Carrier (1999) (5 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

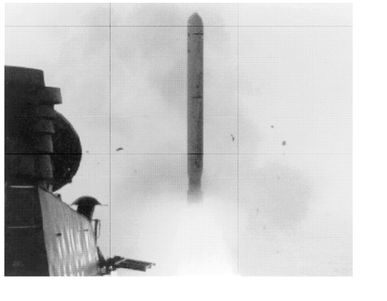

The launch of a BGM-109 Tomahawk cruise missile from the guided-missile destroyer

Laboon

(DDG-58) during Operation Desert Strike in 1996.

Laboon

(DDG-58) during Operation Desert Strike in 1996.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO

It goes without saying that institutions as large, diverse, and powerful as naval aviation do not just happen overnight. They evolve over time, and are the product of the forces and personalities that impact upon them. In fact, naval aviation grew to maturity surprisingly quickly, and most of the critical events and trends that shaped it happened in the roughly five decades stretching from 1908 through the mid-1950’s. During that time, the basic forms and functions that define carriers and their aircraft today were conceived and developed. Let’s take a look at a few of the most critical of these events and trends. We’ll start with the first act in the birth of the world’s most powerful conventional weapons system.

Eugene Ely’s StuntOur journey begins in 1908, just five years after the Wright brothers’ first flight, when Glenn Curtiss, an early aerial pioneer, laid out a bombing range in the shape of a battleship, and simulated attacking it. Though the U.S. Navy took notice of Curtiss’s test run, it took no action. Several years later, after word reached America of a German attempt to fly an airplane from the deck of a ship, the U.S. Navy decided to try a similar experiment. They built a wooden platform over the main deck of the light cruiser

Birmingham

(CL-2) and engaged Eugene Ely, a stunt pilot working for Curtiss, to fly off it. At 3 P.M. on the afternoon of November 14th, 1910, while

Birmingham

was anchored in Hampton Roads, Virginia, Ely gunned his engine, rolled down the wooden platform, and flew off. He landed near Norfolk several miles away. A few months later, Ely reversed the process and landed on another platform built on the stern of the armored cruiser

Pennsylvania

(ACR-4), which was then anchored in San Francisco Bay. Soon afterward, Congress began to appropriate money, the first naval aviators began to be trained, and planes began to go to sea with the fleet. It was a humble beginning, but Eugene Ely’s barnstorming stunt had started something very much bigger than that.

The First Flattop: The Conversion of the USSBirmingham

(CL-2) and engaged Eugene Ely, a stunt pilot working for Curtiss, to fly off it. At 3 P.M. on the afternoon of November 14th, 1910, while

Birmingham

was anchored in Hampton Roads, Virginia, Ely gunned his engine, rolled down the wooden platform, and flew off. He landed near Norfolk several miles away. A few months later, Ely reversed the process and landed on another platform built on the stern of the armored cruiser

Pennsylvania

(ACR-4), which was then anchored in San Francisco Bay. Soon afterward, Congress began to appropriate money, the first naval aviators began to be trained, and planes began to go to sea with the fleet. It was a humble beginning, but Eugene Ely’s barnstorming stunt had started something very much bigger than that.

Langley

(CV-1)

Stunts were one thing, but making naval aviation a credible military force was something else entirely. During World War I, U.S. naval aviation was primarily seaplanes used for gunnery spotting and antisubmarine patrols. However, the British achieved some fascinating results using normal (wheeled) pursuit aircraft (fighters) launched from towed barges, and later from specially built aircraft carriers converted from the hulls of other ships. These aircraft attacked German Zeppelin hangars and other targets.

6

The benefits of taking high-performance aircraft to sea were so obvious to the British that the Royal Navy rapidly set to converting further ships into aircraft carriers. This move did not go unnoticed by other Naval powers after World War I. By 1919, the Japanese were also constructing a purpose-built carrier, the

Hosho.

Meanwhile the British continued their program of converting hulls into aircraft carriers, and began work on their own from-the-keel-up carrier, the Hermes.

6

The benefits of taking high-performance aircraft to sea were so obvious to the British that the Royal Navy rapidly set to converting further ships into aircraft carriers. This move did not go unnoticed by other Naval powers after World War I. By 1919, the Japanese were also constructing a purpose-built carrier, the

Hosho.

