Chinese Comfort Women (27 page)

Read Chinese Comfort Women Online

Authors: Peipei Qiu,Su Zhiliang,Chen Lifei

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

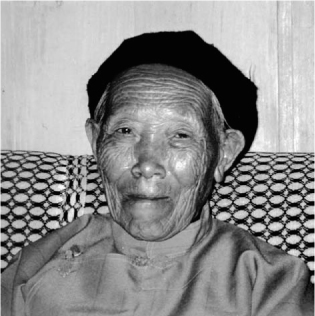

Figure 19

Li Lianchun, in 2001, being interviewed in her daughter’s house.

I was born in the Ninth Lunar Month [1924], but I don’t know the exact date. My birth name was Yuxiu, and my nickname was Yaodi. Yaodi means “wanting a little brother.” I was born in Bai’nitang Village, Lameng Township,

Longling County. When the Japanese attacked this place, I was eighteen years old. I had a younger sister named Guodi. My father smoked opium and didn’t care about the family, so everything fell on my mother’s shoulders. However, my mother became ill and died, so my father’s younger brother took my sister and me to his house. Every day my sister and I went to the mountains to collect hay and sold it in the market, earning some money to help support the family.

On a market day in the summer around the Lunar Eighth Month [of 1942] we went to sell the hay as usual. All of a sudden a group of Japanese soldiers appeared. People at the market tried to hide anywhere they could. I hid in a shop nearby, but the Japanese soldiers found me and jerked me out. They tied my hands and feet with their puttees and stuffed cloth in my mouth to prevent me from crying out … I was then raped by the Japanese soldiers right at the side of the road … [Li Lianchun could not continue talking; she tried hard to control her emotions.] About twenty girls were raped that day. My younger sister barely escaped being raped. She was very small at the time and was not found. I had tried to hide behind the counter in the shop, but the Japanese soldiers found me … [Field investigation indicates that the Japanese troops raped a large number of the local women that day and then moved to Changqing Village before returning to the Songshan stronghold. Soon after, the troops ordered the local collaborators to round up women for the Japanese military comfort stations.]

Around this time my father was drafted for hard labour. A man from the local Association for Maintaining Order said to him: “Send your two daughters to do laundry and to cook for the Imperial Army, then you don’t have to do the hard labour. Your tax can be waived, too.” My father didn’t agree, so he was taken to perform hard labour. The Japanese troops beat him badly. He fell sick upon returning and died soon after. My uncle was unable to support my sister and me. After laying my father to rest, he married me off to a man of the Su family in Shashui Village deep in the mountains. The Su family was very poor and we barely had anything to eat or wear. As I nearly starved to death, I ran away from the mountain village. A team of Japanese soldiers caught me at Bai’nitang when I was almost home and took me to the comfort station at Songshan.

In the comfort station we were given two meals a day while the Japanese had three meals. They ate

baba

[a Yunnan delicacy made of rice powder] but we were given only crude rice. We wore our own clothes at first. Later the Japanese soldiers forced us to wear Japanese clothing. I hated that ugly clothing and didn’t want to wear it. I also hated to do my hair as they asked, but we had no choice.

The Japanese soldiers didn’t call me by my name. They called all of us

hua guniang

[flower girl], but most of the time they spoke Japanese. I didn’t know any of the Japanese words and didn’t want to learn them either. Some of the Japanese soldiers could speak a few Chinese words. When they wanted to call me, they would wave their hands and say,

“Wei, lai, lai”

[“Hey, come, come”]. At mealtimes I heard them say

“Mishi.”

[“Mishi” is not a Chinese word. It might be an incorrectly pronounced Japanese word,

“meshi,”

which means “meal” or “rice.”]

