China Witness (31 page)

Authors: Xinran

Old Mr Wu, his wife and I sat down on little square stools in the outer courtyard. I told them that I felt there had been words between the lines in our interview yesterday, and this was why I had made a special trip for an unofficial interview.

When Old Mr Wu heard this, he suddenly knelt down in front of me and burst into loud weeping.

"The government appropriated the 10.2

mu

of land allocated to me. It was all agreed – I was going to get over 60,000 yuan for it, to be paid in full in ten years. That was the rule. They were going to give me six thousand every year, but it's been seven years now, and they haven't even given me six hundred. They don't give me money and they don't give me land. This is what makes me angry! I've gone to speak to the people in the township government, I've been to the county government, and I've been to see the head of the law court, but nobody would listen to me, only people with no real power, and when they'd heard me out, they just said: 'Plenty of people have this problem, your turn hasn't come yet.' To this day nobody's given me an explanation.

"Where's the money? It's in the hands of the production brigade. They

say they're borrowing it. The production brigade's taken it to dig ditches and roads, and I haven't seen a fen! I'm a peasant, with no money and no land. I'm old, and I can't do much business. How are my old lady and I supposed to live? That's what hurts me most. I'd like to buy a gong and go up to Beijing to shout out my grievances! I've been treated so unfairly!

"I've had such a raw deal, fifty years a Party member, working all these years. Back in Land Reform they only allocated me three

mu

of land! It took another forty years, till Reform and Opening, before they gave me my ten

mu

, and I lived off that land. Seven years and no money! I've been treated so unjustly. I'm wronged! Officials these days aren't like in my day. If they'd done that, Chairman Mao would have had their heads chopped off !"

Sitting opposite Old Mr Wu, the "written complaint" he had paid someone to write on his behalf clutched in my hands, my heart ached. These peasants who thought that young Westerners in fashionable "begging jeans" were poor, and that doing hard, ill-regarded labour in the city was to "enjoy life and make big money", did not even have the basic information or understanding they needed to live in the same era. But they had never made demands for a better life to the rich and powerful who requisitioned them into bankruptcy. Yet those "mother and father officials" who have survived until today only because the peasants kept to their work instead of throwing down their hoes to make revolution and class struggle apparently never paused in their daily banquets to consider the price the peasants have paid with their blood and sweat.

China's peasants have been treated as a part of the 10,000 things of nature, a group that nobody notices. People are concerned about the melting of the ice caps, they fret over the disappearance of the Asian tigers, they fume at the desert swallowing up the green lands, they even have interminable discussions over the right combination of vitamins for every dish of food. But how many people are calling out for an improvement in the living conditions of the Chinese peasants? How many people pause to consider the bowls of weak vegetable soup in China's poverty-stricken villages, with just a few grains of rice added to stave off hunger? How many people would go to read a story like "The Gourd Children" or "The Monkey King" to the children of poor farmers who don't even know which end to open a book at or where to start reading from on the page, so that those hearts, whose first awareness was of days and nights of hunger, cold and disease, can have their share of goals and beautiful memories like the rest

of us? How many people realise that helping those poverty-stricken, uneducated peasants begins with wresting power from local officials who in turn have no education and simply do not understand the law?

China has become strong, China has stood up, but we cannot stand on the shoulders of the peasants for the world to admire how tall we are. We cannot let the peasants' blood and sweat water the tree of our national pride.

Carrying on a Craft Tradition:

the Qin Huai Lantern-Makers

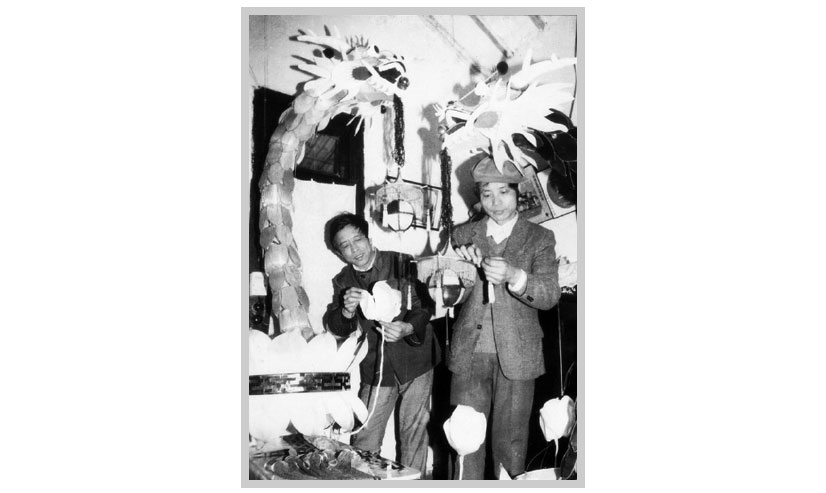

The Huadeng brothers in their workshop, Nanjing, 1950s.