Meanwhile the British continued their program of converting hulls into aircraft carriers, and began work on their own from-the-keel-up carrier, the Hermes.

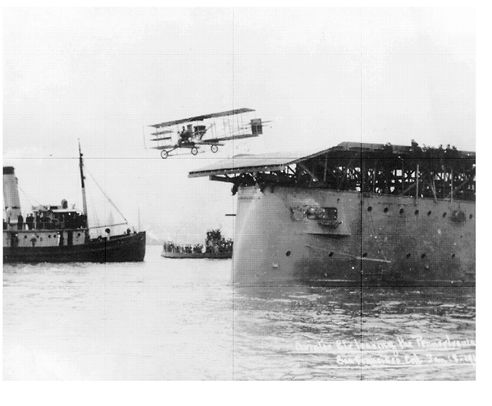

Eugene Ely flies off of the USS

Pennsylvania

at 3 P.M. on November 14th, 1910. This was the moment of birth for naval aviation.

Pennsylvania

at 3 P.M. on November 14th, 1910. This was the moment of birth for naval aviation.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO

These programs spurred the General Board of the U.S. Navy to start its own aircraft carrier program. In 1919, the board allocated funds to convert a surplus collier, the USS Jupiter, into the Navy’s first aircraft carrier, the USS

Langley

(CV-1)—nicknamed the “Covered Wagon” by her crew. For the next two decades, the little

Langley

provided the first generation of U.S. carrier aviators with their initial carrier training, and offered the fleet a platform to experiment with the combat use of aircraft carriers. When World War II arrived, the slow little ship was converted into a transport for moving aircraft to forward bases, and was sunk during the fighting around the Java barrier in 1942. However, the

Langley

remains a beloved memory for the men who learned the naval aviation trade aboard her.

The Washington Naval Treaty: The Birth of the Modern Aircraft CarrierLangley

(CV-1)—nicknamed the “Covered Wagon” by her crew. For the next two decades, the little

Langley

provided the first generation of U.S. carrier aviators with their initial carrier training, and offered the fleet a platform to experiment with the combat use of aircraft carriers. When World War II arrived, the slow little ship was converted into a transport for moving aircraft to forward bases, and was sunk during the fighting around the Java barrier in 1942. However, the

Langley

remains a beloved memory for the men who learned the naval aviation trade aboard her.

While the

Langley

was primarily a test and training vessel, her initial trials led the Navy leadership to build larger aircraft carriers that could actually serve with the battle fleet. The problem was finding the money to build these new ships. The early 1920’s were hardly the time to request funds for a new and unproved naval technology, when the fleet was desperately trying to hold onto the modern battleships constructed during the First World War. The solution came after the five great naval powers (the United States, Great Britain, Japan, France, and Italy) signed the world’s first arms-control treaty at the Washington Naval Conference of 1922. Though the treaty set quotas and limits on all sorts of warship classes, including aircraft carriers, a bit of fine print provided all the signatories with the opportunity to get “something for nothing.”

Langley

was primarily a test and training vessel, her initial trials led the Navy leadership to build larger aircraft carriers that could actually serve with the battle fleet. The problem was finding the money to build these new ships. The early 1920’s were hardly the time to request funds for a new and unproved naval technology, when the fleet was desperately trying to hold onto the modern battleships constructed during the First World War. The solution came after the five great naval powers (the United States, Great Britain, Japan, France, and Italy) signed the world’s first arms-control treaty at the Washington Naval Conference of 1922. Though the treaty set quotas and limits on all sorts of warship classes, including aircraft carriers, a bit of fine print provided all the signatories with the opportunity to get “something for nothing.”

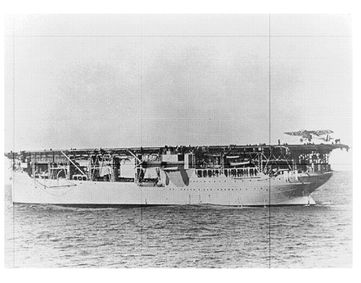

The USS

Langley

(CV-1), the U.S. Navy’s first aircraft carrier. She was converted from the collier

Jupiter.

She served as a floating laboratory for U.S. naval aviation into the 1930s, and was subsequently sunk in 1942 during the Battle of the Java Sea.

Langley

(CV-1), the U.S. Navy’s first aircraft carrier. She was converted from the collier

Jupiter.

