Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (68 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

10.38Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The human rights community was not at all split. They immediately voiced their displeasure. Michael Posner, the executive director of the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, lamented Annan’s choice. “It suggests that the human rights job is a part-time job that can be done from Baghdad,” he said. “That’s not the signal we want to be sending.”

50

Like almost everyone who knew Vieira de Mello, human rights advocates were sure that he would stay well beyond four months. The human rights groups jointly approached Annan with a list of possible replacement high commissioners. Vieira de Mello was stung. He felt they had never fully trusted him and were using his Iraq assignment as an excuse to nudge him out.

50

Like almost everyone who knew Vieira de Mello, human rights advocates were sure that he would stay well beyond four months. The human rights groups jointly approached Annan with a list of possible replacement high commissioners. Vieira de Mello was stung. He felt they had never fully trusted him and were using his Iraq assignment as an excuse to nudge him out.

After Annan publicly announced his appointment on May 27,Vieira de Mello received dozens of e-mails from friends and colleagues around the world. He would later write to a colleague that “I was never entirely convinced if it was congratulations or commiserations I should have been offered.”

51

Perhaps none of the e-mails was as stark as that from Mari Alkatiri, the prime minister of East Timor, who recalls writing a two-line note that read: “Sergio, be careful. Iraq is not East Timor.” Secretary of State Powell telephoned and told him that the resolution’s vagueness offered him an opportunity to give the UN a strong role in Iraq. When Vieira de Mello said that he had every intention of seizing upon the ambiguity, Powell laughed and said, “Well, if you go too far, we’ll let you know.”

52

51

Perhaps none of the e-mails was as stark as that from Mari Alkatiri, the prime minister of East Timor, who recalls writing a two-line note that read: “Sergio, be careful. Iraq is not East Timor.” Secretary of State Powell telephoned and told him that the resolution’s vagueness offered him an opportunity to give the UN a strong role in Iraq. When Vieira de Mello said that he had every intention of seizing upon the ambiguity, Powell laughed and said, “Well, if you go too far, we’ll let you know.”

52

On May 29, the UN’s new Iraq envoy sent out a group e-mail to thirteen close friends who had written to him. He thanked them in five languages for their notes and wrote that he was going to Iraq “with mixed feelings.” On the one hand he wanted to do what was “best for the UN.” But on the other he was “conscious of the many pitfalls, of my own ignorance and of the Security Council’s mandate ambiguities” and “sad that my personal life again comes last, yet energized and inspired by Carolina.”

53

53

Even if he was conflicted about going to Iraq himself, he was pleased that the UN had been summoned.The deployment of the UN mission was proof of America’s dependence on the organization. He told a

Wall Street Journal

reporter: “After cursing the UN or calling it irrelevant or comparing it to the League of Nations and stating loud and clear that the United States would pay no attention to the Security Council in the future if it didn’t support the United States in its war against Saddam Hussein, the United States very quickly came back, even though they will never admit it, in search for international legitimacy, realizing that they can’t really act on their own too long.”

54

He continued: “I don’t have a crystal ball, but my guess is that the U.S. and the UK will realize that this is too big, that building a democratic Iraq is not simple . . . and as a result they have every interest in encouraging others who are seen to be more impartial, independent, more palatable to join in and help create these new institutions. . . . We will then look back at the war as an interlude that will have lasted two or three months, that was indeed shocking and did shake us a great deal, but nothing more than that: an accident rather than a new pattern . . . and I touch wood when I say that.”

55

Wall Street Journal

reporter: “After cursing the UN or calling it irrelevant or comparing it to the League of Nations and stating loud and clear that the United States would pay no attention to the Security Council in the future if it didn’t support the United States in its war against Saddam Hussein, the United States very quickly came back, even though they will never admit it, in search for international legitimacy, realizing that they can’t really act on their own too long.”