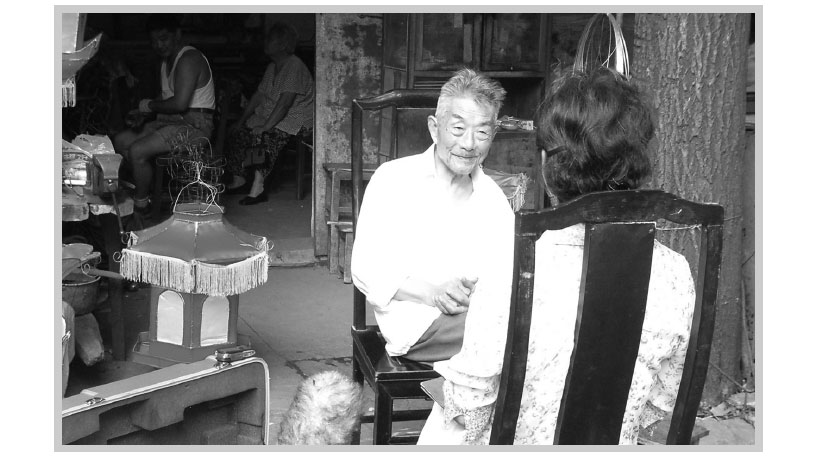

Interviewing lantern-maker Mr Li, at his workshop, 2006.

M

R

H

UADENG

, born in 1934 of a poor lantern-making family and now owner of the Qin Huai lantern workshop, and Li Guisheng, aged ninety, master lantern-maker, and his former apprentice,

Gu Yeliang,

interviewed in Nanjing, capital of Jiangsu

in eastern China by the Yangtze River. It is said that the first

lantern fair was held here in 1372 when

Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang

ordered a spring lantern festival to celebrate both the coming New

Year and the prosperity of the country. This tradition was passed

down from generation to generation for centuries, but declined in

the early twentieth century. In 1985 the lantern festival was revived.

Mr Li is the oldest proponent of lantern-making and he and Mr

Huadeng want to inspire a new generation to carry on this ancient

tradition.

In the Chinese world, there are many who are hostile to the way film director

Zhang Yimou has presented China to overseas audiences in films such as

Raise the Red Lantern

and

Hero

. They feel that Zhang Yimou is feeding a Western appetite for the exotic with uncouth Chinese folk customs which are a relic from the past. He is pandering to the developed world by presenting to them the humiliatingly backward face of China. In other words, he's using our warm Chinese faces to cosy up to foreigners' cold bums!

I do not know if these critics have any notion of the level of understanding of China in the rest of world.

In my ten years of wanderings outside China, I have read the English-language press every day. I have conducted impromptu surveys and asked questions about things which concerned me during visits to scores of countries. It has taught me something which I dared not believe before and am unwilling to believe now: that perceptions of China in the world today are like those of a tiny baby's first impressions – limited to mother's milk. They know this mother's milk exists but, not being capable of enlightened reflection, they cannot envisage its form. As for the sound and the way it grabs their attention, well, they have practice in distinguishing it and reacting to it, but cannot differentiate between the classic and the popular versions.

Among the world's total population of 6.6 billion, China's 1.3 billion is a huge "unknown quantity". Knowledge about China is so small, it is a decimal fraction many positions after the decimal point.

Some misconceptions about China: people in the developed world do not believe that we have had international airports for over half a century and swimming pools for more than a century; people in developing countries mistakenly feel that for us, as for them, military domination is necessary to achieve peace; undeveloped countries are grateful for the fresh milk we give them, but are not convinced that it is as fresh as it could be.

As people all over the world learn to understand China, Zhang Yimou's films have made them aware of Chinese history and displayed to them the brilliant colours of its folk traditions. These films have also given audiences a taste of a 5,000-year-old cultural tradition, albeit on a level with mother's milk.

So many foreigners with whom I have broached the subject have told me that their first impression of China was Zhang's

Raise the Red Lantern

. The majestic Qiao family compound, the refined elegance of its furnishings, the fascinating costumes of the women, the ceremonies and rules which governed the life of the family and the social class to which it belonged – everything in the film is so very different from anything else in the world. What foreigners say they find hardest to understand is the appalling jealous hatred between clan members; easiest to understand is the red lantern which symbolises their passions!

Foreigners are amazed that Chinese people still use folk art in their daily lives, and confess shamefacedly that, to them, preserving folk art and customs means sticking them in a museum so that people can go and look at them. The Chinese, on the other hand, make folk art a part of living, a tradition which is preserved through family life.

