Carrier (1999) (41 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

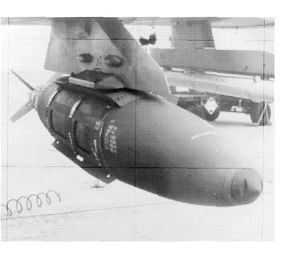

A testing version of the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) guided bomb. JDAM utilizes GPS technology to guide it within just a few yards/meters of the aimpoint.

BOEING MISSILE SYSTEMS

One key limitation of the current generation of LGBs and Imaging Infrared (IIR)-guided PGMs is that they do not perform well in poor weather. Water vapor and cloud cover are the enemies of these weapons and targeting systems, and have proven to be significant roadblocks to their employment. What airpower planners need is a family of true, all-weather PGMs. Creating this is the goal of the joint USAF/USN/USMC Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) program, which will go into service in 1999.

Now being developed by Boeing Missile Systems (formerly McDonnell Douglas Missile Systems), JDAM is designed to be a “strap-on” guidance kit, compatible with a variety of different bomb warheads. JDAM will be equipped with a GPS guidance system and control fins, which can fit around a conventional Mk. 83 (1,000-lb/454 kg), Mk. 84 (2,000-lb/909-kg), or BLU-109 (2,000 lb/909 kg) bomb. Since the JDAM will take its guidance from the constellation of GPS satellites in orbit around the earth, all you’ll need to designate a target will be the sixteen-digit numeric code that represents the target’s geographic location on the earth’s surface.

As currently planned, there will be four separate versions of the Phase I JDAM family. They include:

An F/A-18C Hornet armed with four AGM-154A Joint Standoff Weapons (JSOWs) during a test flight. JSOW is one of a family of precision-strike weapons guided by the NAVISTAR GPS satellite navigation system.

RAYTHEON STRIKE SYSTEMS

The majority of the JDAM acquisition will be composed of kits for the GBU-31 and -32 versions. These are sized to fit around both Mk. 83/84 general-purpose bombs, as well as BLU-109/110 penetration warheads. So far, the program is proceeding well in tests, and has proved to be quite accurate. The specified thirteen-meter/forty-three foot-accuracy (six meters/ twenty feet when the new Block IIR GPS satellites are put into service) is regularly being beaten in drop tests, and JDAM should come into service on schedule. At a price of only about $15,000 over the price of the bomb, JDAM is going to be quite a bargain. It needs to be, since current plans have the American military alone buying over 87,000 JDAM kits over the next decade or so. One intriguing question about JDAM is whether or not it will be fitted with an ATA-type seeker to enable it to hit really precise targets. While an ATA seeker would only add another $15,000 to the cost of each kit, the accuracy would narrow to less than three meters/ten feet—as good as the Paveway III LGBs in service today. I would expect that you would see an ATA-based seeker deployed on JDAM by 2003.

AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW)Well on its way into active service, the AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) is intended to be a munitions “truck” able to carry a variety of weapons and payloads.

63

Designed to glide to a target with guidance from an onboard GPS/INS system, it can deliver its payload with the same accuracy as a JDAM bomb. The initial AGM-154A version is armed with BLU-97 Combined Effect Munitions (CEMs), while the -B model will carry BLU- 108 Sensor Fused Weapons (SFWs) for attacking armor and vehicles. There are also plans for a -C model for the Navy, which will have a 500-lb/226.8-kg Mk. 82/BLU-111 unitary warhead as well as a man-in-the-loop data-link system similar to that on SLAM. An ATA-type seeker may also be fitted. This weapon is now officially operational with the fleet, with six -A models forward-deployed on the USS

Nimitz

(CVN-68) prior to the 1997 Iraq crisis, where they almost got their combat introduction.

AIM-9X Sidewinder Air-to-Air Missile63

Designed to glide to a target with guidance from an onboard GPS/INS system, it can deliver its payload with the same accuracy as a JDAM bomb. The initial AGM-154A version is armed with BLU-97 Combined Effect Munitions (CEMs), while the -B model will carry BLU- 108 Sensor Fused Weapons (SFWs) for attacking armor and vehicles. There are also plans for a -C model for the Navy, which will have a 500-lb/226.8-kg Mk. 82/BLU-111 unitary warhead as well as a man-in-the-loop data-link system similar to that on SLAM. An ATA-type seeker may also be fitted. This weapon is now officially operational with the fleet, with six -A models forward-deployed on the USS

Nimitz

(CVN-68) prior to the 1997 Iraq crisis, where they almost got their combat introduction.