54

He continued: “I don’t have a crystal ball, but my guess is that the U.S. and the UK will realize that this is too big, that building a democratic Iraq is not simple . . . and as a result they have every interest in encouraging others who are seen to be more impartial, independent, more palatable to join in and help create these new institutions. . . . We will then look back at the war as an interlude that will have lasted two or three months, that was indeed shocking and did shake us a great deal, but nothing more than that: an accident rather than a new pattern . . . and I touch wood when I say that.”

55

Nineteen

“YOU CAN’T HELP PEOPLE FROM A DISTANCE”

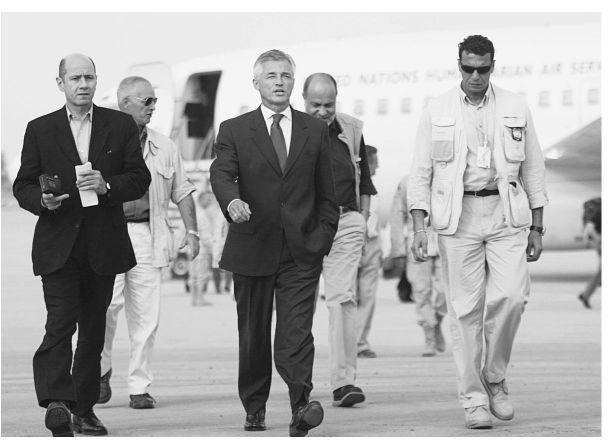

Vieira de Mello, bodyguard Gamal Ibrahim (

right

), and UN spokesman Ahmad Fawzi (

left

) at the Baghdad airport, June 2, 2003.

right

), and UN spokesman Ahmad Fawzi (

left

) at the Baghdad airport, June 2, 2003.

Vieira de Mello knew little about Iraq but a lot about helping societies that were emerging from tyranny and conflict. He understood that, on such a short mission, it was even more essential than usual to assemble the best possible team. Before leaving New York, he asked Rick Hooper, the American Arabic-speaking political analyst, and Salman Ahmed, an American who had been Lakhdar Brahimi’s aide in Afghanistan, to work with his own special assistant Jonathan Prentice to assemble an “A team.” “I want Arabic speakers,” he said, “and I want my team members to be with me when I get off the plane.” He needed to establish momentum right away.

Among the Arabic speakers he tapped were Nadia Younes, an Egyptian who had been Bernard Kouchner’s chief of staff in Kosovo; Jamal Benomar, a Moroccan lawyer who before joining the UN had been jailed for eight years in his country as a human rights activist; Ahmad Fawzi, an Egyptian who had been Brahimi’s spokesman during Afghanistan’s Bonn Conference; Mona Rishmawi, a Palestinian human rights officer; and Jean-Sélim Kanaan, a French-Egyptian veteran of Kosovo who had a reputation as a master logistician and acute political operator. Among the others he brought, in addition to Prentice and Ahmed, were Fiona Watson, a Scottish political officer who had been working on Iraq issues from New York; Carole Ray, his British secretary in Geneva; and Alain Chergui and Gamal Ibrahim, who had been his bodyguards in East Timor. Because Vieira de Mello offered his friend Dennis McNamara a seat on his plane, McNamara found himself named UNHCR special envoy to Iraq.

Vieira de Mello was not one to take no for an answer. He had made an art form out of teasing, flattering, and pressuring to get what he wanted. When Lyn Manuel, who had been his secretary in New York and East Timor, initially declined his offer, on the grounds that her daughter was getting married, he kept pushing. When she finally accepted, her supervisor in New York refused, but Vieira de Mello got Iqbal Riza, Annan’s chief of staff, to overrule him. He believed that UN staff should by definition be readily available to undertake any field mission at any time, in much the same way he was. And he used the same argument with junior and senior staff that he knew Annan would have made to him, had he refused the job: The mission was important for Iraq and for the UN, and their services were indispensable. Vieira de Mello had accepted the job on May 22, 2003, the day Resolution 1483 had been passed. He stopped off in Cyprus for briefings on June 1, and would fly with his team to Baghdad the following day.