She served as a floating laboratory for U.S. naval aviation into the 1930s, and was subsequently sunk in 1942 during the Battle of the Java Sea.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO FROM THE COLLECTION OF A. D. BAKER

At the end of the war, several countries were constructing heavy battleships and battle cruisers,

7

which were still unfinished in the early 1920’s. Meanwhile, the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty set limits on the maximum allowable displacement and gun size of individual ships, as well as a total quota of tonnage available to each signatory nation (the famous 5:5:3 ratio).

8

Even after scrapping older dreadnought-era battleships, the nations within the agreement were left with no room for building new battleships and battle cruisers (which were classed together because of gun size). However, the treaty allowed the signatories to convert a percentage of their allowable carrier tonnage from the hulls of the uncompleted capital ships. What made this especially attractive was that the new carriers could be armed with the same 8-in/203mm gun armament as a heavy cruiser. Thus, even if the aircraft carriers themselves proved to be unsuccessful, those heavy cruiser guns would still make the ships useful.

7

which were still unfinished in the early 1920’s. Meanwhile, the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty set limits on the maximum allowable displacement and gun size of individual ships, as well as a total quota of tonnage available to each signatory nation (the famous 5:5:3 ratio).

8

Even after scrapping older dreadnought-era battleships, the nations within the agreement were left with no room for building new battleships and battle cruisers (which were classed together because of gun size). However, the treaty allowed the signatories to convert a percentage of their allowable carrier tonnage from the hulls of the uncompleted capital ships. What made this especially attractive was that the new carriers could be armed with the same 8-in/203mm gun armament as a heavy cruiser. Thus, even if the aircraft carriers themselves proved to be unsuccessful, those heavy cruiser guns would still make the ships useful.

The British had already converted their tonnage quota with the

Furious, Courageous, Glorious,

and

Eagle,

while the Japanese converted their new carriers from the uncompleted battle cruiser

Akagi

and the battleship

Kaga.

The American vessels, however, were something special. The U.S. Navy wanted its two new carriers to be the biggest, fastest, and most capable in the world. The starting points were a pair of partially completed battle cruiser hulls. Already christened the

Lexington

and

Saratoga,

they were converted into the ships that the fledgling naval air arm had always dreamed of. When commissioned in 1927, the

Lexington

(CV-2) and

Saratoga

(CV-3) were not only the largest (36,000-tons displacement), fastest (thirty-five knots), most powerful warships in the world, (most important) they could operate up to ninety aircraft, twice the capacity of the Japanese or British carriers.

9

The

Lexington

and

Saratoga

also featured a number of new design features (such as the now-familiar “island” structures, which contained the bridge, flight control stations, and uptakes for the engineering exhausts), which greatly improved their efficiency and usefulness. The treaty-mandated gun turrets were placed in four mounts fore and aft of the island structure.

Furious, Courageous, Glorious,

and

Eagle,

while the Japanese converted their new carriers from the uncompleted battle cruiser

Akagi

and the battleship

Kaga.

The American vessels, however, were something special. The U.S. Navy wanted its two new carriers to be the biggest, fastest, and most capable in the world. The starting points were a pair of partially completed battle cruiser hulls. Already christened the

Lexington

and

Saratoga,

they were converted into the ships that the fledgling naval air arm had always dreamed of. When commissioned in 1927, the

Lexington

(CV-2) and

Saratoga

(CV-3) were not only the largest (36,000-tons displacement), fastest (thirty-five knots), most powerful warships in the world, (most important) they could operate up to ninety aircraft, twice the capacity of the Japanese or British carriers.

9

The

Lexington

and

Saratoga

also featured a number of new design features (such as the now-familiar “island” structures, which contained the bridge, flight control stations, and uptakes for the engineering exhausts), which greatly improved their efficiency and usefulness. The treaty-mandated gun turrets were placed in four mounts fore and aft of the island structure.

