Chiara – Revenge and Triumph (3 page)

Read Chiara – Revenge and Triumph Online

Authors: Gian Bordin

She climbed onto the sill and eased herself out of the window, reaching for the foothold she knew was three feet below. She blocked out all thoughts of falling, focusing entirely on the mental image of the wall features she had burned into her mind over several days. Holding on to the outside of the sill with her left hand, she wedged the fingers of her right into a crack in the wall and searched with her right foot for the small opening farther down. Her foot slipped off twice before she felt secure enough to lower herself to the new position and shift her hand holds. It felt like eternity before the bushes brushed her legs some twelve feet down and she dared to jump to the soft earth, immediately licked and smothered by the two dogs.

"Quiet," she whispered. Obediently, they desisted, sitting down, eyes on her. She looked up to her room, wishing that it would again be hers, the sanctuary of her girlhood, a girlhood she was leaving behind, that would be lost forever.

Avoiding the pebble path, she skirted along the bushes to the far side of the garden, followed silently by the dogs. "Quiet," she whispered again, hugging each animal briefly, and then pointed to the house, saying "Go." She was sure their sad eyes revealed that they knew she was leaving. "Go," she repeated, pointing once more to the house, and they wandered slowly away.

Before dipping into the narrow tunnel that led to the secret exit, she cast one last glance at the castle that had been her home. She tightened her jaws to suppress her tears and strengthen her resolve. Then she opened the heavy iron gate that she had oiled a few days earlier so that it would not creak. She locked it again from the other side. At the bottom of the dark tunnel she hid the key behind a loose stone at knee level.

Once below the high garden wall, she hurried down the path to Nisporto. A few hundred feet from the first houses, she left the track and skirted the village. When she was above the fishing harbor, she scrambled down the rocky slope to the shore, where a row of boats of various sizes was drawn up unto the sand. Staying just above the water’s edge, she approached cautiously.

As she reached the first boat, the bark of a dog made her freeze. The clamor of dogs would be her undoing. She knew that the fishermen had been nervous lately about sightings of pirates between the island and Corsica. They had been raided a few years earlier, and she had heard of another village on the southern shore, where all able-bodied men, women, and children had been carried away into slavery. But the single warning was not followed by renewed barking. Hidden in the shade of the boat, she let her heartbeat slow itself. She had intended to look for a rowboat in good shape and small enough for her to handle. However, with the threat of a dog raising the alarm, she dared not venture farther along the beach. If she was to get away, she had no choice but to take this first one.

She carefully inspected its outside hull — rather difficult in the deceiving light of the moon. It had no visible holes but was in bad need of a coat of paint. Peering over the edge, she was relieved to see the oar inside. Her mind was made up. She placed her canvas bag on the little bench at the stern, folded her cape and put it there too. The next task was to get the vessel into the water. First, she tried to push it, but it simply dug itself deeper into the sand. Maybe she needed to pull the boat, lifting its front at the same time. Jerking it forward by a hand width at a time, pausing in between and listening for any sounds, she managed to get the boat afloat. It almost tipped when she climbed in. She used the oar as a pole to push it into deeper water. There were no sounds except the peaceful lapping of the water on its side.

Holding the oar, she was suddenly uncertain of what to do. It had always looked so easy when a fisherman propelled a boat forward in a flowing figure-eight motion. She inserted it in its lock at the stern and tried to imitate the movement. The boat only began to rock from side to side, forcing her to stop and steady it again. With eyes closed, she imagined the fisherman’s motion in her mind and then executed the vision she had seen. Opening her eyes she notices that the boat was moving forward slowly. Repeating this a few times, she got the boat going. The problem was that it tended to curve, and she was forced to lift the oar out of the water to correct the direction. It took her more than an hour before she could propel and steer the boat at the same time. By then the village had disappeared behind a small headland and she was already feeling the strain in her arms.