For almost a decade, the fighter pilots of the United States have been flying with a short-range AAM that has been thoroughly outclassed by competing products from Russia, Israel, and France. Despite its past successes, the third-generation AIM-9L/M Sidewinder AAM has been passed by and is now thoroughly outclassed. Help is on the way however, in the form of a new fourth-generation Sidewinder, the AIM-9X. Built by Raytheon-Hughes Missile Systems, it will become operational in 1999. The changes in the AIM- 9X start at the seeker head, which will be a “staring” IIR array, able to detect targets at ranges beyond those of the human eye. A new guidance and control section at the rear of the missile will make it the most maneuverable AAM in the world. Reduced drag will also extend its range and “no-escape” zone for enemy target aircraft. Finally, the entire AIM-9X system will be controlled by a new helmet-mounted sighting system, which will first see service in the Super Hornet (but it will also be fitted on the Tomcat and earlier-model Hornets). This new missile will be so maneuverable that an AIM-9X can be fired at enemy aircraft that are

alongside

the launching aircraft!

Thealongside

the launching aircraft!

Real

Future: Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles

Even as the JSF designs are being finalized and the eventual winner selected, it is important to remember that Lockheed Martin and Boeing can’t engineer out the nature of the humans that will fly it. Right now, combat aircraft require their air crews to endure dynamic forces that are nothing less than physical torture. At times these stresses can turn deadly. The rapid onset of G-forces in sharp turns literally drains the blood from pilots’ heads, causing a sudden “G-Induced Loss-of-Consciousness,” or G-LOC. This means that there is a limit to the performance engineers can put into new aircraft—the physical limitations of the human pilots.

A flight of Lockheed Martin Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle (UCAV) concept aircraft. Such remote-controlled aircraft will likely serve in the mid-21st century.

LOCKHEED MARTIN

With this in mind, it is likely that the generation of combat aircraft

after

JSF will be unmanned. Today, in roles like photo-reconnaissance and wide-area surveillance, a great deal is already being done with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Back in the 1970’s there were even trials with armed drones, though the threat to pilot billets put short work to that idea. Even so, they make a lot of sense—if not today, then tomorrow. What will be known as Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles, or UCAVs for short, will probably start out as modified existing designs (such as leftover F-16’s or F/A-18’s) whose cockpits will be filled with sensors and data links back to the operators on the ground. In fact, a modified F/A-18C would make an excellent first-generation UCAV, since it already can conduct automatic carrier landings.

after

JSF will be unmanned. Today, in roles like photo-reconnaissance and wide-area surveillance, a great deal is already being done with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Back in the 1970’s there were even trials with armed drones, though the threat to pilot billets put short work to that idea. Even so, they make a lot of sense—if not today, then tomorrow. What will be known as Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles, or UCAVs for short, will probably start out as modified existing designs (such as leftover F-16’s or F/A-18’s) whose cockpits will be filled with sensors and data links back to the operators on the ground. In fact, a modified F/A-18C would make an excellent first-generation UCAV, since it already can conduct automatic carrier landings.

The aircraft would fly and operate conventionally, with the exception that when high-G maneuvers are needed, the 9-G limit in the flight-control software could be disabled and the UCAV flown to the actual structural limits of the design. Since we already have in service AAMs that make thirty-G turns, we could easily produce combat aircraft with performances that would make manned aircraft obsolete overnight. UCAVs would doubtless also be much cheaper than current designs, since so much of the money in a manned aircraft design goes into making it safe for the pilot and crew to operate. Keep an eye on this emerging technology. It will be exciting!

Carrier Battle Group: Putting It All Together

A

ircraft Carrier Battle Groups (CVBGs) are the single most useful military force available in time of crisis or conflict. No other military unit, be it an airborne brigade or a wing of strategic bombers, gives the leadership of a nation the options and power that such a force commands. This is because the

real

value of CVBGs goes far beyond the simple existence of the unit and its availability for combat; CVBGs also provide

presence.

America’s forward-deployed battle groups in the Middle East and the Western Pacific are the most visible symbol of the nation’s global commitments. Because of these battle groups, our nation has a say in the affairs of nations and people who threaten

our

vital national interests. The commander of such a battle group bears an awesome responsibility.

ircraft Carrier Battle Groups (CVBGs) are the single most useful military force available in time of crisis or conflict. No other military unit, be it an airborne brigade or a wing of strategic bombers, gives the leadership of a nation the options and power that such a force commands. This is because the

real

value of CVBGs goes far beyond the simple existence of the unit and its availability for combat; CVBGs also provide

presence.

America’s forward-deployed battle groups in the Middle East and the Western Pacific are the most visible symbol of the nation’s global commitments. Because of these battle groups, our nation has a say in the affairs of nations and people who threaten

our

vital national interests. The commander of such a battle group bears an awesome responsibility.