I remember, during the discussion after a lecture I had given, an Australian professor, overcome with emotion, standing up and responding to a journalist who had accused modern China of being confused about its identity and culturally reckless. He said: "I teach history in a university. National culture and folk customs will never disappear in a country which has a film director like Zhang Yimou, who can see folk culture as world culture. As people adopt an international language to interpret the world, they will see Chinese folk culture as a part of the spirit of the Chinese people, and it will also play an important part in convincing them that the world needs China, needs to respect and coexist with China."

I completely agree with him. Thank you, Zhang Yimou!

This is also why I chose Qin Huai lanterns, from among countless folk art forms, as one of the chapters for

China Witness

. Amid the ups and downs of Chinese cultural history, these lanterns stand out as a beacon of colour.

As agricultural civilisations evolve into modern civilisations, many traditional ways of life and folk art forms are neglected and disappear. People always wake up to this fact when it is painfully obvious that it should not have happened, but by then it is too late to do anything about it.

In recent years in China, calls to rescue old buildings and preserve old customs have grown louder by the day. "Worn-out old things" which survived the excited rush, in the last century, to tear down the old and replace it with the new and modern, are now respected by scholars and art experts as cultural relics of old China. Folk arts which bear witness to our past have been reclaimed from "silly old fools". Bright colours are no longer seen by the educated as peasant rubbish, and village-style flowered bedspreads have become fashion items for city people. Traditional red mandarin-style jackets are popular wedding gear, and time-honoured snacks and "big-bowl tea" for communal drinking can be seen again on the avenues and in the lanes of every city at dawn and dusk. What are generally called peasant-style lanterns once more hang decoratively in cities where their ancestors were born.

The reappearance and growth in popularity of the Qin Huai lanterns of Nanjing is one of the signs of this trend.

The

Yuan Xiao Lantern Festival originated in the

Southern dynasty (ad 420–589) in ancient Nanjing, capital of the

Jiangsu province, on the south bank of the Yangtze River. From the middle of the Tang dynasty, which succeeded it, the

lantern-makers settled in the area around the Da Bridge at the north end of Pingshi Street, forming the original "Yuan Xiao lantern city". The first Ming emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang, who established his capital in Nanjing, was a huge lantern enthusiast. He gathered together rich merchants to build his new capital, and enhanced its splendour by decorating it with lanterns. At the 1372 Yuan Xiao Festival, 10,000 water lanterns were lit, at his orders, on Nanjing's Qin Huai River. He commanded that the annual lantern festival be extended to ten nights, making it the longest such festival in Chinese history. Mentions of Qin Huai and Nanjing lanterns in plays and novels can give us a glimpse of how spectacular they were then.

Lanterns have always been popular among ordinary people because they are inexpensive, make good gifts when visiting friends and are symbols of good luck. With the political turbulence which followed the end of the Qing dynasty and the establishment of the Republic in 1911, the destitution of Nanjing's population brought a decline in lantern festivals. They almost came to a complete end during the period of the Cultural Revolution, and it was only in 1985 that the annual

Qin Huai Lantern Festival was revived by the city government. Even though history had blown out Qin Huai lanterns several times, they were a traditional custom

which the people of Nanjing refused to give up. Like a torch passed down through the generations, they enable this part of our cultural heritage to survive to the present day.

There is a popular saying in Nanjing: "You haven't had New Year if you don't see the lanterns at the Confucian Temple; and if you don't buy one, then you haven't had a good New Year."

With the aid of my old colleagues at Jiangsu Broadcasting, I tracked down some of those people who gave Nanjing people a good New Year – a group of old

Qin Huai lantern-makers. We spent a few months doing phone interviews and then settled on four people. Two of these were the Huadeng brothers, who had at first worked together to carry on the family tradition of lantern-making, although, after making a name for themselves, they had chosen to go their separate ways. The other two, Master Li and his apprentice Gu, had been introduced and paired up by "government edict", but in the course of their work became friends and today are more like father and son to each other.

The older Mr Huadeng politely but firmly said no to an interview in the end, so we could only visit the lantern workshop of the younger brother.

