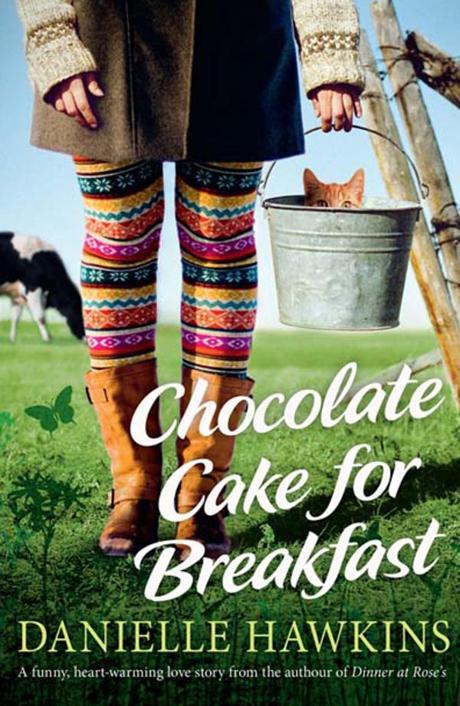

Chocolate Cake for Breakfast

Danielle Hawkins grew up on a sheep and beef farm near Otorohanga in New Zealand, and later studied veterinary science. After graduating as a vet she met a very nice dairy farmer who became her husband. Danielle spends two days a week working as a large-animal vet and the other five as housekeeper, cook and general dogsbody. She has two small children, and when she is very lucky they nap simultaneously and she can write. Danielle’s first novel,

Dinner at Rose’s

, was published in 2012.

Chocolate

Cake for

Breakfast

DANIELLE HAWKINS

First published in 2013

Copyright © Danielle Hawkins 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian

Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Arena Books, an imprint of

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web:

www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 87750 540 9

eISBN 978 1 74343 586 1

Typeset in 13/17 pt Garamond Premier Pro by Bookhouse, Sydney

For Mum, who is awesome

CONTENTS

WHEN THE PHONE RANG ON SATURDAY NIGHT I WAS ON

my knees in the shower, scrubbing grimly at a mould stalactite I had just discovered lurking under the shelf that holds the soap. I would have liked to ignore the phone – having started on the stalactite I wanted to finish the job – but I was on call, so I stood up and reached around the shower curtain.

‘Hello?’

‘What are you up to?’ asked my cousin Sam.

‘Cleaning the shower.’

‘Are you coming to Alistair Johnson’s party?’

I noticed that a medium-sized waterfall was coursing from the point of my elbow onto the clean clothes on the floor, and hurriedly turned off the water. ‘No, I’m on call,’ I said.

‘So what? It’s at the fire station. Miles closer to the clinic than your place.’

‘I can’t be bothered,’ I said feebly.

‘You’re pathetic,’ said Sam. ‘Come on. It’ll be good for you.’

This annoyed me, mostly because I had a feeling he was right.

The street outside the Broadview fire station was lined with cars when I got there, and there was a cluster of youths around the front door.

Sam was watching the rugby on the big screen inside, and I went and leant on the table beside him. ‘Christ,’ he was saying, ‘just

pass

the freaking thing . . . Shit, he’s dropped it cold. Bloody idiot.’

‘Hey, Sammy,’ I said. Sam is my favourite cousin; he sells tractors and self-unloading trailers and other bits of serious farm equipment at Alcot’s Farm Machinery. He has a cheerful round face and sticky-up brown hair and exudes fresh-faced boyish charm, and he could sell ice to Eskimos. ‘Is Alison here?’

‘Was half an hour ago,’ said Sam. ‘But then I saw Hamish Thompson collar her, so she might have topped herself by now.’

‘Why didn’t you save her?’ But he had turned his attention back to the rugby, so I went to look for her myself.

I had only gone about three paces when I spotted Briar Coles dead ahead. Briar was in her last year of high school and wanted desperately to be a vet nurse. She had spent every Wednesday for three months with us at the clinic, until the boss couldn’t take it anymore and asked the school not to send her back. She was very sweet, and very dim, and she followed you around telling you about her ponies and her dog and getting in your way until you wanted to throw something at the poor girl’s head.

Her face lit up in welcome as she saw me, and taking prompt, if cowardly, action in the face of emergency I smiled, waved and ducked out through a side door.

As I hurried around the side of the building into a handy patch of deep shadow (Briar being a persistent sort of girl), I tripped over someone’s legs stretched across the path. I lurched forward, and a big hand grasped me firmly by the jersey and heaved me back upright.

