Chinese Comfort Women (14 page)

Read Chinese Comfort Women Online

Authors: Peipei Qiu,Su Zhiliang,Chen Lifei

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

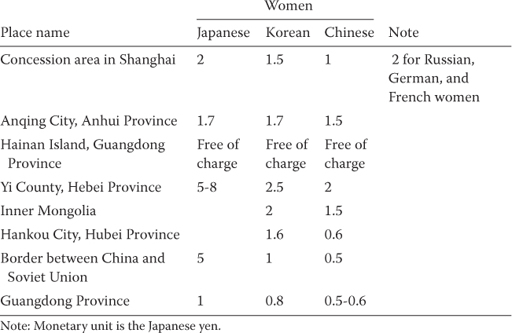

As is clear from the regulations cited above, the formal large comfort stations usually charged fees, which varied according to the user’s military rank. Rates also varied at different stations. In addition, prices were different, depending on whether the service providers were Japanese, Korean, or Chinese comfort women. The following (

Table 2

) is a sample list of fees charged by comfort stations in different places in China. Japanese yen are the monetary units in the chart.

42

The established rates of the South Sector Billet Brothel in Manila (c. 1943 or 1944) reflected similar fee differences based on the nationality of the woman; there, for men of all ranks, the hourly fees for services from Chinese comfort women were set at one-half yen less than were the services from Japanese and Korean comfort women.

43

Rather than reflecting any great difference in the services provided in the comfort stations, the different rate for the women of different nationalities reflected Japan’s imperialistic policy of treating Japanese nationals different from enemy nationals.

The fees charged by the formal comfort stations created a false image, which led to there being some confusion between comfort women and prostitutes. However, the fees that soldiers paid to comfort stations did not function in the same way as did fees paid to prostitutes. This is because the vast majority of comfort women were coerced and then held captive. In addition, most of the money the soldiers paid went to those who ran the comfort stations, while the comfort women themselves received either nothing or only a very small portion of the payments. Regarding how the military comfort station fees were distributed, the “Regulations for the Operations of Comfort Facilities and Inns” (1943) issued by the Malay army administrative inspector provides some detailed information. According to them, comfort women were to receive 40 to 60 percent of the fees based on the cash advances they received.

44

The rules also indicated that three of every one hundred yen the women received were to be put into savings, and over two-thirds of the money comfort women received was to be applied to the repayment of their cash advances. In addition, the rules specified that, if comfort women became

pregnant or fell ill while working, they must pay 50 percent of the medical treatment expenses. For other illnesses, the women had to pay 100 percent of the expenses.

45

Table 2

A sample list of fees charged by “comfort stations” in China

The offering of cash advances was a common method used by procurers when rounding up comfort women from Japan and its colonies. In order to support their families, women from impoverished families accepted a cash advance of up to fifteen hundred yen before being taken into the military comfort stations. Once in the comfort stations, however, it was not easy for these women to pay off their debt because the costs of clothing, cosmetics, and other daily necessities were often added to their debts. What the regulations issued by the Malay army administrative inspector stipulated was the best-case scenario for comfort women from Japan and its colonies, but even in cases in which comfort women became debt-free, much of their share of any payment for services had to be either put into mandatory savings or contributed to national defence.

46

Those who did manage to save any money suffered huge losses when their old yen were converted into new yen and when inflation soared after the war.

47

It has been reported that Korean comfort women who put their savings into military postal savings accounts were unable to withdraw their money after the war. In addition, women who were paid with military currency lost everything because, after the defeat of Japan,

its military currency had no value.

48

Even for the small number of comfort women who reportedly received monetary payment, their experiences still amounted to forced prostitution.

