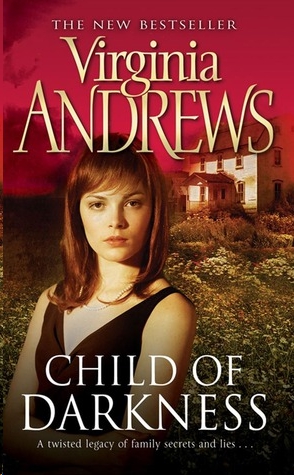

Child of Darkness

Gemini #3

V.C. Andrews

Copyright (c) 2005

ISBN: 0743493850

.

.

Doctor Clayton Feinberg

State Forensic Psychiatrist

Community General Hospital Psychiatric Unit Notes on patient Celeste Atwell, Age seventeen

Background Information

(Provided by investigating officer Steven Gary, Sullivan County Sheriff's Department):

Celeste Atwell lived with her mother, Sarah Atwell, and an infant who is thought to be Celeste's mother's child, fathered by her second husband, Dave Fletcher, deceased. They lived on a farm on Allen Road just a mile or so southeast of the hamlet of Sandburg, New York. The infant is also named Celeste, but was distinguished in the home from the first Celeste by the family referring to her as Baby Celeste.

However, identical names for two siblings never became an issue because for some time immediately after the apparently accidental death of her twin brother, Noble, Celeste Atwell was brought up as her twin brother. She was made to assume a male persona and to deny all of her feminine characteristics. At the time of Noble's death, Sarah Atwell convinced the law enforcement authorities that her daughter, Celeste, was a kidnapped and missing child. The reasons for all this subterfuge remain obscure. There is an ongoing investigation as to the actual cause of Noble Atwell's death, Baby Celeste's lineage, and the events recently transpired that resulted in Betsy Fletcher's death.

Dave Fletcher's daughter, Betsy, moved into the residence recently with a male child born out of wedlock, one Panther Fletcher. Some altercation between Betsy Fletcher and Celeste Atwell resulting in the death of Betsy Fletcher occurred either right before or soon after the death of Sarah Atwell. The best information we have at this time is the death was caused by a fall on the stairway during a struggle that resulted in Betsy Fletcher breaking her neck. Celeste Atwell then buried Betsy's body in the family's herbal garden.

Coroner's inquest concludes Sarah Atwell died of heart failure. It has also been concluded that her remains remained in her bed for at least two to three days.

The county sheriff's department brought the patient to the psychiatric ward following the order of the Honorable Judge Levine, assigning her to my care, and to perform an analysis to determine whether or not she can be held accountable for her actions and whether or not she can be of any assistance toward the solution of these additional questions.

After a night during which she was sedated, she was brought to my office for her initial visit.

.

First Psychiatric Evaluation Session

The patient was remarkably comfortable and at ease despite the traumatic events that had brought her to the psychiatric ward to be placed under my care. She appeared to understand where she had been taken, and offered no resistance nor voiced any complaints. Her complacency led me to feel she had a fatalistic approach to her own affairs and destiny. After establishing the necessary trust between us for my session, I conducted a dialogue, the highlights of which I have so noted below.

.

Patient Interview

I see from the police report that you said you were trying to keep Betsy Fletcher from carrying a pot of boiling water up the stairs. You said she was threatening to throw it on your mother, who was not well and was in bed?

Celeste Atwell Yes.

Why did she want to do that?

Celeste Atwell: She thought my mother was stealing the money her father left her and wouldn't give it to her

And it was during the course of that struggle between you and Betsy to keep her from hurting your mother that she fell down the stairs and broke her neck?

Celeste Atwell: Yes.

If you killed Betsy Fletcher accidentally, Celeste, why didn't you call the police or call for an ambulance? Why did you bury Betsy Fletcher in the herbal garden?

Celeste Atwell: Baby Celeste told me to do that.

Why would you listen to a six-year-old? (The patient smiled at me as if I was ignorant.)

Celeste Atwell: Baby Celeste is not just a sixyear-old. She has inherited the wisdom of our family. Our family spirits told her what to tell me.

How do you know they told her these things?

Celeste Atwell: I know. I can sense when they are with her and she is with them.

Celeste Atwell: Baby Celeste is special, very special.

Aren't you special to them, too? (The patient showed some agitation and did not respond.) Was there another reason, Celeste? Was there some reason that prevented them from speaking to you directly?

Celeste Atwell: Yes.

What was it?

Celeste Atwell: I had disappointed them. They were angry with me.

Who exactly was disappointed in you and angry with you?

Celeste Atwell: All of them. All of the spirits of my family, their souls.

How did you disappoint them?

Celeste Atwell: I. . .

