Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War (59 page)

Read Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War Online

Authors: Max Hastings

Tags: #Ebook Club, #Chart, #Special

But by far the most important event of 6 September was Kluck’s response to Manoury’s attacks. The German commander shifted men fast from his left, in front of the BEF, which was doing nothing to inconvenience him, to reinforce the threatened sector. On 5 September, Kluck’s formations held a west–east front. By the close of the 6th, his army was redeploying on a north–south line, and he was counter-attacking Manoury fiercely. The fact that he felt able to do so reflected a shameful British failure of will, potentially disastrous for the allied cause. The people of

France hung in suspense, knowing that a great battle was being fought, but utterly ignorant of its progress. One man wounded in the early clashes described his reception on arriving in his home town of Grenoble aboard a hospital train: ‘It was extraordinary. Flowers, chocolate, wine … we were fêted like heroes, but we couldn’t answer the questions: “How far are the Germans from Paris?” “Are we on the retreat?” And the Grenoblers, like all of France, demanded to know: “What are the British doing?”’

What indeed? The leaders of the French army fulminated at the tardiness of the BEF on 6 September. Kluck’s reinforcements were marching pell-mell across their front, highly vulnerable to an energetic assault. But the British had started the day ten miles behind their allies, and thereafter advanced with painful sluggishness. Lt. Lionel Tennyson’s only comment on his unit’s leisurely march that day, while the French on both sides were fighting for their lives, was: ‘we passed Jimmy Rothschild’s beautiful house, and saw masses of pheasants running about everywhere, and longed to be able to stop and get some’.

That afternoon the Rothschilds’ English gamekeeper surprised in a shed on the estate Pte. Thomas Highgate of the Royal West Kents, who had made a personal decision that the glories of the Marne offensive were not for him: he was clad in stolen civilian clothes, which damned him. Highgate was shot by firing squad on 8 September, a ceremony watched by two companies of his comrades, in accordance with a directive from Horace Smith-Dorrien. Straggling, trending towards desertion, was a serious problem: the corps commander wanted the execution to have the maximum possible deterrent effect. Orders to the provost-marshal specified that Highgate should be killed ‘as publicly as possible’, and so he was.

On 6 September, for some hours Sir Douglas Haig halted his own corps’ advance in the face of vague reports of enemy forces ahead. He thus ended the day seven miles short of his objectives, having lost just seven men killed and forty-four wounded. In the wasteful way of war, British sappers who had demolished a big stone bridge at Frilport only a few days earlier, during the retreat, now found themselves obliged to build a new river crossing to enable the infantry to retrace their steps. The most exciting thing to befall pilots of the RFC billeted in a girls’ school on 6 September was that they donned the pupils’ nightgowns over their uniforms and staged an epic pillow-fight. Next day, Monday the 7th, while Manoury’s army on their left sought to resume its offensive, in torrential rain the BEF marched just fourteen miles, and once again fought scarcely at all.

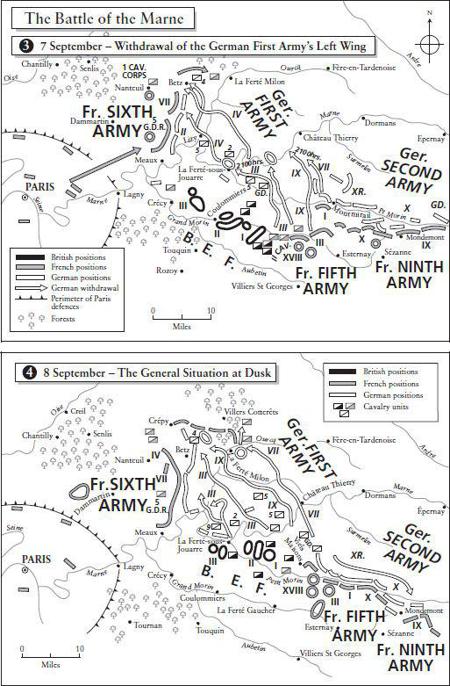

Alexander Johnston, a brigade signals officer in II Corps, wrote in bewilderment: ‘We did not start till 5 p.m. I cannot understand this. Surely our duty is according to Field Service Regulations “not to spare man or horse or gun in pursuing the enemy etc” … Heard that, had our 1st Corps pushed a bit more, we ought to have cornered those Germans last night.’ Marwitz’s cavalry rearguard mounted a succession of harassing actions which were entirely successful in reducing the British advance to a crawl. It seems fair to assert that, in accordance with the wishes of their C-in-C, the British were present in body during the critical days of the Marne, but absent in spirit. All the armies dispatched streams of signals to the rear protesting about the exhaustion of their respective soldiers, but it is striking to contrast the BEF’s casual progress with the speed of Kluck’s shift of front: his men marched almost forty miles on 7 September, more than forty miles on the 8th.

