Chasing Aphrodite (25 page)

Authors: Jason Felch

Munitz knew that, months after opening the $1 billion-plus show palace, his talk of austerity would be greeted derisively by the staff. But he was remarkably tone-deaf to their reactions. His hearing was tuned instead to board members, who felt that Williams had let costs get out of hand while building the Getty Center. Time and again, the Getty had dipped into its endowment to make up the difference. Munitz took a cue from board chair Robert Erburu, CEO of Times Mirror and a trustee of the Huntington, a library and museum complex in San Marino, California, which had burned through money from a neglected endowment left by railroad baron Henry Huntington in 1927. Both Munitz and Erburu were determined not to make the same mistake in Brentwood.

Munitz began retrenching. After setting up peer-review committees to evaluate how each unit was performingâsomething many insiders considered a Darwinian exercise, pitting Getty employees against one anotherâMunitz disbanded the Information and Education institutes, considered the weakest of the bunch. Other programs faced cuts.

The only Getty enterprise excused from scrutiny was the museum, where allegiance to Williams had been the weakest. Museum director John Walsh had openly clashed with Williams over the years. Munitz seized on that poorly concealed animosity, allowing Walsh to ride out his time to retirement in the newly created post of trust vice president. The CEO then threw his support behind Walsh's deputy and confidante, Debbie Gribbon, to take over as museum director.

A tall strawberry blonde with a sharp mind and acid wit, Gribbon came from a family of overachievers. Her father was a prominent Washington, D.C., attorney, and her sister was a high-ranking U.S. appeals court judge, widely considered a possible candidate for the Supreme Court. Gribbon had earned her Ph.D. in fine arts at Harvard and was a curator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston when Walsh recruited her to the Getty in 1984, shortly after his own appointment. Although she could be charming, even disarmingly vulnerable, Gribbon had the instincts of a tiger when it came to protecting her turf.

Some board members were dubious about Gribbon's appointment. They wanted a nationwide search for a better-known, more widely respected replacement. Others doubted whether Gribbon was ready for the job. There was also the matter of her personal life. As Walsh's deputy, Gribbon had carried on a yearlong affair with drawings curator George Goldner, who was junior in rank but reported directly to Walsh. The affair, which was an open secret, ended in 1991. Goldner soon moved to New York City, but Walsh agreed to let him keep running his department by commuting to Malibu twice a month. In 1993, he left the Getty for a job at the Met.

The episode would have remained a quiet part of the Getty's institutional lore except that Gribbon ended up tangling with Goldner's successor, Nicholas Turner. She demoted him over allegations that he had sexually harassed his secretary. Turner left for another job, and the episode was forgottenâuntil days before the Getty Center opening, when Turner struck back. He filed a defamation lawsuit accusing Gribbon of trying to sabotage his career and characterizing his indiscretion as part of a sexually charged Getty culture. As evidence, he cited Gribbon's affair with Goldner. Scrambling to keep the charges quiet, trust officials negotiated a $650,000 settlement with Turner. One of Munitz's first acts as CEO was to approve the settlement, which spared Gribbon public humiliation but left a bad taste in the mouths of trustees.

Now hoping to promote her to museum director, Munitz argued that Gribbon should be forgiven. The board should move on. He assured trustees that she was ready to head the museum and warned that the Getty risked losing her to a competing institution if it dithered. Eventually, board members backed down, figuring they should let their new CEO have his way.

Gribbon's appointment was a political victory for Munitz. In the same vein, he sought to reshape the board itself. He soon found an opening through Barbara Fleischman.

In January 1997, Larry Fleischman had a fatal heart attack in London. The Getty held a memorial service for him, and at Barbara's request, Harold Williams accelerated payment on the antiquities acquisition, costing the trust an extra $2 million. Since then, Barbara had heard nothing from Malibu, a silence that offended the longtime socialite and Met trustee, who understood the necessity of maintaining close ties with donors.

