Chicken Soup for the Kid’s Soul (22 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Kid’s Soul Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

I was six years old when it all started—I was diagnosed with A.D.D./L.D. That means I have attention deficit disorder and a learning disability. That’s a big problem to grasp for someone so young. People were not sure how I would function, and I did terribly. I didn’t want to sit down in class. I remember that the teachers were always on my case. During lessons, I had trouble understanding what the teachers were saying. I worked on my homework from dinnertime to almost bedtime with my parents. It was very hard for me to do homework because I didn’t understand it. I would get frustrated, and then my parents would get upset.

At school, I was in the principal’s office more than I was in the classroom. The teacher would ask me

why

I didn’t understand something, and I would just shout, “It’s none of your business!” at her because I was embarrassed that I couldn’t understand the work. Then the teacher would send me to the principal’s office. I finally started to improve a little, but I still had problems throughout elementary school.

By the time I got to middle school, my behavior was really bad. My worst memories were the rides home on the bus. I remember getting off the bus one day, saying good-bye to the driver, and as the bus left, two guys beat me up. I tried to defend myself, and at the same time, I was trying to flag the bus down. I remember feeling all alone. I walked home with a black eye and a swollen face.

I also remember running my mouth one day to a kid who was bigger than I was. I was defending my brother. I talked trash about the kid’s family. He punched me and accused me of calling him a bad name. I got in-school suspension (ISS) for two days.

The kids where I lived were very mean and hateful, and they called me names like “fatty” and “loser.” This hurt me because I felt inside that I

was

a fatty and a loser.

I felt I was a failure—but I was raised to believe that you are only a failure if you truly believe you are. I didn’t want to be a failure.

When I finally reached seventh grade, I was making D’s and F’s, and pulling ISS all the time. I was always getting the whole class in an uproar by flinging rubber bands and throwing spit wads at the board. I remember punching a boy for calling me a “fat boy.” I got ISS for three days. During those three days, I got the ISS students in an uproar by making fun of what the teacher did and imitating him. For my actions, I got more and more ISS.

My parents started to look for other schools that might help me to learn to function better. That’s when they found Knollwood, a school for special students. I was enrolled last year. It’s great! I know now that there will always be people who care, whether they’re parents or teachers. They will always help, but you have to want to get better to be successful, or it won’t matter how much they do to help you. I finally realized that I could change. I can prove that John Troxler can be a success.

I am no longer getting D’s and F’s. I am making A’s, B’s and C’s. I am now completing the eighth grade, and I am in a tenth-grade social studies book. In other subjects, I am also above average. Though I still have some trouble, I feel deep down inside that my return to a regular school is just around the corner. With the help of my teachers, I will be ready for high school. It has taken me seven years to finally realize that A.D.D. and L.D. are handicaps that I will always have, but I can, and will be, successful and in control. It’s up to me!

John D. Troxler, age 14

I expect to pass through life but once. If therefore, there can be any kindness I can show, or any good thing I can do to a fellow being, let me do it now, and do not defer or neglect it, as I shall not pass this way again.

William Penn

One day, when I was five, I went to a local park with my mom. While I was playing in the sandbox, I noticed a boy about my age in a wheelchair. I went over to him and asked if he could play. Since I was only five, I couldn’t understand why he couldn’t just get in the sandbox and play with me. He told me he couldn’t. I talked to him for a while longer, then I took my large bucket, scooped up as much sand as I could and dumped it into his lap. Then I grabbed some toys and put them in his lap, too.

My mom rushed over and said, “Lucas, why did you do that?”

I looked at her and replied, “He couldn’t play in the sandbox with me, so I brought the sand to him. Now we can play in the sand together.”

Lucas Parker, age 11

Applaud us when we run,

Console us when we fall,

Cheer us when we recover. . . .

Edmund Burke

“Why do you wear such big pants?” kids on the bus would tease. At the after-school YMCA program, kids were equally cruel. I was so hurt by their comments, I didn’t know how to answer back. At the age of nine, I weighed 115 pounds, more than most other kids at school!

I thought of myself as a regular kid. But according to many of the children in my school, I was a nobody. I had friends here and there, but that year, friends began to fade away. My interests were in reading a good book, writing and schoolwork in general. I pulled some of the highest grades in my fourth-grade class. But I didn’t fit in and wasn’t socially accepted because I wasn’t interested in athletics like most of the other boys, and I was overweight.

My one friend, Conner, would stand up for me sometimes with things like, “How can you judge someone you don’t even know?” Conner had a lot of challenges when it came to the other kids making fun of him, too. He had a stuttering problem that became the target of the same kinds of put-downs.

The teasing got so bad that every day after school, I came home either crying or totally destroyed mentally. I was very much a perfectionist in my schoolwork and other interests, achieving goals that I set for myself. I couldn’t stand that I was losing friends and just couldn’t take the joking any longer.

I decided to starve myself. I figured that if I could control my eating habits, I could change my physical appearance and end the teasing. I started checking the calories on the labels of everything I ate. If I could get away with it, I skipped meals altogether. A salad was usually the most I ate in a day. My mom and dad were totally unaware of my plan as long as my lunch box was empty and my cereal was partially eaten.

At dinner, I made excuses about having had a big lunch so I’d only have to eat a few bites, or nothing at all. Whenever possible, I came up with ways to get rid of my food. I’d wipe most of the food into the trash or hide it in extra paper towels. Often, I tried to get my parents to allow me to do my homework while eating so that I could ditch the food without their knowing about it. I was caught up in a contest with myself, and I was determined to win.