Rear Admiral Jay Yakley was one of those commanders. He’s gone from flying fighters in Vietnam to commanding his own aircraft carrier battle group (CVBG), based around the USS

Abraham Lincoln

(CVN-72). Back in the early days of August 1990, he was the one of the point men facing down the forces of Saddam Hussein following the invasion of Kuwait. As commander of Carrier Air Wing Fourteen (CVW-14) aboard the USS Indepen

dence

(CV-61), he was in charge of the first organized combat air unit to reach the region following the invasion. In this capacity, together with roughly ten thousand other Americans of the

Independence

CVBG, he had the job of holding the line until other reinforcements could arrive.

Abraham Lincoln

(CVN-72). Back in the early days of August 1990, he was the one of the point men facing down the forces of Saddam Hussein following the invasion of Kuwait. As commander of Carrier Air Wing Fourteen (CVW-14) aboard the USS Indepen

dence

(CV-61), he was in charge of the first organized combat air unit to reach the region following the invasion. In this capacity, together with roughly ten thousand other Americans of the

Independence

CVBG, he had the job of holding the line until other reinforcements could arrive.

He did not have long to wait. Within days, Allied units began to pour in and form the core of the coalition that eventually liberated Kuwait and defeated Saddam’s forces. But for those first few days, Jay Yakley and his roughly ninety airplanes were the only credible aerial force that might have struck at Saddam’s armored columns, had they chosen to continue their advance into the oil fields and ports of northern Saudi Arabia. Only Hussein himself knows whether or not the

Independence

group was the deterrent that kept Saddam from invading Saudi Arabia.

Independence

group was the deterrent that kept Saddam from invading Saudi Arabia.

However, the ability to quickly move the

Independence

and her battle group from their forward-deployed position near Diego Garcia made it possible to demonstrate American resolve to the Iraqi dictator.

That

is the real point of aircraft carriers:

to be seen.

Once seen, they can cause an aggressor to show common sense and back off. But if the aggressor fails to show common sense, then the CVBG can act to make them back off with force.

Independence

and her battle group from their forward-deployed position near Diego Garcia made it possible to demonstrate American resolve to the Iraqi dictator.

That

is the real point of aircraft carriers:

to be seen.

Once seen, they can cause an aggressor to show common sense and back off. But if the aggressor fails to show common sense, then the CVBG can act to make them back off with force.

It is not just the obvious power of the carriers—or more particularly, of the aircraft that fly off them—that is the source of the options a CVBG provides national leadership. In fact, to look at a CVBG without seeing beyond the carrier is to look at an iceberg without seeing what lies submerged. The

real

power of a CVBG is far more than what the flattop with its air wing can bring to bear. Each CVBG is a carefully balanced mix of ships, aircraft, personnel, and weapons, designed to provide the national command authorities with an optimum mix of firepower and capabilities. That the group can be forward-deployed means that it has a presence wherever it goes, and that American leaders have options when events take a sudden or unpleasant turn on the other side of the planet. The downside is cost. CVBGs are among the most expensive military units to build, operate, train, and maintain; a country can only buy so many. Nevertheless, in the years since the end of the Cold War, CVBGs have demonstrated how very useful they can be on a number of occasions. Operations like Southern Watch (Iraqi no-fly patrols, 1991 to present), Uphold Democracy (Haiti, 1994), and Deliberate Force (Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1995) are only a few of these.

real

power of a CVBG is far more than what the flattop with its air wing can bring to bear. Each CVBG is a carefully balanced mix of ships, aircraft, personnel, and weapons, designed to provide the national command authorities with an optimum mix of firepower and capabilities. That the group can be forward-deployed means that it has a presence wherever it goes, and that American leaders have options when events take a sudden or unpleasant turn on the other side of the planet. The downside is cost. CVBGs are among the most expensive military units to build, operate, train, and maintain; a country can only buy so many. Nevertheless, in the years since the end of the Cold War, CVBGs have demonstrated how very useful they can be on a number of occasions. Operations like Southern Watch (Iraqi no-fly patrols, 1991 to present), Uphold Democracy (Haiti, 1994), and Deliberate Force (Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1995) are only a few of these.

Other books

The Queen and the Courtesan by Freda Lightfoot

Cross My Heart, Hope to Die by Sara Shepard

Running Hot by Jayne Ann Krentz

The Destiny of the Sword by Dave Duncan

Henry and Ribsy by Beverly Cleary

Playing for Keeps (Texas Scoundrels) by Denton, Jamie

Barbara Levenson - Mary Magruder Katz 03 - Outrageous October by Barbara Levenson

The Informant by Marc Olden

Dying Days 3 by Armand Rosamilia