After resting for a while, she resumed her toil, steering a straight course along the coast in its northeasterly direction, while trying to stay a safe distance away from the rocky cliffs where the waves splashed high and subsided in white foam. She had to rest ever more frequently as her arm and shoulder muscles tired. Dawn was breaking when she could see Capo della Vita to her right and was able to guess the outlines of the coast of Tuscany, two and a half leagues away, more than twice the distance she had already covered. Had she not expected that by daylight she would be well away from the island? And there she was already exhausted, her arms and shoulders leaden that she could hardly move them anymore.

How naive she had been to think she could row across the straits. She would never make it. Maybe she should row back to shore and walk home. She was sure her father would forgive her, and if he saw how desperate she was to avoid becoming Niccolo’s wife, to what measures she was willing to go, he might relent. Wasn’t she the jewel of his heart? It was almost a relief to abandon her quest. Only a nagging fear remained that he might refuse.

As she turned the boat toward shore, she noticed that the point of the cape seemed farther away than before. Was it only an illusion, a trick of the mind that made distances seem larger when one knew that every move sent knives into arms and shoulders? No, she was definitely drifting away from the island. Frightened, she began to row with as much strength as she could still muster, but to her dismay it only slowed her drift away from land. She called out frantically for help until she was hoarse and finally sank into the bottom of the boat, sobbing, holding her knees to her chest, rocking back and forth.

Exhaustion must have conquered her in the end. The sun was straight overhead when she woke, thirsty and hungry. A brisk wind was blowing from the southeast and the boat was rocking from side to side. With each wave, spits of water spilled over the side. She turned the boat perpendicular to the waves and it stopped rocking. The coast of Tuscany dipped in and out of the horizon with every wave. To the south she could see the length of Elba, from Volterraio in the east to the top of Monte Capanne in the west. Whenever she crested a wave, the dark coast of Corsica loomed in the distance. Elba looked at least as far away as she remembered seeing it from Piombino, the only time she had visited the coast of Tuscany. To the northwest, she could make out Isola di Capraia. She was alone, no other boat in sight.

She had the urge to relieve herself, but how? Unless she did it into the bottom of the boat, she would have to climb onto the little bench at the stern. Then she realized in consternation that this also implied removing her breeches. She could not simply raise her skirts a bit and crouch.

Thirst and hunger finally got the better of her, and she drank and ate half her supplies, while occasionally steering the boat back in the direction of the waves in the hope that within a day or two she would either be saved by a passing vessel or reach some distant shore. In vain she continued to scan the horizon in all directions for rescue to arrive.

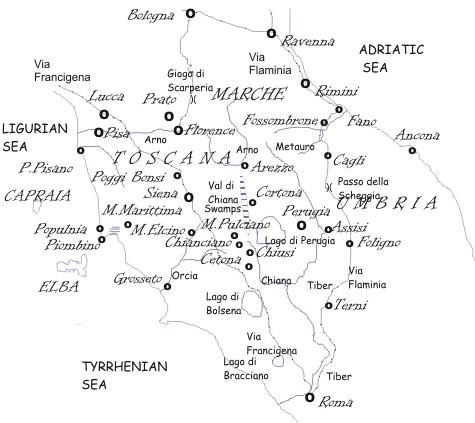

Map of Tuscany

3

Ligurian Sea, early June 1347

I was driven along by the wind and the waves for a day and a night without seeing a living soul. At dawn of the second day I saw the pointed peak of Isola di Capraia a league or two behind to my left. If I had not dozed off sometimes in the middle of the night, I probably could have rowed the boat toward it as I got closer, but by the time I woke the current was too strong for my feeble strength and inexperience. I finished the last of my drink and food, watching the island almost imperceptibly shrink in size.

I wondered why I did not see any other boats. Whenever I had been on top of Volterraio, I had always seen dozens of small fishing boats and even the occasional galley and two- or three-masted lateen vessel. Maybe they were all sheltering from the stiff winds.