He knew that his most important choice would be his political adviser. On the advice of Riza, he met in Cyprus with Ghassan Salamé, a former Lebanese minister of culture and professor of international relations at the prestigious Institut d’études politiques (Sciences Po) in Paris. Salamé had studied the politics and history of Iraq and had long been acquainted with leading Iraqi opposition officials and intellectuals, as well as members of the Ba’ath regime. His book,

Democracy without Democrats,

and his occasional columns in the pan-Arab daily newspaper

al-Hayat

had been banned in Iraq, but his name was known.

Democracy without Democrats,

and his occasional columns in the pan-Arab daily newspaper

al-Hayat

had been banned in Iraq, but his name was known.

At their meeting in Cyprus, Vieira de Mello said: “I don’t know much about Iraq. I need to pick your brain on who’s who, and how the country is moving.” Salamé warned that the influence of Iraq’s neighbors was going to increase and not diminish in the coming months, and he said that by deciding to demobilize an army of more than 400,000 soldiers, the Americans had committed “hari kari.”

1

After two hours of discussion it was clear that they clicked. Salamé had opposed the war, but he wanted to do what he could to help the UN end the Coalition’s occupation.

1

After two hours of discussion it was clear that they clicked. Salamé had opposed the war, but he wanted to do what he could to help the UN end the Coalition’s occupation.

On the flight from Cyprus to Baghdad on June 2, Vieira de Mello wore a finely tailored gray suit, a crisp starched white shirt, and an emerald green Ferragamo tie (“the color of Islam,” he said), given to him on his birthday by Larriera, who was getting her paperwork sorted and would join him on June 15. He had grown very sentimental. In his briefcase he carried the paper hearts that he had cut up in East Timor and sprinkled on the floor on the night they got back together in 2001.

He characteristically used the plane ride to study his only real instructions from the major powers: Resolution 1483. He focused on its provision “stressing the right of the Iraqi people freely to determine their own political future.” The resolution did not stipulate what the UN would do to make that happen. After exercising absolute power in East Timor, he was unaccustomed to the helping verbs that defined his functions. In Iraq it would not be up to him to devise laws or political structures; he would “encourage” and “promote” measures to improve Iraqi welfare. This meant that he would make inroads only insofar as the Coalition accepted his advice.“I think I could just as easily ‘encourage’ progress from Geneva,” he joked.

The UN mandate was awkward to say the least. Instead of negotiating with the local government, as UN officials usually did in countries where they deployed, his team would have to negotiate with the invaders, who had dismantled local structures. He knew that a large part of what he was there to do was to stress publicly and repeatedly that the day of Iraqi self-rule was near.

Before the group left Cyprus, Prentice had printed up a dozen copies of the draft statement he would deliver on the tarmac upon landing. On the plane each UN official offered his or her suggested changes, and Vieira de Mello incorporated half a dozen of them. The statement seemed relatively pro forma, and some on the plane were puzzled by his perfectionism. “For a three-minute speech, it seemed excessive to scrutinize and rescrutinize every clause,” remembers Fawzi, the spokesman. “But for Sergio it had to be just so.” Well practiced at descending into foreign lands, he had long understood what American planners had not adequately grasped before invading Iraq: Outsiders almost never get a second chance to make a first impression.

When the flight touched down in Baghdad, he disembarked from the plane. He had expected a large turnout, as the “return of the UN” was being widely hailed in the region and beyond. But when he stepped into the Baghdad heat, about a dozen journalists were on the tarmac to greet him. UN officials later learned that Paul Bremer had held his own press conference a short time before their arrival. After all of the intensity of the previous weeks, when the UN officials got off the plane and saw so few journalists, one recalls, “It felt like a bust.” As he disembarked, Vieira de Mello called Larriera in New York and insisted she turn on the television to watch his first press conference.