When True passed word to Munitz that Fleischman was peeved, the gregarious CEO swung into action. With a 1999 board meeting scheduled in New York around the time of Fleischman's birthday, Munitz arranged to throw a lavish party for the widow at the Four Seasons Hotel. He also invited her to speak to trustees about how the Getty could improve its poor record of raising outside money. Fleischman urged trustees to capitalize on the villa renovation by organizing a "Villa Council" made up of donors willing to give $5,000 a year in exchange for special perks, ranging from previews of exhibits to going on summer antiquities tours arranged by True. Getty trustees were so charmed by Fleischman's enthusiasm that they put her name on a short list of candidates for upcoming board vacancies. They also voted to waive their mandatory retirement age so that the seventy-four-year-old donor could be eligible.

Fleischman was sworn in as a trustee at the June 2000 board meeting, which fell on an unexpectedly chilly day in Malibu. Munitz was triumphant, believing that he had sent a clear signal down the line that he was serious about cultivating and rewarding donors. It was also a sign to the rest of the museum world that the Getty, once thought to be above such things, was ready to woo and reward generous patrons.

Gribbon's appointment was announced at the same meeting, but the circumstances proved less felicitous. Minutes before Gribbon showed up glowingâhand in hand with her husband, a UCLA psychiatry professorâa fax from Nicholas Turner's attorneys had come through to the general counsel's office. The former curator was preparing a second lawsuit accusing the Getty of reneging on its earlier settlement agreement, which not only paid him money but also allowed him to question the collecting acumen of Gribbon's former lover, Goldner, in an upcoming Getty journal. The Getty had changed its mind about publishing Turner's comments after Goldner had caught wind of the article and threatened a lawsuit of his own.

Rather than have the entire mess, including Gribbon's affair, blow up in public, Munitz recommended paying Turner another $450,000. In the end, the Getty paid Turner $1.1 million to spare its new museum director embarrassment.

B

ETWEEN THE PROMOTION

of Gribbon and the appointment of Fleischman, True came out ahead. While Gribbon, an enemy, seemed to have greater authority to derail the curator's crusade against looted antiquities, Fleischman, an ally, now had the institutional clout to give the curator political protection from above.

The same month the board approved Gribbon and Fleischman, True took her reformist message to the Association of Art Museum Directors' annual meeting in Denver. The theme of the gathering was "Who Owns Our Collections?"

As she had at the Cultural Property Advisory Committee's meeting in Washington, True dismissed fears within the museum world that accepting reforms would open the floodgates to new claims that could empty the shelves of American museums. The museum community had long used arguments that were "distorted, patronizing and self-serving," she said, singling out for criticism the popular mantra among curators that unprovenanced objects were innocent until proven guilty. "Experience has taught me that in reality, if serious efforts to establish a clear pedigree for the object's recent past prove futile, it is most likelyâif not certainâthat it is the product of the illicit trade and we must accept responsibility for this fact," True said. "It has been our unwillingness to do so that is most directly responsible for the conflicts between museums, archaeologists and the source countries."

It was a remarkable denunciation. With these few words, she had exposed the rationalization American museums had used for decades.

The date was June 1, 2000. The next day, in a courthouse halfway around the world, a Swiss judge ruled that Italy could take possession of the contents of Giacomo Medici's warehouse. Soon after, two trucks filled with crates of photos, artifacts, and documents began the journey to the Villa Giulia in Rome. As soon as they arrived, Paolo Ferri began building a criminal case that would lead him to Marion True.

