China Bayles' Book of Days (60 page)

Read China Bayles' Book of Days Online

Authors: Susan Wittig Albert

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General

Culpeper lived in a time when it was politically dangerous for anyone but licensed physicians to dispense medical knowledge. Trained as an apothecary and motivated by a desire to make medicines available to common people, Culpeper translated into English the Latin

London Pharmacopoeia

, a closely held handbook of medical preparations. He published his work as

The London Dispensatory

(1651), naming and ridiculing the exotic “pharmaceuticals” that the Royal College prescribed: thirteen kinds of dung, the brains of sparrows, the hearts of stags, the horns of unicorns, powdered earthworms, fox lungs, horse testicles. Of one preparation, he says, “’Tis a mess altogether.” It’s no wonder that the enraged College put Culpeper on trial for witchcraft!

Culpeper followed the

Dispensatory

with the first English textbook on midwifery and childcare, emphasizing nutrition and cleanliness and recommending herbal remedies for common problems of pregnancy and childbirth. After that came his most famous work:

The English Physician.

The book listed the medicinal uses of plants found in the garden, hedgerow, and field, and indexed these to common illnesses, using astrological terms that his readers already understood. He recommended “simples,” rather than elaborate compounds, and wrote his recipes in a readable, humorous style. He sold his book for a mere three pence, so that even the poorest could buy a copy—and they did.

The English Physician

has appeared in more than 100 editions in the 350 years since its first publication.

More Reading:

Culpeper’s Medicine: A Practice of Western Holistic Medicine

, by Graeme Tobyn

“The People’s Herbalist: Nicholas Culpeper,” by Susan Wittig Albert,

The Herb Companion

, June/July 2002, pp. 35-39

OCTOBER 19

On those foreign hillsides where wild herbs grow, they reproduce themselves naturally. . . . When the plants’ underground roots or rhizomes branch off and send up new plants, we say the plants have spread by their roots. A little farther along our hillside there is a colony of plants that multiply from their bases; every year each plant has a larger base with more shoots coming from it; we say these herbs multiply from their crowns.

—THOMAS DEBAGGIO, GROWING HERBS FROM SEED,

CUTTING & ROOT

Divide and Multiply

Dividing your herbs to multiply them is good for you (dividing gives you more plants, for free!) and good for the plants (dividing discourages disease by thinning foliage). The best candidates for division are the perennial herbs that die back in the winter and return, larger than life, in the spring. In the southern half of the U.S., dividing these plants now will give them time to settle in for vigorous new growth in the spring. In the north, you may want to mark the plants now (before their tops die back) for division in early spring.

Whenever you do the work, you’ll need a shovel and a sharp knife. Dig around the circumference of the clump, then lift the root mass out of the ground. Shake off the soil or wash it off with a hose. Pull the clump apart, or divide the mass into pieces with the knife, trying to keep a large root system with each division. (Sometimes a clump will yield a dozen or so new plants; the larger the divisions, the less transplant shock the plant will suffer.) Dig a hole for your new plant, put it in, and water thoroughly.

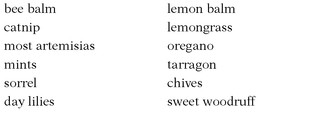

HERBS TO DIVIDE

More Reading:

Growing Herbs from Seed, Cutting & Root

, by Thomas DeBaggio

Is not October the first of the Months of the Spade—the month when one ought to start trenching and double-trenching, planting and transplanting, and doing back-aching things all day?

—WILFRID BLUNT, A GARDENER’S DESIGN

Who can endure a Cabbage Bed in October?

—JANE AUSTEN, SANDITON

OCTOBER 20

Witch-hazel blossoms in the faal,

To cure the chills and Fayvers all.

—EARNEST THOMPSON SETON, TWO LITTLE SAVAGES

Witch Hazel

When you see a witch hazel (

Hamamelis virginia

) in its spectacular late-autumn dress, you may understand how Native Americans felt when they encountered this native golden beauty. Is it any wonder that native peoples believed that the plant was a gift from the Great Spirit?

POWERFUL MEDICINE

Witch hazel was an important ceremonial herb. The Penobscot and the Potawatami used the twigs in cleansing sweat baths and drank witch hazel tea to encourage sweating. The Menominee used the seeds as sacred beads, and to predict the recovery of an ailing person. The Mohicans used forked witch hazel sticks to locate underground water, and colonists eagerly did the same. But while “witching” for water may sound spooky, the name “witch hazel” has nothing to do with the supernatural. In England, small trees (ash, elm, hazel) were cut, or coppiced, to encourage the growth of pliant shoots, or

wyches

, for bows and woven fencing. Witch hazel shrubs reminded colonists of the coppiced trees back home.

Because it is soothing, cooling, and astringent, witch hazel is used as an ingredient in many skin lotions. Try some for yourself.

CUCUMBER-MINT AFTER-BATH SPRITZER

2 tablespoons fresh mint leaves

½ cup boiling water

2 cucumbers

¼ cup witch hazel

1 teaspoon aloe vera gel

Pour boiling water over mint leaves, cool, strain. In a blender, puree cucumbers and strain juice. Mix ½ cup cucumber juice with mint infusion, witch hazel, and aloe vera gel. Pour into a clean spray bottle and store in refrigerator for up to a week. Shake before using.

More Reading:

New England Natives: A Celebration of People and Trees

, by Sheila Connor

The bark affords an excellent topical application for painful tumors and piles, external inflammations, sore and inflamed eyes. . . . A tea is made from the leaves and employed for many purposes, in bowel complaints, pains in the sides, menstrual effusions, bleeding of the stomach. In this last case, the chewed leaves, decoction of the bark or tea of the leaves, are all employed with great advantage.”