He spoke as meticulously as he dressed. He tucked his prepared text into his breast pocket and gave the appearance of speaking off the cuff: “The day when Iraqis govern themselves must come quickly,” he declared. “In the coming days, I intend to listen intensively to what the Iraqi people have to say.”

2

2

But when it came to reaching out to “the Iraqi people,” he was unsure where to start. He asked Prentice to pester Salamé, who was back in Paris, and to call him every day, sometimes several times a day. Vieira de Mello too would call. “Where are you?” he would ask. “Why aren’t you here?” Salamé explained that he could not simply zip off to Baghdad for a month. He was not a career UN civil servant who was accustomed to routinely disappearing on a moment’s notice. Vieira de Mello was unforgiving: “I need you. Iraq needs you.” Salamé succumbed to his new boss’s charm, but then the UN administrators failed him. “People keep calling me from all over the UN system,” he complained to Vieira de Mello. “Each of them has told me that they know I am going to Baghdad and need my details. But for all of the phone calls, I still don’t have an airplane ticket!” “Welcome to the UN,” said Vieira de Mello.

Salamé ended up arriving in Baghdad on June 9, exactly one week after the rest of the A team. It did not take long for the two men, who would become inseparable, to begin bantering. "Ghassan, straighten your tie,” Vieira de Mello would rib his unkempt adviser before their high-level meetings. Salamé smoked two cigars each day, and his new boss urged him to stop.“You don’t want to die young like my father,” he said. One month into the mission Salamé, whom Vieira de Mello had nicknamed “the

wazir,

” or minister, made motions to depart. “Of course you’re not thinking of leaving,” Vieira de Mello said. “The universities in Paris don’t start until October, so we will leave together,

wazir.

”

wazir,

” or minister, made motions to depart. “Of course you’re not thinking of leaving,” Vieira de Mello said. “The universities in Paris don’t start until October, so we will leave together,

wazir.

”

One vital source of experience in the country was the UN humanitarian coordinator in Iraq, Ramiro Lopes da Silva. Lopes da Silva had lived in Baghdad from 2002 until just before the Coalition invasion, and he had led the first UN mission back to Iraq on May 1. He had been a member of Vieira de Mello’s ten-day assessment mission in Kosovo in 1999, and as native Portuguese-speakers, they shared a cultural bond. There was so much work to be done that the labor could be divided naturally between humanitarian and reconstruction tasks, which Lopes da Silva managed, and political tasks, which Vieira de Mello oversaw. Lopes da Silva would continue coordinating the work of the humanitarian agencies and would develop a plan for liquidating the Oil for Food Program.

3

Vieira de Mello, who preferred high politics to “grocery delivery,” would work with the Coalition to try to speed the end of the occupation. He had somehow to earn the trust of the Iraqis and develop a strong working relationship with the Coalition. He knew that suspicious Iraqis, who were angry about a spike in violent crime and the seeming permanence of American rule, would not necessarily see these tasks as complementary.

3

Vieira de Mello, who preferred high politics to “grocery delivery,” would work with the Coalition to try to speed the end of the occupation. He had somehow to earn the trust of the Iraqis and develop a strong working relationship with the Coalition. He knew that suspicious Iraqis, who were angry about a spike in violent crime and the seeming permanence of American rule, would not necessarily see these tasks as complementary.

Other books

Beautiful Sins: Leigha Lowery by Jennifer Hampton

Lie by Night: An Out of Darkness novel (Entangled Ignite) by Marlowe, Cathy

Spring Perfection by DuBois, Leslie

My Charming Valentine by Maggie Ryan

Spider Lake by Gregg Hangebrauck

La condesa sangrienta by Alejandra Pizarnik, Santiago Caruso

Beyond Tears: Living After Losing a Child by Rita Volpe

Cobwebs by Karen Romano Young

The Curse of the Dragon God by Geoffrey Knight

A Plague of Poison by Maureen Ash