49

According to the account given by Sumita Tomokichi, former engineer of the 6th Regiment, 6th Division, Imperial Japanese Army, published on the website of the conservative organization known as the Association for Advancement of Unbiased View of History (Jiyū shugi shikan kenkyūkai), a Korean comfort woman told Sumita in December 1938 in Hankou, China that her parents had sold her to a Korean dealer for 380 yen and that she had been taken to China to work in the comfort stations run by Koreans: “She said that at the comfort station, each woman had to entertain 25 to 30 men per day, without rest, and very poor food. Many contracted venereal diseases, and there were cases of suicide.”

50

Sumita seems to have posted this account online in order to show that comfort women like this Korean woman were prostitutes who worked for money in civilian-run brothels at the frontlines. Ironically, the content of his account reveals vividly the slave-like condition of the forced prostitution of the comfort women system.

The coercive, exploitative nature of the comfort women system is also clear when one examines the experiences of Chinese comfort women in relation to monetary matters. The vast majority of these women were kept in the stations located on frontlines or in rural areas, where there was no regulation or supervision, and the Japanese soldiers did not have to pay for using these improvised facilities. Of the twelve Chinese survivors whose accounts are presented in this book, none received monetary payment from the Japanese military and several said that, in order to earn the necessities of daily life, they had to take on additional work, such as sewing and cleaning, when not servicing Japanese troops. Even in comfort stations in which tickets were sold, Chinese women received little payment. Wang Bizhen’s 1941 report of the military comfort station at Tongcheng, Hubei Province, for example, has this to say:

The Japanese soldiers who use the comfort station have to go to the ticket office to purchase a paper slip. There are three types of tickets: first class [Japanese women] is 1.4 yuan; second class [Korean and Taiwanese women] is 0.8 yuan; and third class [Chinese women] is 0.4 yuan. Then they go to find the “comfort object” (

weianpin

) according to the number given on the ticket; they are not allowed to choose from the women as they like, nor are they permitted to stay there longer than the given time. A soldier will be charged an additional amount of the ticket fee for every five minutes passed the given time, and he will have one less opportunity to use the facility.

Although the money the soldiers paid to purchase the comfort station tickets is supposed to be given to the women who serve as the “comfort objects,” after many layers of exploitation, very little is left for the women. Moreover, all the medical expenses are charged to the “comfort objects” when they become sick, and the money the women received was not even enough to pay one medical bill. This is how the women suffered under the brutal abuse.

51

The report of the Tongcheng comfort station describes how women drafted from different countries were brutally exploited in a formal military comfort station. The hierarchical nature of the payment practice described in this report is surprisingly similar to that set forth by the South Sector Billet Brothel in Manila and the Malay army administrative inspector in the “Regulations for the Operations of Comfort Facilities and Inns.” It is remarkable that this report, written when the military comfort station system was still in operation, uses the term

weianpin

(comfort object) to characterize all comfort women, regardless of the payment hierarchy created by the comfort station managers, and it clearly distinguishes military comfort stations from commercial brothels.

However, the vast majority of Chinese comfort women confined in improvised comfort facilities did not even receive these paltry service fees. Worse yet, in many cases the families of Chinese comfort women were forced to pay a large amount of money to military comfort stations in their attempts to have the abducted women released. Liu Mianhuan’s story, told in the foreword of this book, is one example. Although Liu was successfully ransomed by her parents, the plan would have failed had she not been too sick to service the Japanese soldiers. The parents of a survivor surnamed Li, for example, paid a large ransom but were still unable to obtain her release until such time as she was physically incapable of continuing to service Japanese troops. Japanese soldiers had kidnapped Li from Lizhuang Village when she was fifteen years old. She was raped and beaten daily by a dozen Japanese troops for about five months. Hoping to ransom Li, her parents struggled and eventually managed to borrow about six hundred silver dollars. However, even after accepting all their money, the Japanese troops still held Li captive. In despair, Li’s mother committed suicide. Li’s father was driven insane by the death of his wife and the capture of his daughter.

52

Testimonies of several other survivors from Yu County and other areas of China recount similar situations.