—CONSTANTINE RAFINESQUE, 1830, DESCRIBING CHEROKEE,

CHIPPEWA, AND IROQUOIS USES OF THE HERB

OCTOBER 21

Outwardly applied, it stops the Blood of

Wounds, and helps to unite broken Bones.

—JOHN PECHY, COMPLEAT HERBAL OF PHYSICAL PLANTS, 1694

The Comfrey Controversy

Comfrey, a revered herb-garden perennial, has large leaves and a stout root that is mucilaginous even after it is dried. Its use in the treatment of fractures has given comfrey the long-lasting reputation indicated by its name, which is related to the Latin verb

confervere

, to grow together. Its genus name,

Symphytum

, comes from the Greek, “to cause to grow together.” Other names: knitbone, knitback, boneset.

Both the leaves and the root were a popular remedy in earlier times. The Greeks used the root to treat wounds, believing that it encouraged the torn flesh to grow back together. A comfrey poultice hardens like plaster, and was often used as a cast for broken bones. A tea was brewed of the leaves and drunk for respiratory and intestinal ailments. By the Renaissance, it was being used for everything from bruises to sore throat and whooping cough, and in nineteenth-century America, it was prescribed for diarrhea, dysentery, and menstrual discomfort, as well. It was also eaten as a vegetable in Ireland and northern England, and the leaves were sometimes dried and added to flour.

Scientific studies have affirmed comfrey’s “grow-together” properties. Both the leaves and the root (but especially the root) contain allantoin, a chemical that promotes the growth of new cells. However, some studies have indicated that excessive amounts of the herb, taken internally over an extended period, can cause liver dysfunction. It has been argued that comfrey is so unsafe that it should never be used; however, in a study published in the journal

Science

, the researcher pointed out that a cup of comfrey tea posed about the same cancer risk as a peanut butter sandwich.

Comfrey poses the same questions for us that are posed by all phytomedicines—in fact, by any medicine. What are the benefits of its use? What are the negative side-effects? Is it safe? Am I likely to be sorry? Whether we’re taking something prescribed by a doctor or grown in our gardens, these are good questions to ask.

More Reading:

The Healing Herbs

, by Michael Castleman

Each divers soile,

Hath divers toil.

Some countries use,

what some refuse.

—THOMAS TUSSER, FIVE HUNDRED POINTS OF HUSBANDRY, 1573

OCTOBER 22

It is extolled above all other herbes for the stopping of bloud in . . . bleeding wounds.

—JOHN GERARD, HERBAL, 1597

Golden, Golden, Goldenrod: From Susan’s Journal

Today is one of those days when the Texas prairies outshine my garden, for the goldenrod is in bloom, its golden glory blazing across the fields.

The genus name of this remarkable plant is

Solidago

, which means “to make whole.” It has been used as a healing herb since ancient times and grew throughout Europe, but the goldenrod market perked up when the Old World discovered that the New World had it in great plenty. The plant was baled, loaded onto ships, and taken to England to be sold in the apothecary shops, where two ounces might fetch a gold crown.

For Native Americans, goldenrod was a staple medicine, and since there were some two dozen species growing across the continent, at least one was in reach of nearly every tribe. It was used as a wound healer, but also employed in the treatment of headaches, fevers, diarrhea, coughs, stomach cramps, and kidney ailments, as well as rheumatism and toothache. They chewed the roots, brewed the roots and stems, and made poultices of the leaves. Calling it “sun medicine,” some tribes used it in their steam baths, but it was also made into a charm, smoked with other tobaccos, woven into baskets, burned as an incense, and made into a dye.

Oh, yes, a dye. It

does

make beautiful colors, especially for wool. Using different mordants with different parts of the plant, I have obtained lovely shades of gold, orange-flushed tan, burnished olive, and shimmering gray.

And if that’s not enough to convince you of this value of this golden plant, consider this: Discovering that its sap contained a natural latex, Thomas Edison bred the plant to increase the rubber yield and produced a resilient, long-lasting rubber that Henry Ford had made into a set of tires. Edison was still experimenting with his goldenrod rubber when he died in 1931. His research was turned over to the U.S. government, which apparently found it of little importance, even when rubber became almost impossible to get during World War II.

Goldenrod rubber. Imagine that.

Read more about goldenrod, and other Prairie wildflowers:

Legends & Lore of Texas Wildflowers

, by Elizabeth Silverthorne

And in the evening, everywhere

Along the roadside, up and down,

I see the golden torches flare

Like lighted street-lamps in the town.

—FRANK DEMPSTER SHERMAN, “GOLDEN-ROD”

OCTOBER 23

Today or tomorrow, the Sun enters the sign of Scorpio.

The eighth sign of the zodiac, the masculine sign Scorpio (the Scorpion) is ruled by Pluto, formerly by Mars. Although Scorpio is a fixed water sign, its early association with Mars suggests fire, as well. And while Scorpio people may appear calm and unruffled on the surface, they can be as volatile as an undersea volcano. Intense, tenacious, with great willpower, they may also be secretive, compulsive, and easily hurt.

—RUBY WILCOX, “ASTROLOGICAL SIGNS”

Scorpio Herbs

Until this century, Scorpio was ruled by Mars. Now, astrologers assign Scorpio to Pluto, which was discovered in 1930. Physiologically, Pluto is said to rule the process of catabolism and anabolism, the continuous death and regeneration of body cells, and is particularly related to cleansing and the elimination of toxins. Pluto’s regenerative influence also manifests itself in the sexual union (Mars rules sexual desire). Diseases of Scorpio are said to be involved with the buildup of toxic substances, particularly in the urogenital, intestinal, and reproductive systems. Herbs of Scorpio include: