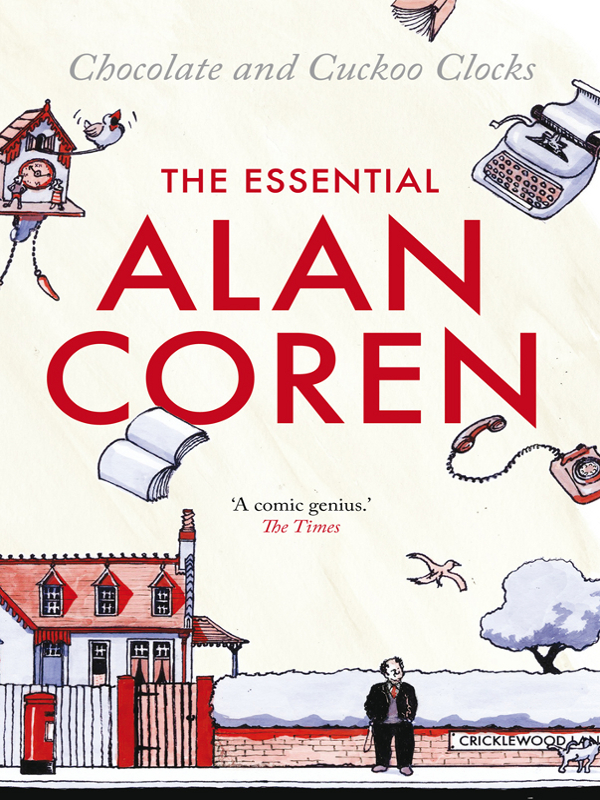

Chocolate and Cuckoo Clocks

Read Chocolate and Cuckoo Clocks Online

Authors: Alan Coren

Tags: #HUM003000, #HUM000000, #LCO010000

CHOCOLATE AND CUCKOO CLOCKS

ALAN COREN (1938â2007) was a celebrated English humorist, writer and satirist who was also well known as a BBC radio and television personality. He was the editor of

Punch

magazine for nine years, and was described by the

Sunday Times

newspaper as âthe funniest man in Britain'.

GILES AND VICTORIA COREN are both writers, living in London.

Chocolate and Cuckoo Clocks

THE ESSENTIAL

ALAN

COREN

Edited by Giles Coren and Victoria Coren

TEXT PUBLISHING MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William St

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

textpublishing.com.au

Copyright © The Estate of Alan Coren, 2008

Foreword and selection copyright © Giles Coren and Victoria Coren, 2008

Introductions copyright © Melvyn Bragg, Victoria Wood, Clive James,

A.A. Gill and Stephen Fry, 2008

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published in Great Britain by Canongate Books Ltd., 2008

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company, 2009

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Coren, Alan, 1938-2007.

Chocolate and cuckoo clocks : the essential Alan Coren /

Alan Coren ; editors Victoria Coren, Giles Coren.

ISBN: 9781921520655 (pbk.)

Ebook ISBN: 9781921834424 (pbk.)

English wit and humour. Great Britain--Social life

and customs--20th century--Humour.

Coren, Giles.

Coren, Victoria, 1972- .

828.91409

âSince both Switzerland's national products, snow and chocolate, melt, the cuckoo clock was invented solely in order to give tourists something solid to remember it by.'

ALAN COREN

Contents

Foreword

by Giles and Victoria Coren

SouthgateâSan FranciscoâFleet Street: 1960â1969

Introduction

by Melvyn Bragg

5. . . . that Fell on the House that Jack Built

6. Under the Influence of Literature

10. Mao, He's Making Eyes At Me!

âThe Funniest Writer In Britain Today': 1970â1979

Introduction

by Victoria Wood

12. Boom, What Makes My House Go Boom?

14. Ear, Believed Genuine Van Gogh, Hardly Used, What Offers?

16. Let Us Now Phone Famous Men

17. The Rime of the Ancient Film-maker

18. Good God, That's Never The Time, Is It?

20. Go Easy, Mr Beethoven, That Was Your Fifth!

21. Take the Wallpaper in the Left Hand and the Hammer in the Right . . .

22. Owing to Circumstances Beyond our Control 1984 has been Unavoidably Detained . . .

23. Foreword to

Golfing for Cats

: An Apology to the Bookseller

24. Baby Talk, Keep Talking Baby Talk

26. And Though They Do Their Best To Bring Me Aggravation . . .

30. The Unacknowledged Legislators of the World

Appendix: The Bulletins of Idi Amin

32. All O' De People, All De Time

Introduction

by Clive James

39. The Gospel According to St Durham

40. O Little Town of Cricklewood

42. For Fear of Finding Something Worse

46. True Snails Read (anag., 8, 6)

The Cricklewood Years: 1990â1999

Introduction

by A.A. Gill

51. Here We Go Round the Prickly Pear

54. Good God, That's Never The Time? (2)

57. Brightly Shone The Rain That Night

59. The Queen, My Lord, is Quite Herself, I Fear

60. The Green Hills of Cricklewood

63. Doom'd For a Certain Term to Walk the Night

66. The Leaving of Cricklewood

67. Lo, Yonder Waves the Fruitful Palm!

Introduction

by Stephen Fry

82. All Quiet On The Charity Front

83. Ah, Yes, I Remember It Well!

by Giles and Victoria Coren

Giles:

So who's going to write the introduction?