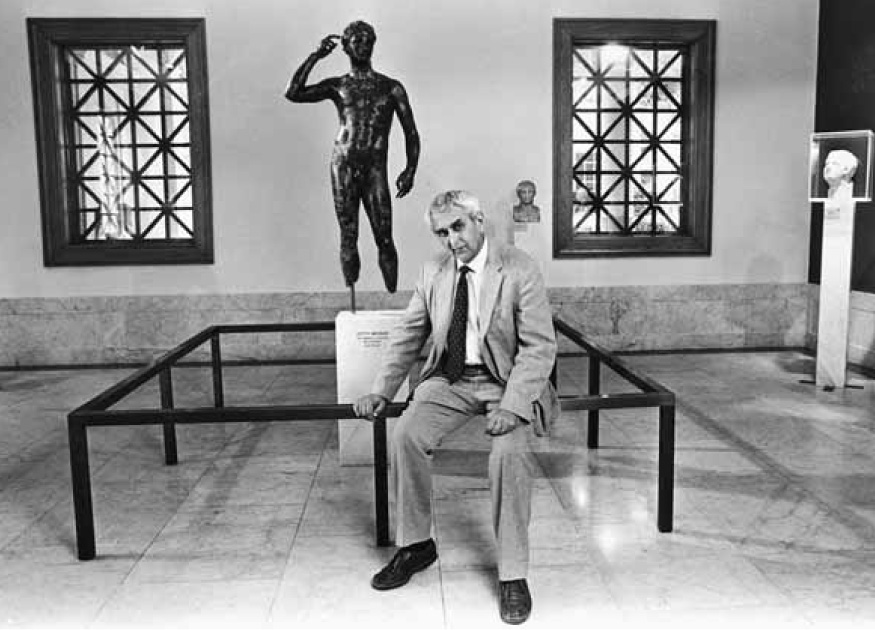

Oil tycoon J. Paul Getty was a millionaire with a miser's heart. He considered ancient art an addiction he could not shake. When Getty died in 1976, he left most of his personal wealth to his small museum in Malibu, making it the world's richest art institution overnight.

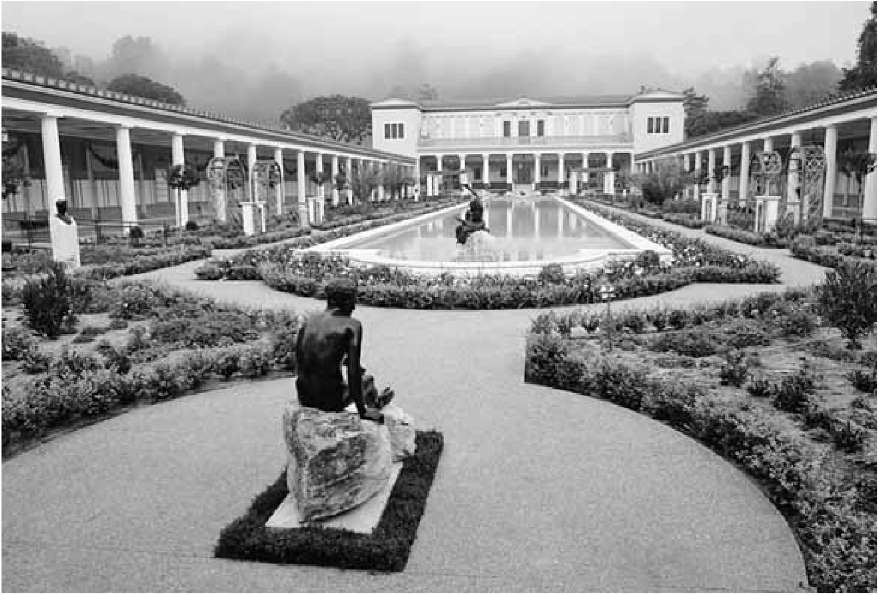

The reflecting pool and garden of the Getty Villa, which first opened in 1974. It was extensively remodeled and reopened in 2006 as the home of the Getty Museum's world-class antiquities collection. Soon after, many of the Getty's prized objects on display there were returned to Italy.