What made them angry at you, Celeste? (Patient became more agitated. I gave her a glass of water and waited.) Can you tell me why you think you disappointed them, now, Celeste? I would really like to know.

Celeste Atwell: I let Noble die again.

How did you do that? Wasn't Noble already dead? How can he die again if he's already dead? (At this point the patient would not respond to any question. She kept her eyes closed and her lips tight. Her body began to tremble. I determined I had gone as far as I could for the first session.)

.

Doctor's Feinberg 's Conclusion

Celeste Atwell suffers severe intense guilt and pain over the death of her twin brother, Noble. We have not established the reason yet, but my best estimate is she will and should remain under psychiatric care and treatment for some time and should be remanded to the psychiatric hospital in Middletown. At the time of her actions and at this time, she was and remains incapable of understanding the consequences of her actions or the difference between an illegal act and a legal act.

-- Doctor Clayton Feinberg

.

From Baby Celeste's Diary

.

A long time ago when I was in pediatric therapy, my doctor asked me to write down

everything I thought, everything I saw, and everything I believed happened and was happening to me. It was something I never stopped doing. It was truly as if I was afraid that all of it was a dream, and the only way to prove it wasn't was to write it down so I could read it later and tell myself, See, it did happen. All of it did happen!

.

I

wouldn't go until I had brushed my hair. Mama al-ways spent so much time on my hair while Noble sat watching, as if he were jealous and wanted to be the one to brush it. Sometimes I let him, but he would never do it in front of Mama because of how angry it would make her. He would make these long, deliberate strokes, following the brush with his hand because he needed to feel my hair as much as see it. As I looked at myself in the minor, I could almost feel his hand guiding the brush. It was hypnotizing then, and it was hypnotizing to remember it now.

"Mother Higgins said right now," Colleen Dorset whined and stamped her foot to snap me out of my reverie. She was eight years old and my roommate for nearly a year. Her mother had given birth to her in an alley and left her in a cardboard box to die, but a passerby heard her wailing and called the police. She lived for two years with a couple who had given her a name, but they divorced, and neither wanted to keep her.

Her eyes were too wide, and her nose too long. She was doomed to end up like me, I thought with my characteristic clairvoyant confidence, and in a flash I saw her whole life pour out before me, splashing on the floor in a pool of endless loneliness. She wasn't strong enough to survive. She was like a baby bird too weak to develop the ability to fly.

"Where that baby bird falls out of the nest," Mama told me, "is where she'll live and die."

Some nest this was, I thought.

"Celeste, you'd better hurry."

"It's all right, Colleen. If they don't wait, they don't matter," I said with such indifference, she nearly burst into tears. How she wished there was someone asking after her. She was like someone starving watching someone in a restaurant wasting food.

I took a deep breath and left the small, almost claustrophobic room I shared with her. There was barely enough space for the two beds and the dresser with the mirror above it. The walls were bare, and we had only one small window that looked out at another wall of the building. It didn't matter. The view I had was a view I owned in my memory, a view among others I gazed back at the way people peruse family albums.

The walk to the headmistress's office suddenly seemed longer than ever. With every step I took, the inadequately lit hallway stretched out another ten. It was as if I was moving through a long, dark tunnel, working my way back up to the light. Just like Sisyphus in the Greek myth we had just read in school, I was doomed never to reach the end of my long and difficult climb. Each time I approached the end, I fell back and had to begin again, as though I were someone caught in an eternal replay, someone tormented by wicked Fate.

Despite the act I put on for Colleen, as soon as I was told I was to meet with a married couple who might want to become my foster parents and perhaps adopt me, my heart started to thump with anticipation. The invitation to an interview came as a total surprise; it had been years since anyone had any interest in me, and I had just celebrated my seventeenth birthday. Most married couples coming to the orphanage look for much younger children, especially ones just born. Who would want to take in a teenager these days, especially me? I wondered. As one of my counselors, Dr. Sackett, once told me, "Celeste, you have to realize you come with a great deal more baggage than the average orphan child."

The baggage wasn't boxes of dresses and shoes either. He was referring to my past, the stigma I carried because of my unusual family and our history. Few potential foster parents look at you as your own person. It's not difficult to see the questions in their eyes. What bad habits did this one inherit? How has she been twisted and shaped by her past, and how are we going to handle it? Why should we take on any surprises?

None of this was truer for anyone than it was for me. I had been labeled "odd," "strange," "unusual," "difficult," and even "weird." I knew what rejection was like. I had been nearly adopted once before and returned like so much damaged goods. I could almost hear the Prescotts, the elderly couple who had taken me into their lives, return to the children's protection agency and, as if speaking to someone in a department store return and exchange department, complain, "She doesn't work for us. Please give us a refund."

