Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs (22 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

Today, it barely matters how many children invite Adam to their birthday parties, because he is filled with the confidence that only self-understanding, genuine acceptance, and loyal friendship can bring. Now, if asked, Adam will tell you that, although he doesn’t like having TS, he does not wish to be “typical,” because the insight gained since his diagnosis has made him a better person who gives others grace and cares deeply about his community. And, he adds, “Now I have all the friends I need.”

Rachel Ezekiel-Fishbein and Joel I. Fishbein

Pennsylvania couple

Rachel Ezekiel-Fishbein

and

Joel I. Fishbein

often bicker when writing together, but easily agree when communicating about their son, Adam, who was diagnosed with Tourette syndrome and ADHD in 2005. Ezekiel-Fishbein is a freelance writer and publicist; Fishbein is an attorney, known as “defender of all that is right.” Ezekiel-Fishbein has been a driving force for improving special education and family advocacy in her community. Contact them at [email protected].

T

o win without risk is to triumph without glory.

Pierre Corneille

I was thirteen when my Binghamton, New York, Boy Scout troop planned a camping trip. I wasn’t afraid of being out in the woods at night, but the thought of being with a group of people terrified me. I stammered severely, and kids sometimes made fun of me.

However, I summoned up the courage to go on this outing for I knew that there would be at least one person I could spend time with: my best friend. A friend who had never been put off by my disability, whose father owned a meat market a block away from where my father operated an Army/Navy store. A friend with a “fantastic” imagination. Sitting apart from the other campers, in the dark of the woods, alert to the spooky night sounds, my friend would tell stories of life on other planets, of beings he imagined would be found there, of time traveling to other worlds, of ghosts, of the meaning of dreams, of reincarnation, of the ability to read minds. I sat spellbound as he elaborated a string of “what if” stories. He wanted to be a writer, and I was certain he would be.

My friend’s name was Rod Serling. He became the fantastic writer he dreamed of being and more. As creator of the television show

The Twilight Zone,

his influence on science fiction has been “astronomical.”

I was so certain that Rod would attain his dream that I was almost too embarrassed to tell him mine. I wanted to be a defense attorney like Clarence Darrow and Sam Leibowitz. I’d read everything I could about them, including transcripts from their trials. I’d spent hundreds of hours alone at the library, imagining myself a golden-tongued attorney pleading sensational cases before juries.

But I knew I could never be like Clarence Darrow and Sam Leibowitz because of my speech impediment. “You’ll make it,” Rod would say, never once discouraging me. “Don’t worry. The stammering will go away, and you’ll be a great lawyer one day.” When I felt discouraged, Rod would cheer me up with a tale about an attorney defending a three-eyed creature from another planet. I’d laugh and feel better, his confidence in me encouraging my own confidence in myself.

Eventually, I did attain my dream of becoming a lawyer. Still, it was preposterous to think a stammerer like myself could perform in a courtroom. I conceded as much and planned to return home, to help my father run his Army/Navy store, and then perhaps to branch into legal research where I could silently earn a living.

Thoroughly depressed, I sank into my chair at the 1951 University of Miami Law School commencement. When I looked up, I couldn’t believe my eyes: There at the podium stood the keynote speaker, Sam Leibowitz! Leibowitz was the famous New York attorney who had saved the lives of nine Alabama black men falsely accused of raping two white women in the famous “Scottsboro Boys” case. That afternoon Leibowitz, his voice filled with conviction, told us that defense attorneys were the key to keeping America free, that the protective ideals of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights were constantly under attack, that “authorities” were chipping away our rights to a fair trial, to the presumption of innocence, against unreasonable search and seizure, and to proof beyond a reasonable doubt. He warned us that the old guardians were dying out and that without a new generation to take up the fight, America would succumb to a reemergence of robber barons and torture chamber confessions, and that the average man and woman would be stripped of dignity and liberty, and would then be legally and economically enslaved.

Leibowitz challenged us to take the torch he was passing, to become defense attorneys, and to protect America. I felt as if he were speaking directly to me.

Because of Leibowitz’s speech, I remained in Miami to become a defense attorney, stammering or not. Soon I got my first case: A black man named Henry Larkin, who had shot and killed a man in the hallway of his apartment building, was charged with murder. Larkin said the man he shot had come after him with a knife.

Since there were no public defenders in those days, groups of young attorneys would mill around the courthouse volunteering for cases and hoping to be appointed. I was doing just that when someone told me about Henry Larkin. He nearly cried when I offered to represent him.

The day before the trial (my first!), I read in the

Miami Herald

that Leibowitz, then a New York judge, was back in town for another speech. I searched him out, and soon I stood at his hotel door, briefcase in hand. Stammering an apology for my intrusion, I asked for his help.

“I was in the audience at your ca-ca-commencement address here; I became a defense attorney because of you. Now I’m facing m-m-my first case tomorrow.”

Leibowitz smiled and invited me in. I told him about the case. He raised his eyebrows every time I tripped over a word, but never said a thing about my speech impediment and then proceeded to outline my entire defense.

The next day I stood before twelve people in a court of law, with the life of Henry Larkin in my hands, or more precisely, in my misfiring mouth. Then something strange came over me: not fear, but confidence.