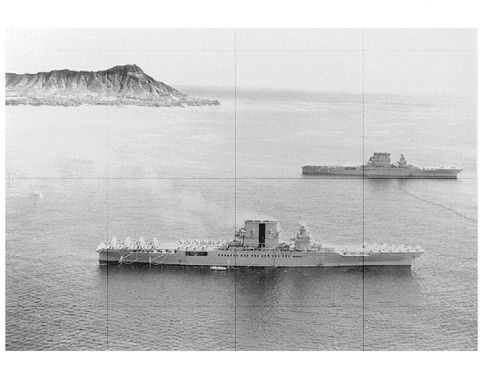

The aircraft carriers

Saratoga

(CV-3, in the foreground) and

Lexington

(CV-2, in the background) together near Diamond Head, Hawaii. At the time this was taken, the two converted battle cruisers were the largest, fastest, and most powerful warships in the world.

Saratoga

(CV-3, in the foreground) and

Lexington

(CV-2, in the background) together near Diamond Head, Hawaii. At the time this was taken, the two converted battle cruisers were the largest, fastest, and most powerful warships in the world.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO FROM THE COLLECTION OF A. D. BAKER

With the commissioning of the

Lexington

and

Saratoga

(and parallel rapid strides in naval aircraft design), the U.S. Navy took the world lead in naval aviation development. Virtually all of the American leaders who commanded carriers and air units during the Second World War served their early tours of duty aboard the two giant carriers. In addition, the series of fleet problems (war games) involving the

Lexington

and

Saratoga

led to the tactics America would take into the coming Pacific war with Japan.

The Taranto Raid and the Sinking of the BattleshipLexington

and

Saratoga

(and parallel rapid strides in naval aircraft design), the U.S. Navy took the world lead in naval aviation development. Virtually all of the American leaders who commanded carriers and air units during the Second World War served their early tours of duty aboard the two giant carriers. In addition, the series of fleet problems (war games) involving the

Lexington

and

Saratoga

led to the tactics America would take into the coming Pacific war with Japan.

Bismarck

Always leaders in the development of naval aviation technology and tactics, the British had planned for and assimilated the aircraft carrier into their fleet long before the opening of the Second World War. This was not merely institutional integration, for there were also plans for potential wartime carrier operations. One of these plans, devised in the 1930s, involved a surprise strike against the Italian battle fleet based at Taranto harbor in southern Italy: A carrier force would approach at night, launch torpedo bombers, and sink the Italian battleships at their moorings.

The opportunity to implement the plan came soon after the Italian declaration of war on Great Britain (in June of 1940) and the fall of France (later that summer). Despite the highly aggressive efforts of the British Mediterranean Fleet under their legendary commander, Fleet Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, the fleet was in trouble from the start. It was outnumbered and split by Fascist Italy, since the Italian peninsula more or less bisects the Mediterranean. By the fall of 1940, Italy had six modern battleships, while Cunningham only commanded a pair. His only real advantages were a few ships equipped with radar, the British intelligence ability to read Axis cryptographic (code and cipher) traffic, and a pair of aircraft carriers—the old

Eagle

and the brand-new armored deck flattop HMS

Illustrious.

Doing what he could to make the odds more even, Cunningham ordered his staff to plan a carrier aircraft strike on the Italian fleet base at Taranto. Though they had no real-world experience to work from, and only sketchy data from old fleet exercises about how to proceed, with typical British aplomb they began training aircrews and modifying their aerial torpedoes so they would run successfully in the shallow water of Taranto Harbor. Meanwhile, a special flight of Martin Maryland bombers began regular reconnaissance of Italian fleet anchorages. By November of 1940, they were ready to go with Operation Judgment.

Eagle

and the brand-new armored deck flattop HMS

Illustrious.

Doing what he could to make the odds more even, Cunningham ordered his staff to plan a carrier aircraft strike on the Italian fleet base at Taranto. Though they had no real-world experience to work from, and only sketchy data from old fleet exercises about how to proceed, with typical British aplomb they began training aircrews and modifying their aerial torpedoes so they would run successfully in the shallow water of Taranto Harbor. Meanwhile, a special flight of Martin Maryland bombers began regular reconnaissance of Italian fleet anchorages. By November of 1940, they were ready to go with Operation Judgment.

Other books

Clash of the Geeks by John Scalzi

Murder Mile High by Lora Roberts

Don't Order Dog by C. T. Wente

Croc's Return by Eve Langlais

Loving Che by Ana Menendez

Set This House on Fire by William Styron

Winds of the Storm by Beverly Jenkins

The Gift of Charms by Julia Suzuki

He Was Her Man by Sarah Shankman

His Golden Heart by Marcia King-Gamble