Today, perhaps because of this new possibility, that entire experience rushed over the walls of my memory, where it had been kept dammed up for so long. It pushed much of my past over with it as well, so that while I walked from my room to the office to meet with this new couple, the most dramatic events of my life began to replay. It was as if I had lived and died once before.

Truthfully, I have always felt like someone who had been born twice, but not in any religious sense. It wasn't that I had some new awakening after which I could see the world in a different light, see truth and all the miracles and wonders that others who were not reborn did not see. No, first I was born and lived in a place where miracles and wonders were taken for granted, where spirits moved along the breezes like smoke, and where whispers and soft laughter came out of the darkness daily. None of it surprised me, and none of it frightened me. I believed it was all there to protect me, to keep me wrapped comfortably in a spiritual cocoon my mother had spun on her magic loom.

We lived in upstate New York on a farm that had be-longed to my family for decades and legally still be-longs to me. I was a true anomaly because I was and remained an orphan with an inheritance, property held in trust and managed by my mother's attorney, Mr. Deward Lee Nokleby-Cook. I knew little more about it, but more than one headmistress or counselor had shaken her finger at me and reminded me I had far more than the other orphans.

The reminder wasn't made to make me feel better about myself. Oh no. It was meant to encourage me to behave and obey every rule and every

command, and was usually held over my head like some sort of branding iron. After all, property, having anything of value, meant more responsibility, and more responsi bility meant you had to be more mature. If they had it their way, I would have completely skipped my childhood--not that a childhood in an orphanage was any-thing to rave about, anyway. I wish I could forget it all forever, every moment, every hour, every day, and not have it all come up inside me like so much sour milk.

Despite the fact that I was a little more than six when I left the farm, I still remembered it quite vividly. Perhaps that is because my time there was so dramatic, so intense. For most of my infancy, I was kept under lock and key, hidden away from the public. Even though my mother thought my birth was a miraculous wonder, or perhaps because of that, my birth was guarded as the deepest, most treasured family secret. I was made to feel like someone very special. Consequently, the house itself for nearly my first five years was my only world. I knew every crack and cranny, where I could make the floor creak, where I could crawl and hide, and where there were scratches and nicks in the- baseboard, each mark evidence of the mysterious inhabitants who had come before me and still hovered about behind curtains or even under my bed.

For most of my life at the farm, I was taken out after dark and saw the world outside in the daytime only through a window. I could sit for hours and hours and stare at the birds, the clouds, the trees and leaves swaying in the wind. I was mesmerized by all of it, the way other children my age were hypnotized by television.

I had only one real companion, my brother, Noble. My cousin Panther was just a baby then, and I often helped care for him, but I was also jealous of any attention he stole from my mother and brother, attention that would have been directed at me. Right from the beginning, I resented it when he and his mother, Betsy, came to live with us.

Betsy had lived with us before. She had moved in soon after her father married Mother. I was never quite sure if he was my real father as well, but immediately he wanted me to call him Daddy. He died before Betsy returned. She had run off with a boyfriend, and she didn't even know he had died. The whole time she was away, she had never called or even written a letter to tell her father where she was, but when she returned and learned of his death, she was very angry. I remember she blamed us for her father's death, but she was even angrier about the way her inheritance was to be distributed. The air in the house felt filled with static. Mother stopped smiling. There were ominous whispers in every shadow, and those shadows grew deeper, darker, and wider every passing day, until I thought we would be living in darkness and no one would be able to see me, even Noble.

Before Panther's mother, Betsy, had invaded our home and spoiled our lives, I had Noble completely to myself. He was the one who took me out, the one with whom I worked in the herbal garden and took walks about our farm when I was finally permitted to be out in the daytime. Often he read with me in the living room and carried me to my bedroom to put me asleep. He taught me the names of flowers and insects and birds. We were practically

inseparable. I felt he loved me even more than my mother did. I was so sure that someday I was to understand why; someday, I would understand it all.

And then one day he disappeared. I can't think of it any other way or of him as anything but who he had been to me. It was truly as if some wicked witch had waved her wand over him and in an instant turned him into the young girl I had been told was my half sister, Celeste, after whom I had been named. I had seen pictures of her many times in our family albums and heard stories about her, describing how bright she was, how pretty. It would be years before I would under-stand it, and even then I would wonder if everyone else was mistaken and not me. However, I would learn that my mother believed it was Celeste who had died in a tragic fishing accident, and not Noble, her twin brother.

Eventually and painfully, however, I would discover that it really was Noble who had drowned. Mother re-fused to accept it. She forced Celeste to become her twin brother, and all I knew about Celeste now was that she was in a mental clinic not far from the farm. As I said, I would make many shocking discoveries about myself and my past, but it would take time. It would be a long, twisted journey that would eventually bring me back to my home, to the place where all this began and Where it was meant to come to a finalization, when I would truly be reborn.

