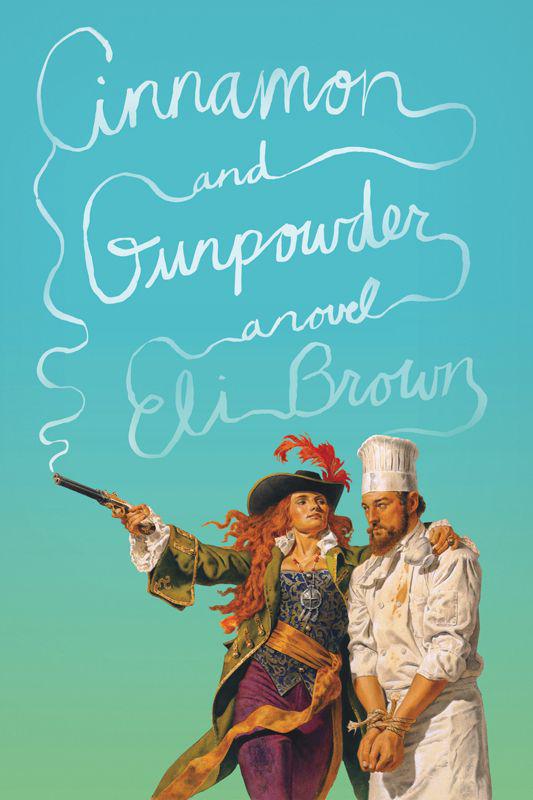

Cinnamon and Gunpowder

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

FOR DAVON,

who picked me up and dusted me off

“I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.”

—

CAPTAIN AHAB

, Herman Melville,

Moby-Dick

CONTENTS

| | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| |

1. | |

| | In which I am kidnapped by pirates |

2. | |

| | In which I am bent to new employment |

3. | |

| | In which I receive valuable advice from a mysterious friend and witness an execution |

4. | |

| | In which I make contact with a fellow prisoner |

5. | |

| | In which I vow to stop Mabbot |

6. | |

| | In which I earn a pillow |

7. | |

| | In which I am rescued by an unlikely ship |

8. | |

| | In which I am entertained by the King of Thieves |

9. | |

| | In which many are punished |

10. | |

| | In which cabbages and history are mistreated as we cross the equator |

11. | |

| | In which Mabbot reveals herself |

12. | |

| | In which we are bitten by the Fox |

13. | |

| | In which justice catches up with us |

14. | |

| | In which I lose much |

15. | |

| | In which we lick our wounds and Joshua tells his story |

16. | |

| | In which Mabbot surprises me and I receive a gift |

17. | |

| | In which we visit a witch |

18. | |

| | In which I am misunderstood |

19. | |

| | In which trust is betrayed |

20. | |

| | In which I see my error |

21. | |

| | In which I attempt a final escape |

22. | |

| | In which Mabbot’s hunt ends |

23. | |

| | In which a sacrifice is accepted |

24. | |

| | In which I discover the saboteur |

25. | |

| | In which the sea boils |

26. | |

| | In which I fight for Mabbot |

| | |

| |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| |

1

DINNER GUESTS

In which I am kidnapped by pirates

Wednesday, August 18, 1819

This body is not brave. Bespeckled with blood, surrounded by enemies, and bound on a dark course whose ultimate destination I cannot fathom—I am not brave.

The nub of a candle casts quaking light on my damp chamber. I have been afforded a quill and a logbook only after insisting that measurement and notation are crucial to the task before me.

I have no intention of cooperating for long; indeed, I hope to have a plan of escape soon. Meanwhile, I am taking refuge in these blank pages, to make note of my captors’ physiognomy and to list their atrocities that they might be brought properly to justice, but most of all to clear my head, for it is by God’s mercy alone that I have not been driven mad by what I have seen and endured.

Sleep is impossible; the swells churn my stomach, and my heart scrambles to free itself from my throat. My anxiety provokes a terrible need to relieve myself, but my chamber pot threatens to spill with every lurch of this damned craft. I use a soiled towel for my ablutions, the very towel that was on my person when I was cruelly kidnapped just days ago.