On 24 August 2006, early in the morning on our way to the lantern workshop, our driver treated us to a tirade about the speed at which Nanjing's roads were being rebuilt. "You can see how hard it's making life for us drivers! You wouldn't believe it, I've been driving in Nanjing for twenty years and I don't know how to get you there! I tell you, I knew the way a week ago, but now I'm not sure! I heard on the radio that a small flyover that was being repaired over there hasn't been reopened yet, and the big flyover next to it is going to be rebuilt, starting this week, so it's shut to traffic. How are drivers supposed to choose a route, tell me that? You gave me an address which any Nanjinger knows, but how am I supposed to know which roads are up for repair, and which are open to traffic? Buy a street map? You must be joking! Street maps can't keep up with road repairs! Go to the city planning office and check their road-works programme for an up-to-date transport map? That's a bit naive. You really don't know anything about China today, do you?! The city planners keep being made to change things by their bosses. Haven't you seen it on the TV and in the papers, the way the planners just hand over the drawings for the politicians, who think they know it all, to draw in what they want? If it's a politician with a bit of brains, then Nanjingers might get some city planning which preserves those features which are

typical of the Jiangnan region; but if they're just some dogsbody, you might end up living in a rubbish bin!"

None of us dared argue with him, because it would have been adding fuel to the flames, and besides, what he was saying had a lot of truth in it. I thought that probably anyone who's driven a car in China would agree with him.

Strictly speaking, the younger Mr Huadeng's Jiangnan Dragon Lantern Factory was not really a factory, more of a workshop. It looked like an abandoned warehouse compound, or a car breaker's yard, with all available space filled with lanterns in the process of being brought to life. From the smallest – the rabbit lantern, about the palm width of a two-year-old child's hands in size – to the biggest dragon lanterns, they filled the compound's two hundred square metres. Half a dozen workers were absorbed in the painstaking task of making lanterns, and nodded to us by way of a greeting. Mr Huadeng led us into a cramped cubbyhole which served as his "office". Seven or eight documents which looked like report forms hung in a row from small clips at the bottom of the window above the desk. On the desk stood a telephone covered with a piece of embroidery, an electric fan noisy enough to stop us talking, and some old-fashioned photo albums with corner mounts that had been put out ready for us. Apart from these, the desk held almost no other office equipment. A display cabinet stuffed full of sample lanterns stood behind Mr Huadeng's office chair, and a dilapidated sofa, obviously intended for guests, faced the window, squeezed in next to the display cabinet. In the whole factory, this was the only place for guests to sit.

The weather that day was forecast to reach a very hot forty-one degrees – the electric fan roared as if it was on fire. Because we needed to record and film, there was no option but to turn it off. Very soon we all began to pour with sweat, and Mr Huadeng looked like he was being interviewed in a shower of rain.

*

XINRAN:

Mr Huadeng, when did you start learning about lanterns?

HUADENG:

I was born in 1934, and all I remember is our home being made up of lanterns. The men of the family, my father and grandfather, when they weren't out selling vegetables, made lanterns; and the women, my grandmother and mother, did the cooking and the laundry, and then made lanterns too. Every corner of the house was full of lanterns. At festivals, they were what we played with, hung up, even what we talked about

when guests came. Before I was ten years old, I probably thought everybody made their living from lanterns. It was only later that I realised the lantern business was seasonal. You couldn't sell them all year round, although they were my family's main source of income. For the rest of the time, we scraped by on the money my father earned from buying vegetables wholesale and selling them in the market. But it was the money from the lanterns which paid for clothes or things for the house or things for the old folks. So every Chinese New Year, the adults in the family would take the lanterns they'd been making all year to the Confucian Temple to sell. When I was ten years old, my father began teaching me how to make them. I started from the most popular kinds, rabbit and water-lily lanterns. Between the age of ten and now, I haven't stopped once.

XINRAN:

And when did your father start making them?

HUADENG:

I don't know. We children weren't allowed to ask grownups questions like that. I only know my father learned from my grandfather. As they used to say, we were a lantern family, we sold lanterns for money. All arts and crafts workers were considered lower than the smallest officials, along with beggars, and other artists, singers, acrobats, martial artists and suchlike. Of course, that's the old way of speaking. When I was ten, to give the family a bit more of an income, my father took me and my older brother in hand and taught us how to make them. He told us how the skills had been passed down through the generations. I still remember him saying, if you sell vegetables, you eat gruel; if you sell lanterns, you eat rice; and if you sell good lanterns, and lots of them, you can eat pork and duck.

XINRAN:

Did he tell you stories about your family and lanterns?

HUADENG:

Mostly what he talked about was how to make good lanterns. What we wanted to know was how to make lots, and make good ones, so we could eat pork and duck. Eating duck was what we dreamed of in those days. It's our most delicious Nanjing speciality! People nowadays would say: "How much can a ten-year-old understand?" But at ten, I was wise for my age. Isn't there a saying: "Poor children soon learn to be head of the family"? As we were learning, my father used to tell us how strict my grandfather had been when he taught him. My father said, if you don't follow the rules, you won't be able to do something well.