I have been told that when I was brought to the first orphanage, I was a strange, brooding child whose de-meanor and piercing way of looking at people drove away any and all prospective adoptive or foster parents despite my remarkable beauty. Even though I was ad-vised to smile and look innocent and sweet, I always wore a face that belonged on a girl much older. My eyes would get too dark and my lips too taut. I stood stiffly and looked as if I would just hate to be hugged and kissed.

Although I was polite when I answered questions, my own questions made the husbands and wives considering me for adoption feel very uncomfortable. I had the tone of an accuser. More than once I was told I behaved as if I knew their deepest secrets, fears, and weaknesses. My questions were like needles, but I couldn't help wondering why would they want me. Why didn't they have children of their own? Why did they want a child now, and why a little girl? Who wanted me more, the man or the woman? They might joke or laugh at my direct questions, but I wouldn't crack a smile.

This sort of behavior on my part, alongside my un-usual past, would sink the possibility of any of them taking me into their home. Even before the interview ended, my prospective new parents would look at each other with NO written in their eyes and make a hasty retreat, fleeing me and the orphanage.

"See what you've done," I was often told. "You've driven them away."

It was always my fault. A child my age shouldn't ask such questions, shouldn't know such things. Why couldn't I just keep my mouth shut and be the pretty little doll people hoped I was? After all, I had auburn hair that gleamed in the sunlight, bright blue-green eyes, and a perfect complexion. The prospective parents were always drawn to me and then, unfortunately, repulsed by me.

At the first orphanage, where I remained until I was nearly ten years old, I quickly developed a reputation for clairvoyance. I always knew when one of the other girls would get a tummy ache or a cold, or when one would be adopted and leave. I could look at prospective parents and tell if they were really going to adopt someone or if they hadn't yet decided to take on such a serious commitment. There were many who were just window shoppers, making us all feel like animals in a pet shop. We were told to sit perfectly straight and say, "Yes, ma'am," and, "Yes, sir."

"Don't speak unless spoken to"

wasn't only written over doorways; it was written on our brows, but I wasn't intimidated. There were too many voices inside me, voices that would not be still.

My first orphanage caregiver was a strict fiftyyear-old woman who demanded we all call her Madam Annjill. As a joke, I think, her parents had named her Annjill, just so they could laugh and say, "She's no angel. She's Annjill." I didn't need to be told. She was never an angel to me, nor could she ever become one.

Madam Annjill didn't believe in hitting any of us, but she did like to shake us very hard, so hard all of us felt as if our eyes were rolling in our heads and our little bones were snapping. One girl, a tall, thin girl named Tillie Mae with brown habitually panicstricken eyes the size of quarters, really had so much pain in her shoulder for so long afterward that Madam Annjill's husband, Homer Masterson, finally had to take her to the doctor, who diagnosed her with a dislocated shoulder. Tillie Mae was far too frightened to tell him how she had come to have such an ailment. She was in pain for quite a number of days. The sight and sound of her crying herself to sleep put the jitters into every other orphan girl at the home, every other girl but me, of course.

I was never as afraid of Madam Annjill as the others were. I knew she wouldn't ever shake me as hard. When she did shake me, I was able to hold my eyes on her the whole time without crying, and that made her more uncomfortable than the shaking made me. She would let go of me as if her hands were burning. She once told her husband that I had an unnaturally high body temperature. She was so positive about it that he had to take my temperature and show her I was as normal as anyone.

"Well, I still think she can make herself hotter at will," she muttered.

Perhaps I could. Perhaps there were some hot embers burning inside me, something I could flame up whenever I wanted to and, like a dragon, breathe fire at her.

I must say she worked hard at finding me a home, but it wasn't because she felt sorry for me. She simply wanted me out of her orphanage almost as soon as I had arrived. Sometimes I overheard her describing me to prospective foster parents, and I was amazed at the compliments she would give me. According to her I was the brightest, nicest, most responsible child there. She always managed to slip in the fact that I had an inheritance, acres of land, and a house kept in trust.

"Most of my little unfortunates come to you with nothing more than their hopes and dreams, but Celeste has something of real value. Why, it's as if her college education or her wedding dowry was built into any adoption," she told them, but it was never enough to overcome all the negative things they saw and learned.

"Where are her relatives?" they would inevitably ask.

"There aren't that many, and those that there are were never close. Besides, none of them want the responsibility of caring for her," was Madam Annjill's reluctant standard explanation. She knew what damaging questions her answers created immediately in the minds of the people who were considering me. Why didn't her relatives want her? If a child had something of value, surely some relative would want her. Who would want a child whose own relatives didn't want to see hide nor hair of her, land in trust or no land in trust?