Victoria:

I thought we were doing it together.

G:

I don't know. I've never written with anyone else. He never wrote with anyone else.

V:

It's not that hard. One person types, the other one paces . . .

G:

And how do we refer to him? If it's a serious essay, making a case for his inclusion in the canon, he ought to be referred to as âCoren'. But that would be weird, coming from us.

V:

Well, we can't write âOur father'. That sounds like God. âDaddy?' We can't call him Daddy. That's just embarrassing.

G:

Maybe it would be better if someone else wrote it. If we do it, it looks like vanity publishing. Any old twonk can die and have his children bind up his writing and say it's great. Maybe we should ask an academic to do the introduction, to give it some gravitas.

V:

He'd like an academic. For a long time he thought he was going to be one, after all. He spent those two years at Yale and Berkeley on the Commonwealth Fellowship.

G:

And there was post-grad at Oxford before he went. And his First was a serious First. I think maybe even the top one in the year. He got the Violet Vaughan Morgan scholarship.

V:

I always confused that with his medal for ballroom dancing.

G:

No no, that was just called âthe junior bronze'.

V:

Do you think he'd have enjoyed being an academic?

G:

Probably, but I don't think his students would have enjoyed failing their exams because all they had at the end of term was a lot of jokes about Flaubert's haemorrhoids, and an ability to write parodies of Trollope as spoken by two dustmen from Croydon.

V:

He was brilliant, though. It's a rare man who can go on a panel game and work an argument about the exact dates of the Augustan period in English literature into the middle of a John Wayne impression.

G:

He was happier doing it in the middle of a John Wayne impression. Remember how he used the phrase â

homme

sérieux

', with a little flounce of the heel? He thought the very idea of a serious person was somehow preposterous.

V:

He could have made a wonderful tutor in the 1960s, when it was about infusing students with a love of literature, rather than the rigours of critical theory.

G:

But he had a short attention span. That's also why he never wrote a novel. He had ideas for novels, but they were always flashy ideas with a great first sentence. He could never quite be bothered to sit down and write them.

V:

Let's not get an academic to write the introduction. We've got serious people introducing each decade anyway.

G:

Serious like Victoria Wood, do you mean? Or serious like Stephen Fry?

V:

They're serious comedians. And Clive James is a heavyweight.

G:

And A.A. Gill spells his name with initials, which is the

sine qua non

of academia. That's better than being a Regius professor. T.S. Eliot, A.J.P. Taylor, F.R. Leavis, A.C. Bradley . . .

V:

P.T. Barnum.

G:

We still need someone for the 1960s.

V:

The four people doing the later decades have written âappreciations' of someone who was already quite established by then. They're brilliant pieces. But for the 60s, it would be nice to have someone who knew him really well personally, when he was young.

G:

Uncle Gus?

V:

I was thinking more of Melvyn Bragg. They were at Wadham together, they've been friends ever since â and if you asked most British people to name an academic, they'd probably say Melvyn Bragg anyway. Or Peter Ustinov.

G:

Melvyn is a big name. And he does carry intellectual weight. But he won't get the bums on seats at readings in Borehamwood and Elstree like Uncle Gus would.

V:

I'm asking Melvyn. And I think we should do the main introduction ourselves. So what shall we write in it?

G:

Well, if we were going to treat him as a serious writer, we'd start with the Saul Bellow stuff. The lower-middle-class Jewish home in Southgate. Osidge Primary. East Barnet Grammar. The inspirational English teacher, Ann Brooks, who encouraged him to join the library and start reading. Growing up in the war. The mother who was a hairdresser. The father who was a . . . what was Grandpa Sam exactly? A plumber?

V:

That's what they said. I think it's just that he had a spanner. He was an odd job man really. I also heard he was a debt collector.

G:

And I heard Great Grandpa Harry was a circus strongman, but I doubt it was true. Harry was born in Poland in 1885 and left in 1903 before the pogroms started. A smart man is what he was.

V:

Sam and Martha dreamed of Daddy being articled to a solicitor, didn't they? That's the other reason he loved Miss Brooks, because she went round to the house and persuaded them that he should apply to Oxford instead.

G:

God, a solicitor. He'd have been so miserable. And, of course, nepotism being what it is, we'd have ended up solicitors as well. And then we'd have been really miserable too.