The Japanese army men made us take some sort of medicine, but I didn’t know what it was. During the day when there were not many Japanese soldiers, we had to work, either sewing or making shoes. There were special guards watching us. Many Japanese soldiers came at night. The numbers were different, depending on the day of the week. They liked to pick good-looking girls, so pretty girls had to service more soldiers. The soldiers often beat us. I still have a scar on my left shoulder today. It was caused by a Japanese soldier when he bit me. I also saw the soldiers drag a woman out of her room and beat her. [When asked under what circumstances the Japanese soldier bit her, Li Lianchun seemed to have great difficulty speaking about it. She then showed us her left shoulder. The scar is very long and wide; it is hard to imagine it is a wound from a bite. In order to divert Li from the painful memory, Chen Lifei asked whether the Japanese soldiers paid fees when using the comfort station. Li Lianchun continued.]

Those Japanese soldiers never gave me any money. Money was useless at the time anyway. [Local history indicates that, during the Japanese occupation, Chinese currency was abolished. The Japanese authorities issued “military currency” (

junpiao

), but many Chinese people refused to use it. Therefore, trade in the region at the time was virtually all by the barter system.] The Japanese soldiers didn’t give us anything, and we had to work to support ourselves. During the day we sewed clothes and made shoes to earn food and other things for daily use.

I was kept in that comfort station for about a year. I escaped in 1943, if I remember the time correctly. I looked for opportunities to escape from the day I was taken into the comfort station. As time passed, the Japanese soldiers dropped their guard a little bit. During the day they let me go to the town to collect sewing work. Of course, I was never allowed to go out freely, and there was always a guard watching me. But I gradually made acquaintances among the local people. One of them was an old cowherd who was a distant relative. He agreed to help me escape.

One night, I changed into the old cowherd’s clothes in a latrine before dawn and sneaked out of the comfort station in Dayakou. I left Dayakou, hiding

myself from the eyes of the Japanese troops on the way. I didn’t know where to go. I only knew that I must escape from the west side of the Nu-jiang River and go to the east side.

13

Fearing being caught again, I avoided the main roads and travelled through the mountains. I didn’t have any money, so I begged for food and did labour along the way. Several months later I came to a little town. I had no means to go any further, so I stayed there and married a local man. However, life there became unbearable …

[Li Lianchun fell silent. Later, local people told the interviewers what happened to Li Lianchun in that small town. In November 2001, Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei travelled from Shanghai to Li Lianchun’s home in Yunnan with the documentary film production team of the Shanghai Television Station. During this trip they went to Li Lianchun’s birthplace Bai’nitang to gather more information about her experience before and after the military comfort station and also to verify the sites of her abduction and enslavement. At Bai’nitang they met Feng Puguo, whose cousin’s wife is Li Lianchun’s sister. According to Feng Puguo, the old cowherd who helped Li Lianchun escape was a native of Daqishu Village. He had come to know Li Lianchun through her aunt, who had married a man in the cowherd’s village. After the cowherd helped Li Lianchun get out of the Songshan Comfort Station, she ran to Xiangshu Village in Lujiang-ba, where she crossed the river by raft. Li was later taken by a local warlord, whose surname was Cha, to be his concubine in a place near Pupiao Town. During the struggle to wipe out the local bandits and despots the warlord was killed and Li Lianchun was mistreated. She then ran into the mountains and lived under a cliff at Longdong for about half a year, until she was taken in by Gao Xixian, her late husband. Feng remembered that Li Lianchun had come back once to visit her relatives in 1999.

On the way to Li Lianchun’s home, Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei also made a trip to Changqing Village, which was the first of the places to which Li Lianchun had been abducted. During the war Changqing Village had been occupied by Japanese soldiers who were stationed in the ancestral temple of the Li clan. The village had over two hundred households, of which two-thirds had the family name “Li.” The villagers referred to the temple as the “Lis’ General Temple.” The temple is on a hill and is a well-built, one-story wooden structure. The villagers hold their annual Lunar New Year ceremony in the temple. During the Japanese occupation, the Japanese army’s 113th Regiment had three battalions stationed at Songshan and two companies at Changqing; their headquarters were located in the resident’s house right next to the Lis’ ancestral temple. It was not clear whether the temple had been used as a comfort station or whether this was the Changqing Comfort Station. According to Li Qinsong, an eighty-one-year-old man the interviewers met

in the village, during the war the temple was occupied by Japanese troops and there were Chinese girls confined inside. He said that, during the chaos of the Japanese occupation, most of the women in the village hid themselves deep in the mountains. The Japanese soldiers looted pigs and chickens, but they didn’t stay there for very long. Judging from what he said, the Japanese troops seemed to have launched a “mop-up operation” in the Bai’nitang area, during which they raped Li Lianchun and other Chinese girls. On their way back, the Japanese soldiers stayed at Changqing temporarily and then returned to their Songshan fortress.]