My own troubles vanished, replaced by the far greater problems of Henry Larkin. He was a good man who had never broken the law in his life. It was up to me to convince a jury that he had acted in self-defense. I talked for four hours that day, remembering everything Sam Leibowitz told me as I pled for Henry Larkin’s life. The jury took three minutes to decide he was “not guilty.”

One thing missing from the next day’s newspaper report is that I had not stammered once during my entire argument. I tried to call Sam Leibowitz, but he had left town. Needing to share my multifaceted victory with someone, I called Rod and told him about the miracle of my untangled tongue. He exuded elation, and then grew serious. “Ellis, it’s a sign! You’ve found your place in time. You were destined to speak for the innocent and oppressed. Never forget that!” Rod was quick to see some unexplained, universal phenomenon in practically everything. In his eyes, what happened was the result of what can only happen in

The Twilight Zone.

For whatever reason, Rod’s words have stayed with me throughout my life. I’ve been in thousands of trials and have always tried to do my best to defend the “poor and defenseless.” Some people, including my wife, feel I’ve overdone it. I have spent a great deal of time on “pro bono” cases.

I’ve also had my share of wealthy clients, including celebrities, rich businessmen, doctors, and a billionaire Arab oil sheik. Payments come in many forms, such as a handshake, a hug, a baby’s smile, a holiday card, a home-cooked meal, a friendly face in court, even a picketer carrying a sign outside of jail. Henry Larkin, my first client, came by every Friday for the rest of his life and handed me an envelope with a five-dollar bill in it. He never missed a week.

Ellis Rubin As told to Dary Matera

Dary Matera

is the author of fourteen books, including

Get Me Ellis Rubin!, John Dillinger, Most Wanted, Quitting the Mob, What’s in It for Me?, Taming the Beast, Childlight, The Stolen Masterpiece Tracker,

and the

New York Times

bestseller

Are You Lonesome Tonight?

Mr. Ellis Rubin passed away in December 2006. He was eighty-one. Dary lives in Chandler, Arizona. E-mail him at [email protected].

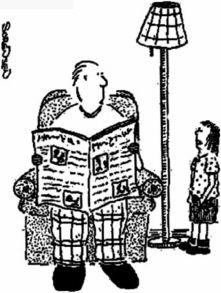

“My imaginary friend says ‘get real.’”

Reprinted by permission of Jean Sorensen and Cartoon Resources. ©2005 Cartoon Resources.

A

winner is someone who recognizes his God-given talents, works his tail off to develop them into skills, and uses these skills to accomplish his goals.

Larry Bird

“Welcome to the parents, family, and friends of our 1998 graduating class . . . As your name is called, please step forward to receive your diploma.”

Looking at the somber faces glowing among the sea of blue and gray caps and gowns, I am overcome with nostalgia. It seems like only yesterday that they were my active and inquisitive first-graders. As the almost-adult girls totter forth one by one in newly purchased heels, and the boys shuffle by in their self-conscious gaits, the public-address system announces their names while I find myself immersed in memories.

Another name is called, and suddenly I am consumed by a vivid flashback of a little, freckle-faced strawberry-blond named Adam. He was a smiley, quiet kid, a conscientious student with beautiful penmanship and detailed, creative artwork.

His mother and I bantered often. She always joked and laughed a lot. She wasn’t laughing the night she called to say that Adam might not be in school for several days.

“Why not?” I asked.

“Well, he’d probably have trouble zipping his pants. He cut his fingers off,” she replied.

Appalled, my immediate response was, “That’s not

funny!”

“No, but it’s true,” she said.

Adam had been at his grandfather’s farm. The family had butchered a cow and was making hamburger. Adam, trying to be helpful, stuck his hand into the meat grinder, severing his fingers and part of his thumb.

I could tell you about the challenges this presented— wearing sweatpants to avoid zippers, anchoring his paper as he learned to cut and once again become the neatest printer in the room, the curiosity and questions his peers asked. But, instead, I want you to meet the little boy who was not willing to accept help. It was the end-of-the-year picnic. I had set up an obstacle course with seven stations to test their athletic abilities and coordination (boys against the girls). All activities except the overhead horizontal ladder were done. The score was tied three to three. Ten girls tried, and eight made it across the “alligator-infested pond.” Eight boys tried, and all eight made it. I declared the score tied, everyone a winner.

Adam said softly, “You didn’t give me a turn.” How could I explain to him that he couldn’t do it? He had no fingers on his one hand to grasp the rungs. “It’s my turn!” he repeated a little louder and climbed the ladder. I stood below to catch him when he fell, ready to hug him and tell him I was proud of him for trying.

I watched with barely contained tears as Adam hooked his left wrist over the first rung. His feet came off the steps, and for a second he was suspended in space. Then with a jerk, his good hand grabbed the next rung. He hooked his wrist over that one and began to advance, one rung at a time.

At first, the class stood frozen silent, almost like a picture. Then one boy chanted, “Go, Adam, go!” He was soon joined by the whole class, all competition forgotten, as their classmate and friend grasped and advanced, grasped and advanced. His little body swung from side to side. “Go, Adam, go!” Clapping, chanting, “Go, Adam, go!”