Meanwhile, the most famous legend of the battle is that of the Paris taxis which carried reinforcements to Manoury when his line was threatened with collapse by German counter-attacks. The number of men involved was, in truth, small, but the charm of the story endures. At the end of August, the French 7th Division had been moved north from Third Army in a nightmare rail journey from Sainte-Menehould: some trains took twenty-four hours to travel six miles around Troyes, where the network was clogged with supply trains, ambulance trains, refugee transport. The men were resting in billets at Pantin, a northern suburb of Paris, when Gallieni ordered them forthwith to join Sixth Army. Told that few military vehicles were available, the governor directed that civilian transport should be conscripted. A staff officer telephoned to the prefecture of police: ‘Have all taxis – without exception – returned to their depots. Instruct the taxi companies by telephone to have their vehicles supplied with petrol, oil, and, where necessary, tyres, and then sent immediately to the Esplanade des Invalides.’

Soon after 10 p.m., one of the longest columns of motor vehicles ever by that date assembled – four hundred, including a few private cars and twenty-four-seat open buses – set off to find its passengers. That first night, and the following day, proved anti-climactic. The staff officers charged with directing the convoy failed to locate the troops they were supposed to carry. The drivers, many of them old men, sat in the sun and waited hour after hour, watching cavalry and bicycle units pass en route to the front, and giving occasional encouraging cries: ‘

Vive les dragons!

’; ‘

Vive les cyclistes!

’

Only on the evening of the 7th did the taxis rendezvous with the 104th Infantry Brigade in the village of La Barrière. The troops were disbelieving when they discovered that they were to be carried to battle in taxis – most had never ridden in such luxury in their lives. But when they had clambered aboard, crammed in weapons and kit, through deep darkness the column set off for Sixth Army. The soldiers slept, like all soldiers at every opportunity, unless awakened by the clash of injured metal and the muted curses that accompanied minor collisions.

Paul Lintier was among Manoury’s men who witnessed the passage of the reinforcements through a village already crowded with men and horses. A vehicle ‘ploughing its way through the throng, forced a confused wave of men and beasts against me, the weight of which flattened me against the wall. Another car followed in its wake, then others and still others, in endless, silent procession. The moon had risen, and its rays reflected on the shiny peaks of taxi-drivers’ caps. Inside the cabs, one could make out the bent heads of sleeping soldiers. Someone asked, ‘Wounded?’ and a passing voice replied, ‘No, Seventh Division. From Paris. Going into the line …’ The passengers were finally decanted near Nanteuil. The ‘taxi-cabs of the Marne’ had carried 4,000 Frenchmen thirty miles, to play their part in a battle that embraced almost a million. The drivers, whose meters had been ticking throughout their odyssey, were paid a quarter of the amount shown, 130 francs, or around £5 sterling – at least a fortnight’s wages.

At 11.40 a.m. on 7 September, Franchet d’Espèrey issued a general order: ‘the enemy is in retreat along the whole front. The Fifth Army will make every effort to reach Petit Morin river [at Montmirail] tonight.’ That day, to their initial disbelief, his men found themselves advancing unopposed. The Germans in front of them had gone, marching north-west to confront Manoury’s offensive. Only Kluck’s dead remained. That night, Charles Mangin billeted himself in the Château de Joiselle, which the previous night had been occupied by Duke Günther of Schleswig-Holstein, the Kaiser’s brother-in-law. Louis Maud’huy hoped to find matching comforts in the château of Saint-Martin du Boschet, where lights were showing. But he arrived to discover the building crowded with German wounded, accompanied by a few medical orderlies who snapped to attention. ‘Bad luck!’ muttered the general, closing the door behind him as he left. ‘Never mind. I suppose there’s a barn somewhere?’ He and his staff slept on straw that night.

Further east, on the front of Foch’s Ninth Army, the fighting in the marshes of Saint-Gond continued as bitterly as ever. French 75s halted Bülow’s attempts to advance, and on the morning of 7 September the German commander ordered a withdrawal behind the Petit Morin. To his left, however, Hausen decided that the French must be weak in his own sector – as indeed they were. The general’s army was reduced to 82,000 men, and he himself was semi-delirious, suffering a sickness which was later identified as typhus. But Hausen demanded the launch of an energetic new assault, heedless of losses, which should start in the early-morning darkness of 8 September. Two German Guards divisions advanced in silence until with a rush they overran the sleeping men of two regiments, bayoneting many hapless French soldiers where they lay. Survivors fled.