[As Li Lianchun stopped talking, her daughter Gao Yulan, who accompanied Li to the interview, told what happened to Li after she fled into the mountains.]

My mother ran away from that village and fled deep into the mountains in Bingsai, where my father found her and took her to his house. My father was about ten years older than my mother. He was a village doctor and his first wife had died. He was in the mountains gathering medicinal herbs when he saw her hiding under a huge rock. [Li Lianchun’s daughter later took the interviewers to that huge rock. It sticks out from a slope, less than two metres above the ground. Vines growing on the slope hang over the front of the rock, forming a space that had become Li Lianchun’s shelter.] She was almost dead, eating wild fruits and barely surviving. Too much crying had damaged her eyes, so she was nearly blind. She looked like a beggar, wrapped in ragged clothes with her hair tangled. My father felt very sorry for her. He took her home, gave her food, and then treated her illnesses.

My mother was not the only person to whom my father provided refuge. Before my mother, he had taken in another person from a neighbouring village. That person suffered from dropsy and his entire belly was swollen. He had crawled to my father for help. My father let him stay in his house.

My grandfather and my uncle were both veterinarians. They opposed taking my mother in, but my father insisted. My mother’s health gradually improved. She was a very neat and able person, good at both farming and housework. She worked very hard, keeping the house very clean. As time passed, my father fell in love with her. But my grandfather and uncle were against their relationship. My father then moved out of the house; he had no other choice since he wanted to marry her. My father knew about my mother’s past, but he didn’t mind. He often said, “Your mother has suffered a lot, a lot.” [Gao Yulan choked with tears.]

My grandfather lived in Tuanshan-ba in Xia-longdong. My father moved up the mountain to Shang-longdong. To go from my grandfather’s house to my father’s house he had to climb for about thirty minutes. My father built a

little thatched house on the mountain where they got married. My father treated my mother’s illness, first her eye disease and then her venereal disease. My mother said that she had several miscarriages before she gave birth to me.

My father Gao Xixian was truly great. He saved many people’s lives. When he married my mother in the mountain hut, he took the person who had dropsy with them. He even thought of adopting him as his son because my mother might not be able to bear children. That person later had his own family and moved out. When my father died, he came to his funeral like a filial son. We still remain very close, like relatives. My father never charged fees when villagers sought medical help from him, so people would bring him things to show their appreciation. He was well liked by all.

My father built the best house in the village for my mother. He once went to visit my mother’s hometown. He walked several days to the village, only to find that my mother’s elderly relatives had all died. My mother sobbed bitterly. Later she asked me to teach her how to read so that she could travel to her hometown by herself. She learned quite a few characters. She could read some characters, such as those in her name.

My father died in 1971 during the Cultural Revolution. People in the village kept their distance from us after my father died and gossiped about my mother’s past. When my mother went to work, people would stay away from her, so she was always alone. She worked in the field day and night. Life was very, very difficult then. I will never forget what my mother said: “No matter how hard our life is, you must attend school. Only learning can save you from being trodden upon.”

One day it was raining heavily. My mother came to the school to pick me up. Coming directly from the field, she was barefoot and drenched to the skin. Something punctured her sole and pierced through her foot. Seeing that, I cried, “Mum, I don’t want to attend school anymore.” People in the village also urged my mum to let me help her work instead of going to school. But my mother would not agree. She wanted my siblings and me to continue school no matter how difficult it was. Therefore, all the children in my family received an education. My mother supported us single-handedly.