To see my employer, as true and honest a gentleman as England ever sired, so brutally murdered, without the opportunity to defend himself, by the very criminals he had striven so ardently to rid the world of, was a shock I can hardly bear. Even now my hand, which can lift a cauldron with ease, trembles at the memory.

But I must record while my recollections are fresh, for I cannot be sure that any of the other witnesses were spared. My own survival is due not to mercy but to the twisted whimsy of the beast they call Captain Mabbot.

It transpired thus.

I had accompanied Lord Ramsey, God rest his soul, to Eastbourne, the quaint seaside summer home of his friend and colleague Mr. Percy. There we rendezvoused with Lord Maraday, Mr. Kindell, and their wives. It was not a trivial trip, as the four men represented the most influential interests in the Pendleton Trading Company.

I had been in his lordship’s employ for eight years, and it was his habit to bring me along on journeys, saying, as he did, “Why should I suffer the indignities of baser victuals in my autumn years when I have you?” Indeed, it had been my honor to meet and cook for gentlemen and ladies of the highest stature, and to have seen the finest estates of the countryside. My reputation grew in his service, and I have been toasted by generals and duchesses throughout England. Happily for me, his lordship rarely went overseas, and even on those occasions he left me in London, respecting my considerable aversion to the rolling of ships.

This particular trip had me at my most vigilant, not only due to the prominence of the guests but because the Percy seat was reportedly rustic, of unknown appointment, and sporting a historic oven without proper bellows or ventilation. Try as I did, I could not acquire reliable information as to the status of the pantry prior to arrival. For this reason I provisioned myself with a menagerie of ducks, quail, and a small but vociferous lamb, as well as boxed herbs and spices, columns of cheeses, and my best whisks and knives. Lord Ramsey teased that I had packed the entire kitchen. But I could see in his face satisfaction at my diligence. His faith in me was a poultice for my nerves. As usual, I had worried myself sleepless over the event. The modest size of the house prevented me from bringing my able assistants—a stroke of luck for them, as they are safe now in London. Rather, I relied wholly on the staff brought by the other guests.

Eastbourne was as lovely as I had heard, with foals cavorting in the pasture and the woods promising moss-cushioned idylls. The house itself commanded stunning views of the channel, an azure scarf embroidered with sails and triumphal clouds. As it happened, both pantry and scullery maids were more than adequate. While I always prefer my kitchen at his lordship’s seat in London—every inch of which I have organized, from the height of the pastry table to the library of spices catalogued both by frequency of use and alphabetically—I nevertheless took pleasure in anointing a new kitchen with aromas.

With great energy I oversaw the unpacking of my provisions and set a scullery maid to heating the oven in preparation for a four-course meal. Despite my anxiety, I was looking forward to this short week away from the noise and bustle of London and had planned to take an early-morning stroll the following day to savor the wildflowers and sylvan air.

What ignorance. Even as Ramsey lifted his glass for a toast, unwelcome guests were moving through the garden.

Basil-beef broth had been served, with its rainbow sheen of delicate oils trembling on the surface and a flavor that turned the tongue into the very sunlit hill where the bulls snorted and swung their heavy heads. The broth was met with appreciation (the kitchen was close enough to the dining room, just a door away, that I could hear every chuckle and whisper of praise). I had just arranged the duck. The brick oven had surpassed my expectations; the cherry glaze flowed like molten bronze over the fowl and pooled in crucibles of grilled pear. The servants were carrying the platter to the table when a frightful noise at the front vestibule brought all levity to a halt.

I opened the kitchen door just far enough to poke my head into the dining area. The other staff crowded around me to see. We made a comical sight, no doubt, so many heads peering through one door like the finale of a puppet show.

From there we could see what was left of the entrance. A petard had left a smoking hole where the lock had been. A second later the door was kicked in by a mountain of a man I would come to know as Mr. Apples.

My shock at the sight of this breach cannot be expressed, and so I will content myself with descriptions of a visual nature.

Mr. Apples might have been drawn by a particularly violent child. His torso is massive, but his head is tiny and covered by a woolen hat with earflaps. His shoulders are easily four feet in span. His arms are those of a great ape’s and end in hands large enough to hide a skillet.