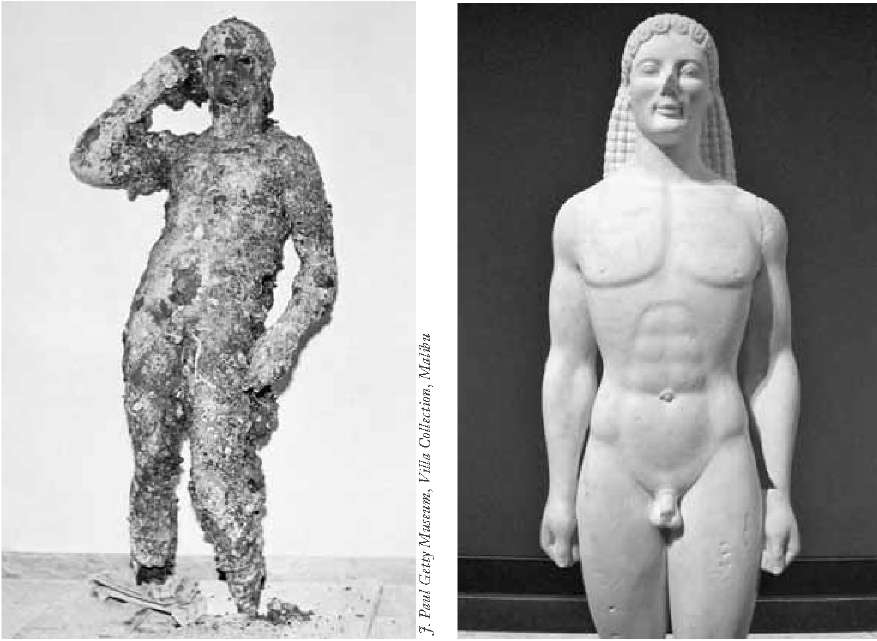

LEFT:

A photo of the Getty Bronze soon after it was hauled out of the Adriatic Sea in the 1960s by Italian fishermen. The statue was buried in a cabbage field and smuggled out of Italy before resurfacing in Europe in the 1970s, when J. Paul Getty first saw it.

RIGHT:

The kouros, or statue of a young man. The Getty bought the marble Greek statue for nearly $10 million in 1985, believing it was authentic and had been looted recently from southern Italy. After a lengthy investigation, many at the Getty concluded the kouros was a fake. Today it remains on display, labeled, "Greek, about 530

BC

or modern forgery."

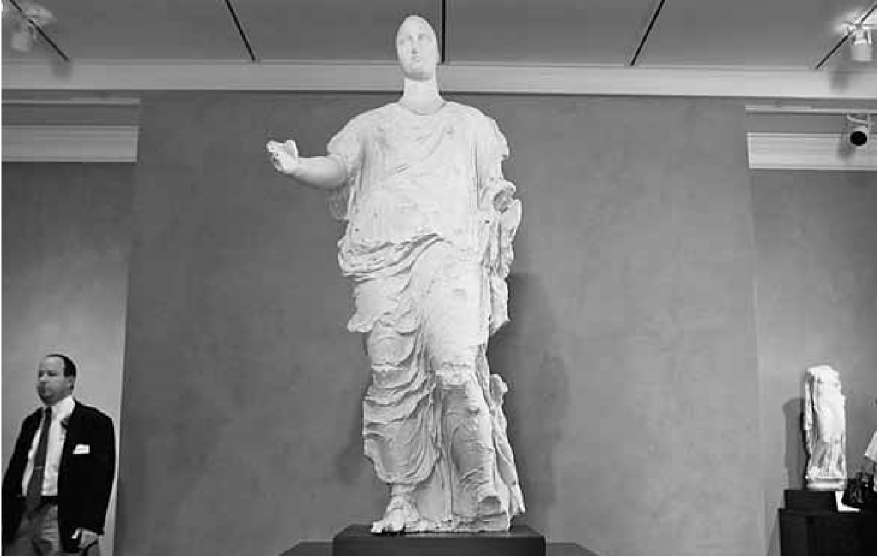

The Getty's Aphrodite, which the museum purchased in 1988 despite obvious signs it was looted. For the Italians, the towering figure became a symbol of cultural plunder fueled by American museums.