The Germans pressed on, and soon fell upon reserve units, also slumbering with arms piled and no guards posted. They too died or ran – one infantry regiment, bivouacked two miles behind the front, lost fifteen officers and six hundred men. Foch and his corps commanders awoke at dawn to discover that their entire right wing was collapsing, thousands of men flying in panic. His staff telephoned their southerly neighbours to seek assistance, and was told Fourth Army could do nothing. Instead, Foch agreed with Franchet d’Espèrey, on his left, that they should together attempt an attack on the opposite wing, in the hope of forcing the Germans to abandon their push.

At lunchtime, however, the situation was still desperate: the Germans had advanced eight miles since dawn, and nothing seemed capable of stopping them. A lieutenant of the Zouaves described how his battalion counter-attacked behind a giant officer named d’Urbal: ‘At the attack on Etrepilly he went forward with just a walking-stick, smoking his pipe. He absolutely refused to lie down. “A French officer isn’t afraid of Germans,” he said: and, a second later, he was shot through the head.’ The counter-attack failed. On Foch’s front, absolute disaster seemed imminent. And matters were no better in Sixth Army’s sector. At a critical moment, some infantry units broke and ran in the face of Kluck’s hammer blow. A colonel named Robert Nivelle, who became a brief and disastrous commander-in-chief later in the war, responded to the spectacle of the fleeing men by riding forward at the head of his own artillery battery, unlimbering their 75s and opening fire on the Germans at point-blank range. Some infantry rallied around his guns, which represented success, but unfortunately for the later interests of the French army Nivelle himself survived.

That day of the 8th, Gallieni drove personally to Manoury’s headquarters at Saint-Soupplets, though the sick old general suffered agonies on the rough road. ‘I have come to put your mind at rest,’ he said magnificently. ‘You are up against three German army corps, at least, and your advance has been checked. But don’t worry …’ He meant that Sixth Army was doing its job of pinning Kluck’s forces, while Franchet d’Espèrey and Foch made the critical thrusts, with token support from the BEF. That evening, Manoury promised to hang on somehow, until pressure elsewhere made Kluck’s position untenable.

But on 8 September the outcome of the battle, perhaps also of the war, still hung in the balance. Both sides found themselves faced with a succession of revolving doors – they advanced in one sector, only to find themselves driven back in another. The French Sixth and Ninth Armies were in acute peril. Kluck was convinced that by next day, he would have accomplished Manoury’s defeat. Foch’s artillery was in constant action, some guns firing a thousand rounds a day. His soldiers wavered – some displayed a marked unwillingness to accept orders to go forward. In the course of the Marne battles, there were several episodes in which entire French regiments broke and fled.

Spears tells a story of how he once found himself with Maud’huy when they encountered a firing squad leading a soldier to execution for his part in such a collapse: ‘Maud’huy gave a look, then held up his hand so that the party halted, and with his characteristic quick step went up to the doomed man. He asked what he had been condemned for. It was for abandoning his post.’ Maud’huy then explained to the soldier the importance of discipline, the necessity of example; how some men could do their duty without sanctions but others, less strong, needed to recognise the cost of failure. The soldier nodded. Maud’huy held out his hand and said: “Yours also is a way of dying for France.”’ The general motioned the party to proceed. Spears asserts that this exchange reconciled the prisoner to his fate, which seems unlikely. What is certain is that the French army found such examples essential, to induce others to hold the line in 1914.

Through 8 September Franchet d’Espèrey continued to batter at Bülow’s army, which was now under heavy pressure, its flanks exposed. The German commander began to pull in his right wing, widening the gap with his neighbour. Critically, and amazingly, communications between Bülow and Kluck, and between both generals and Moltke, had almost collapsed. Each German commander was fighting his own battle, in profound ignorance of what was happening elsewhere, and no guiding

hand was imposing coordination. Moltke learned from wireless intercepts that the BEF was advancing into the void between Kluck and Bülow, but he was befogged about the general situation. He also allowed himself to become alarmed by the threat to his lines of communication posed by the Belgians, who had briefly sortied from Antwerp on 25–26 August; and from a possible British descent on the Belgian coast.