Then the sickness and headaches began. I suffered week after week of horrible headaches and endless colds. My clothes no longer fit, and it wasn’t long before I was too thin to wear the new clothes Mom replaced them with.

At that point, my parents realized that I had an eating disorder and rushed me to the doctor. I weighed in at only eighty-three and a half pounds. The doctor told me how dangerous this disorder is to a person’s health. I realized that I was slowly starving my body of the nutrients that it needs in order to function normally. If I kept up this behavior, I could become seriously sick and maybe even die.

The doctor and my parents helped me to set up new, healthy goals for myself. I went to see a counselor, started a weight-lifting program and decided to try playing sports.

My mom heard about a winter-session lacrosse clinic that would help me learn about the sport before I would be expected to compete in it. Lacrosse is big in our area, but I had never given it a try. After the first few clinics, I didn’t want to go back. I hadn’t mastered the game in the first few tries, so the perfectionist in me couldn’t stand not being able to be in control. But I kept going, and finally, I started feeling better and better after each time out on the field. I was getting the hang of the game, and I liked it. Lacrosse gave me then, and still gives me now, confidence in myself. It’s also great exercise, so it helps me stay healthy.

The year after the clinic, I was playing so well that I was chosen to be on a travel team of kids more experienced than I. I began to make new friends with kids on my team, and they don’t tease me. They respect me for working so hard at the game that I can play at their level.

It’s been three years since the beginning of fourth grade, when my life had started to fall apart. What a year! I have learned to find self-esteem in the things that make me special and not in what others say or don’t say about me. I am still the same perfectionist that I was born to be, but I know when I need to stop pushing myself so hard. I concentrate on perfection where it really matters. I still get high grades and love to read and write, and I have also discovered interests like playing the drums, football and tennis. I plan to play basketball during the next season.

Trying to totally change my physical appearance didn’t lead to happiness. I learned that “beauty is only skin deep,” and it’s what’s inside that counts. Getting involved with things that I enjoy has helped my self-confidence, and I have made the kind of friends who like me for who I am—not for what I look like.

Robert Diehl, age 12

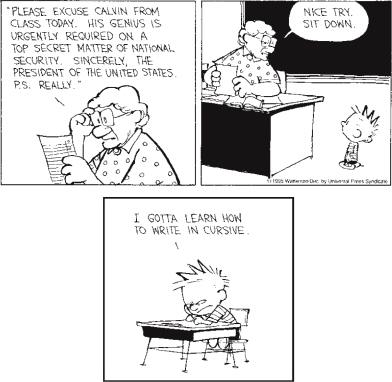

CALVIN AND HOBBES. Distributed by Universal Press Syndicate. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

A

man, as a general rule, owes very little to what he is born with—a man is what he makes of himself.

Alexander Graham Bell

Dear God,

This is Charles. I turned twelve the other day. If you noticed, I’m typing this letter. Sometimes it’s hard for me to write, you know. It’s this thing called dysgraphia. I also have Attention Deficit Disorder—oftentimes learning disabilities accompany A.D.D. My IQ was tested at 140, but if you graded my cursive, you’d think I was dumb.

I never could hold a pencil the right way. I never could color in the lines. Every time I would try, my hand would cramp up and the letters would come out sloppy, the lines too dark, and the marker would get all over my hands. Nobody wanted to switch papers with me to grade them because they couldn’t read them. Keith could, but he moved away.

My brain doesn’t sense what my hand is doing. I can feel the pencil, but the message doesn’t get through right. I have to grip the pencil tighter so my brain knows that I have it in my hand.

It’s much easier for me to explain things by talking than it is to write. I’m really good at dictating, but my teachers don’t always let me. If I am asked to write an essay on my trip to Washington and Philadelphia, it’s like a punishment. But if I can dictate it, or just get up and talk about it, I can tell everyone about the awesomeness of seeing

the

Declaration of Independence in the National Archives or the feeling of true patriotism that rushed through me when I stood in the room where our founding fathers debated the issues of freedom.

If I got graded on art, I’d fail for sure. There are so many things that I can picture in my mind, but my hands just don’t draw it the way I see it.

It’s okay. I’m not complaining. I’m really doing fine. You see, you gave me a wonderful mind and a great sense of humor. I’m great at figuring things out, and I love to debate. We have some great Bible discussions in class, and that’s where I really shine.

I want to be a lawyer when I grow up, a trial lawyer in fact. I know I’d be good at that. I would be responsible for researching the crime, examining the evidence and truthfully presenting the case.

You have told me that you made me special when you said that I am fearfully and wonderfully made. You have assured me that you will see me through, and that you have plans for me to give me a future and hope.

My parents want to help me, so they bought me a laptop to take to school. My teacher is the best this year! I am allowed to do a lot of my work on the computer. We have a character trait book due every Friday, and guess what? She lets me use Print Shop Deluxe for the artwork. For the first time, I’ll be able to show everyone some of the things I have in my mind.

Lord, this is a thank-you letter, just to let you know I’m doing fine. Life’s hard sometimes, but you know what? I accept the challenge. I have the faith to see myself through anything. Thanks for making me

me.

Thanks for loving me

unconditionally.

Thanks for everything.

In your service,

Charles

Charles Inglehart, age 12