How was a feeling? Frightened? Yes. Frantic? No. I had resigned myself. Either God would save me or the sea would be my grave as it had been my brother’s. Once or twice I started to pray, but gave up quickly. Neither God nor the Madonna had responded to my daily prayers when I beseeched them to spare me from Niccolo. And why should they heed the pleas of an obstinate girl. There must be thousands of girls facing the same fate who were appealing to them, and what about all the other women praying for their sick children to get well or for their husbands to return from the sea or from war, not to speak of all the men who prayed to them as well. I felt suddenly small and insignificant. So, I waited and waited. I even stopped scanning the seas for another boat.

By the time I saw the merchantman, a carrack, it was less than a quarter of a league behind and approaching fast, its three lateen sails straining in the wind. I jumped up, shouting with joy, quickly wrapped my cloak around the oar and waved frantically. Maybe God had sent help even without my prayers, and I said a few silent words of thanks.

Two men were standing on its prow and several more along its starboard side. When I saw the ship change course toward me, I lowered the oar, but remained upright, my heart beating fast. I was so glad to see them and know that rescue was at hand that I did not even worry about what to tell them, nor did it cross my mind that they might be pirates. I could hardly wait to be hauled onto its deck.

As the ship got closer, I managed to read its name: Santa Caterina. Something looked familiar about the flag flying on its aftercastle, but I could not put my fingers upon it. Only when one of the two men on its prow turned his face toward the sun and I saw the black patch over his left eye did it strike me. Signor Sanguanero! No, God would not be so cruel as to deliver me into his hands, not after I had gone through all the agony of leaving my father and suffering the hardship of the sea.

Maybe he would not recognize me in my boy’s disguise. But even that hope was quickly shattered. Hardly had they lowered a rope ladder that I heard Niccolo’s outburst of laughter.

"Now look what pretty fish we have caught," he shouted with obvious glee. "Welcome on board, her ladyship, or is it master Chiaro?" He continued grinning from ear to ear.

Abruptly, I sat again, letting go of the rope. I was not going on board of that ship; I would rather drift along for many more days than this.

"Come up, girl, or do you need a special invitation?" He turned to the dark-skinned sailor next to him and said: "Moro, bring her up!"

I could hear his renewed laughter, as he disappeared behind the side of the deck. The sailor slid down the rope ladder like an ape. One look at him and I knew that he meant business. Before I could even react, he had snatched my knife from its sheath. He grabbed my belongings and pushed me so roughly toward the ladder that I almost fell overboard. Once on deck I faced father and son Sanguanero, both smirking. The sailor handed my bag and knife to the father.

"So you are running away," he said as he fingered the knife. "Nice," he added, giving it to his son, and then he emptied the contents of my bag onto the deck. "Or were you by chance so eager to get into your betrothed’s bed that you came looking for us?"

I did not answer, but my face must have betrayed my fear. Niccolo picked up the book and the wooden box.

"I see, the lady can read." He opened the book. "Or do you only look at the pictures?" He frowned and exclaimed: "Look father, isn’t this the one you had wanted to get your hands on?"

The older Sanguanero took it. "Indeed. What a fortuitous coincidence." He began leafing through it.

When Niccolo opened the box and pulled out a diamond necklace, his eyes lit up. "Esteemed Signorina, how thoughtful of you to bring me so valuable a present."

My fear suddenly turned into anger. I was not going to give him the satisfaction of reacting to his sarcasm.

"What shall we do with her, father?"

"We will decide later. She looks parched. Give her a drink and then lock her into our cabin."

He was right. I was terribly thirsty and glad that I did not have to beg for water. Nor did I mind being locked in the cabin as long as I was away from them. The humiliation of it all was almost more than I could bear.

Moro called to one of the sailor to bring water. How strange life is, so full of surprises! Although I did not know it then, I was going to meet your father. The man who brought me a cup filled to the brim was in his mid-twenties, tall, a rugged face, with a mane of golden locks that shone brightly in the afternoon sun. Our hands touched as I took the cup. It felt like something undefinable passed from him to me. I said "thank you" and met his gaze. I had never seen eyes like this before, blue as the sky, deep as the sea. They expressed both curiosity and something else. Was it pity or sympathy? I wrestled mine away and emptied the cup in one go. When I returned it, I thanked him again, losing myself once more in those deep pools.