Chinese Cinderella and the Secret Dragon Society (10 page)

Read Chinese Cinderella and the Secret Dragon Society Online

Authors: Adeline Yen Mah

A gasp rippled through the crowd. The grownups looked at each other, many peering around fearfully for Japanese sympathizers. I wondered if Johnny was going to be arrested on the spot for making seditious public statements! Instead, a stout, middle-aged Chinese woman, dressed in a silk qipao, pushed her way through the crowd and approached Johnny’s bench.

‘Come down at once!’ she ordered sternly. ‘Time to go home!’

Afterwards, I begged Grandma Wu to teach me kung fu. I told her I wanted to fight like David.

‘Do you know that the words kung fu ( ) actually mean “mastery of a difficult task” – any difficult task?’ Grandma Wu said. ‘What you’re really asking to learn is

) actually mean “mastery of a difficult task” – any difficult task?’ Grandma Wu said. ‘What you’re really asking to learn is

wu shu

( ), martial arts, which has a long tradition in China, going back over two thousand years. The martial arts we practise here at the academy were brought into China from India fourteen hundred years ago

), martial arts, which has a long tradition in China, going back over two thousand years. The martial arts we practise here at the academy were brought into China from India fourteen hundred years ago

by a monk called Bodhidharma. He settled at the Shaolin Temple in Henan province and developed a series of physical exercises to keep fit between bouts of meditation. These exercises are known as Shaolin temple-boxing.

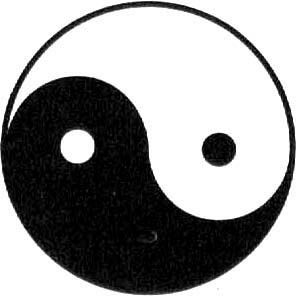

‘Chinese martial arts are also influenced by Taoism and the forces of yin and yang. Yin ( ) represents female energy: that which is negative, dark and cool. Yang (

) represents female energy: that which is negative, dark and cool. Yang ( ), on the other hand, represents male energy: that which is positive, bright and warm. The two forces regulate the universe.

), on the other hand, represents male energy: that which is positive, bright and warm. The two forces regulate the universe.

‘The emblem of our society is the symbol of yin and yang. Let me draw it for you.

Diagram of the Great Ultimate Tai-ji Tu

As you can see, the two fish together form a perfect circle. There is a little yin in every yang and a little yang in every yin.’

‘I just want to be able to defend myself, Grandma Wu,’ I told her.

‘But first you must understand the principles underlying martial arts,’ Grandma Wu said firmly. ‘Let me tell you a story. Eight hundred years ago during the Yuan dynasty, a Taoist priest saw a bird and a snake fighting outside his window. He noticed how both animals alternated soft, yielding movements with hard, quick strikes. From these observations, he developed t’ai chi quan ( ), shadow-boxing. The initial movements of t’ai chi are soft and relaxed to allow you to flow with your opponent’s strength until you find an opening. Then you surprise him by striking with a sudden, hard force. That was how David defeated Johnny.

), shadow-boxing. The initial movements of t’ai chi are soft and relaxed to allow you to flow with your opponent’s strength until you find an opening. Then you surprise him by striking with a sudden, hard force. That was how David defeated Johnny.

‘To be a kung fu expert, you must first be in good physical and mental health. Without basic fitness, you can’t even tumble or break your fall to protect yourself, let alone launch an effective attack.

‘Mentally, you must respect your teacher, pay attention during training, cultivate your patience, do your exercises conscientiously, and persevere until you achieve your goal.’

‘How do I begin?’ I asked, my head spinning.

‘I’ll teach you some basic moves. Promise me that you’ll practise them every day. We’ll work on stretching first, so you can maintain your

balance. One day, your movements will be as fast and powerful as David’s today. Only then can you claim to know kung fu.

‘Watch me now!’ instructed Grandma Wu.

Grandma Wu went over the exercises for each day. She showed me how to stretch, meditate and do t’ai chi. This was to be followed by 150 press-ups, side-bends, sit-ups, squats, dumb-bell circles and 100 jumping jacks using a rope. Finally, she said, ‘The whole regime will take at least two hours. We’ll measure your body weekly and you’ll soon develop into a true martial artist. Eventually, if you persevere, you might even become a kung fu expert. This is something that I do every morning as part of my warm-up exercises.’

She lay face down on the ground and started doing press-ups. At first she used two hands, then one hand, then three fingers of one hand. She ended her demonstration with 100 press-ups in rapid succession with her arms fully extended, using only her thumbs.

As I watched her with mounting respect, I remembered the proverb Johnny had used to describe David earlier. And I knew with certainty that David’s

chu shen ru hua

had been inspired by her.

7

Poster from Marat’s Big Brother

Although I had been living at the academy for only three days, my life had changed radically. So I was shocked when Grandma Wu gave me my tram fare the next morning and told me to go to school as usual. How could I go back to my old life? What if Father sent someone to the school to find me? Now I really felt like Cinderella returning to her rags after being at the ball.

But my fears were unfounded. Father didn’t come to school and my classmates didn’t notice anything different about me. I sat next to my best friend, Wu Chun-mei, as usual, and we played ping-pong at lunch break. In our English class, Teacher Lin told us to write about what we liked doing best and why. I wrote about writing, how I loved it more than anything else. When I wrote,

I could be anyone I wanted to be. I could solve problems or change people’s behaviour any way I wished – the way I couldn’t in real life.

After school, it was strange to get on a different tram from the one I usually took. When I returned to the academy after school, I found Grandma Wu, David and Sam sitting around the kitchen table. Marat was holding a mailing tube.

I threw my bag down and joined them. Marat was trembling.

‘Sit down, CC,’ said Grandma Wu. ‘Something miraculous has happened. You know about Ivanov, Marat’s big brother? When the Japanese arrested him two months ago we thought they might have killed him. Now this tube has arrived, addressed to me, in Ivanov’s handwriting!’

I nodded, remembering what Marat had told me about Ivanov, and how the Japanese had hated him since he solved his friend Simon Kaske’s murder in Harbin.

Marat’s face fell as he opened the tube. There was no letter, only a colourful poster with a picture of a large clock, its hands set to twelve o’clock. The poster proclaimed that all clocks in Japanese-occupied China must henceforth be set to Tokyo time. ‘When it is twelve o’clock in Tokyo,’ the words said, ‘it is twelve o’clock everywhere in China. Those who disobey will be severely

punished.’ The poster was printed by the New Order of East Asia in Shanghai and had been sent on behalf of the Japanese Imperial Army.

We were speechless. Then Sam spoke up: ‘Why would Ivanov send us something like this?’

‘The proclamation is in five languages,’ Marat mused, raking his fingers through his hair. ‘Only the top line is in Chinese. Then there are Japanese, English, French and Russian versions. Ivanov is fluent in all these languages. Maybe he’s translating for die Japanese and was told to send these posters to the public. Perhaps this is his way of telling us that he’s alive.’

‘I have an idea,’ Grandma Wu interrupted. She unrolled the poster and placed it face down on the table. Then she fetched an electric iron and plugged it in.

‘What are you doing?’ Marat asked.

‘I’m waiting for the iron to get hot,’ she answered. ‘I know your brother well. Ivanov is very smart. I may be wrong but I think he is sending us a message.’

Grandma Wu held the iron above the poster without touching it. We all crowded around, feeling the radiating heat.

‘Now!’ Grandma Wu exclaimed. In one sudden, dramatic motion, she lifted the iron and revealed the back of the heated poster. To our astonishment,

we saw line after line of spidery brownish-black Chinese characters.