‘Thank you,’ I said breathlessly.

‘Helen?’ Briar called, and I shrank back into the shadows beside the owner of the legs.

‘Avoiding someone?’ he asked.

‘Shh!’ I hissed, and he was obediently quiet. There was a short silence, happily unbroken by approaching footsteps, and I sighed with relief.

‘Not very sociable, are you?’

‘You can hardly talk,’ I pointed out.

‘True,’ he said.

‘Who are

you

hiding from?’

‘Everyone,’ he said morosely.

‘Fair enough. I’ll leave you to it.’

‘Better give it a minute,’ he advised. ‘She might still be lying in wait.’

That was a good point, and I leant back against the brick wall beside him. ‘You don’t have to talk to me,’ I said.

‘Thank you.’

There was another silence, but it felt friendly rather than uncomfortable. There’s nothing like lurking together in the shadows for giving you a sense of comradeship. I looked sideways at the stranger and discovered that he was about twice as big as any normal person. He was at least a foot taller than me, and built like a tank. But he had a nice voice, so with any luck he was a gentle giant rather than the sort who would tear you limb from limb as soon as look at you.

‘So,’ asked the giant, ‘why are you hiding from this girl?’

‘She’s the most boring person on the surface of the planet,’ I said.

‘That’s a big call. There’s some serious competition for that spot.’

‘I may be exaggerating. But she’d definitely make the top fifty. Why did

you

come to a party to skulk around a corner?’

‘I was dragged,’ he said. ‘Kicking and screaming.’ He turned his head to look at me, smiling.

‘Ah,’ I said wisely. ‘That’d be how you got the black eye.’ Even in the near-darkness it was a beauty – tight and shiny and purple. There was also a row of butterfly tapes holding together a split through his right eyebrow, and it occurred to me suddenly that chatting in dark corners to large unsociable strangers with black eyes probably wasn’t all that clever.

‘Nah,’ he said. ‘I collided with a big hairy Tongan knee.’

‘That was careless.’

‘It was, wasn’t it?’

I pushed myself off the wall to stand straight. ‘I’ll leave you in peace. Nice to meet you.’

‘You too,’ he said, and held out a hand. ‘I’m Mark.’

I took it and we shook solemnly. ‘Helen.’

‘What do you do when you’re not hiding from the most boring girl on the planet?’ he asked.

‘I’m a vet,’ I said. ‘What about you?’

‘I play rugby.’

‘Oh!’ That was a nice, legitimate reason for running into a Tongan knee – I had assumed it was the type of injury sustained during a pub fight. ‘Professionally, you mean?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Where?’

‘Auckland,’ he said.

‘For the Blues?’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s really great,’ I said warmly. ‘Good for you.’

He smiled. ‘Thank you.’

I went right around the building and in again through the main doors, back past the cluster of youths. Sam had turned his back on the rugby and was talking instead to my friend Alison. ‘Hi, guys,’ I said.

‘Where did you vanish to?’ Sam asked.

‘Briar Coles spotted me,’ I explained, ‘so I went and hid for a while. Sammy, do you know someone called Mark who’s about eight foot tall and plays rugby for Auckland?’

‘You mean him?’

I followed his gaze across the room to where a big, dark, powerful-looking man with extensive facial bruising was standing flanked by one teenage girl while another took a photo on her cell phone. ‘That’s the one,’ I said.

‘Helen, you moron,’ said Sam. ‘That’s Mark Tipene.’

I looked again, and went hot all over with embarrassment. It was indeed Mark Tipene, and I was indeed a moron. ‘I just asked him what he did for a living.’

‘What did he say?’ Alison asked.

‘He said he played rugby for Auckland.’

‘Well,’ said Sam, ‘he does.’ When not playing for the All Blacks, where even I knew that he had for years been regarded as the world’s best lock. Whatever it was that locks did.

‘What on earth is Mark Tipene doing here?’ I asked. You just don’t expect to find random All Blacks loitering behind the fire stations of small rural Waikato townships.

‘Apparently he’s Hamish Thompson’s cousin,’ said Alison. ‘Poor bastard.’ Hamish was a strapping young dairy farmer, whose advances she had been resisting ever since he moved into the district, and her patience was wearing a little thin.

Across the room Mark farewelled the teenage girls and was instantly accosted by my uncle Simon, who was Broadview’s mayor and took his position very seriously. The poor bloke should have stayed lurking in the shadows.

‘There you are, Helen!’ said a voice from behind my left shoulder.