The extortion, abduction, and abysmal treatment of Chinese comfort women, which was facilitated by the wartime context and the absolute authority of occupation forces, clearly show that the comfort women system was a war crime. Although the sexual violence against women, as has been

properly pointed out, has its roots in the patriarchal social structures and “masculinist sexual culture” not only of Japan but also of the countries victimized,

53

the comfort women system directly resulted from, and explicitly benefited, Japan’s war of aggression. The wartime experiences of Chinese women recounted in the following pages provide further evidence of the criminal nature of the Japanese military comfort women system.

4 Crimes Fostered by the “Comfort Women” System

The institutionalized sexual violence within the military comfort facilities and the random rapes and sexual assaults committed by Japanese troops in the cities and countryside of occupied regions were closely connected to each other and, indeed, were often combined, forming a spectrum of gender-based war crimes. Chinese women bore the brunt of the sexual violence exhibited by the Japanese military both inside and outside the comfort facilities: the establishment of the numerous comfort stations did not prevent but, rather, fostered sexual violence during the war.

According to Tang Huayuan’s investigation, the Japanese 11th Army established military comfort stations at Yueyang County, Hunan Province, in October 1939, but even after that Japanese troops continued raping and assaulting local women in towns and villages. In September 1941, fourteen women who were captured in Jinsha Township (today’s Jingzhou Township) resisted being raped and were brutally killed.

1

On 20 September 1941, five Japanese soldiers gang-raped a young girl in Jinsha Township and then forced her sixty-year-old male neighbour, Wu Kuiqing, to have sexual intercourse with her in front of the troops. Indignant, Wu punched the Japanese soldiers; the soldiers then beat Wu to death with heavy sticks and threw his body head first into a manure pit.

2

A month later, the troops went to Ouyangmiao Temple (today’s Heyan Village Market, Xinxiang Township) where dozens of women and children had been hiding. The soldiers forced two sixty-year-old women to crawl naked in a courtyard, whipped them until their lower bodies were swollen, and thrust bayonets into their vaginas. The soldiers then raped the other women and forced mothers to have sexual intercourse with their sons, and fathers with their daughters, for the soldiers’ entertainment. Those who resisted were executed.

3

Large-scale sexual violence also occurred in Fengyang County, Anhui Province. Before the Japanese army seized the county seat on 1 February 1938, many local residents had fled, but they returned after 2 February when the occupation authorities guaranteed their safety. However, on 5 February Japanese troops suddenly closed the city gates and began killing residents.

Within five days as many as five thousand civilians were killed and hundreds of houses were burned down. A large number of women, from the ages of eleven to seventy, were raped – not even the pregnant women were spared. One pregnant woman was murdered after being raped; then the rapist-murderer cut open her abdomen and plucked out the foetus with his bayonet. After the mass rape the Japanese army retained a number of the victims to serve as comfort women.

4

After this massacre, on the night of 3 May 1938, soldiers from the Chinese New Fourth Army managed to capture two Chinese traitors and free the detained comfort women.

5

However, the Japanese army retaliated on the following day, killing 124 Chinese civilians who were unable to escape from Fengyang. Saying that the city residents had colluded with “mountain bandits” in the 3 May rescue, Japanese troops rampaged through the Siyanjing and Sanyanjing areas on 8 May, killing eighty civilians and machine-gunning another fifty near the city’s west gate. When the soldiers discovered that Chinese civilians had taken refuge in a Roman Catholic church, they set fire to it, killing those inside. The soldiers raped the women caught during the rampage and forced their family members to kneel alongside to watch. If any family member showed the slightest resentment, the raped woman and her entire family were killed. In order to avoid rape and torture, many young women committed suicide by throwing themselves into rivers and wells. In Siyanjing, a well more than thirty metres deep was filled with women’s bodies.

6

These mass rapes and murders all occurred in areas with fully operational comfort facilities. This suggests that, rather than preventing violence, as claimed, the comfort women system officially sanctioned sexual violence and fostered criminal behaviour.