Cargo of Coffins (14 page)

Authors: L. Ron Hubbard

Tags: #Education & Reference, #Words; Language & Grammar, #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #Sea Adventures, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Hard-Boiled, #Thrillers, #Men's Adventure, #Thriller, #sea adventure

Nevertheless, and needless to say, L. Ron Hubbard persevered and soon earned a reputation as among the most publishable names in pulp fiction, with a ninety percent placement rate of first-draft manuscripts. He was also among the most prolific, averaging between seventy and a hundred thousand words a month. Hence the rumors that L. Ron Hubbard had redesigned a typewriter for faster keyboard action and pounded out manuscripts on a continuous roll of butcher paper to save the precious seconds it took to insert a single sheet of paper into manual typewriters of the day.

L. Ron Hubbard, circa 1930, at the outset of a literary career that would finally span half a century.

That all L. Ron Hubbard stories did not run beneath said byline is yet another aspect of pulp fiction lore. That is, as publishers periodically rejected manuscripts from top-drawer authors if only to avoid paying top dollar, L. Ron Hubbard and company just as frequently replied with submissions under various pseudonyms. In Ron’s case, the list included: Rene Lafayette, Captain Charles Gordon, Lt. Scott Morgan and the notorious Kurt von Rachen—supposedly on the lam for a murder rap, while hammering out two-fisted prose in Argentina. The point: While L. Ron Hubbard as Ken Martin spun stories of Southeast Asian intrigue, LRH as Barry Randolph authored tales of romance on the Western range—which, stretching between a dozen genres is how he came to stand among the two hundred elite authors providing close to a million tales through the glory days of American Pulp Fiction.

A Man of Many Names

Between 1934 and 1950, L. Ron Hubbard authored more than fifteen million words of fiction in more than two hundred classic publications.

To supply his fans and editors with stories across an array of genres and pulp titles, he adopted fifteen pseudonyms in addition to his already renowned L. Ron Hubbard byline.

______

Winchester Remington Colt

Lt. Jonathan Daly

Capt. Charles Gordon

Capt. L. Ron Hubbard

Bernard Hubbel

Michael Keith

Rene Lafayette

Legionnaire 148

Legionnaire 14830

Ken Martin

Scott Morgan

Lt. Scott Morgan

Kurt von Rachen

Barry Randolph

Capt. Humbert Reynolds

In evidence of exactly that, by 1936 L. Ron Hubbard was literally leading pulp fiction’s elite as president of New York’s American Fiction Guild. Members included a veritable pulp hall of fame: Lester “Doc Savage” Dent, Walter “The Shadow” Gibson, and the legendary Dashiell Hammett—to cite but a few.

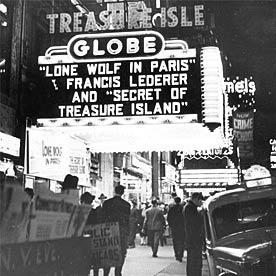

Also in evidence of just where L. Ron Hubbard stood within his first two years on the American pulp circuit: By the spring of 1937, he was ensconced in Hollywood, adopting a Caribbean thriller for Columbia Pictures, remembered today as

The Secret of Treasure Island.

Comprising fifteen thirty-minute episodes, the L. Ron Hubbard screenplay led to the most profitable matinée serial in Hollywood history. In accord with Hollywood culture, he was thereafter continually called upon to rewrite/doctor scripts—most famously for long-time friend and fellow adventurer Clark Gable.

The 1937

Secret of Treasure Island,

a fifteen-episode serial adapted for the screen by L. Ron Hubbard from his novel,

Murder at Pirate Castle

.

In the interim—and herein lies another distinctive chapter of the L. Ron Hubbard story—he continually worked to open Pulp Kingdom gates to up-and-coming authors. Or, for that matter, anyone who wished to write. It was a fairly unconventional stance, as markets were already thin and competition razor sharp. But the fact remains, it was an L. Ron Hubbard hallmark that he vehemently lobbied on behalf of young authors—regularly supplying instructional articles to trade journals, guest-lecturing to short story classes at George Washington University and Harvard, and even founding his own creative writing competition. It was established in 1940, dubbed the Golden Pen, and guaranteed winners both New York representation and publication in

Argosy.

But it was John W. Campbell Jr.’s

Astounding Science Fiction

that finally proved the most memorable LRH vehicle. While every fan of L. Ron Hubbard’s galactic epics undoubtedly knows the story, it nonetheless bears repeating: By late 1938, the pulp publishing magnate of Street & Smith was determined to revamp

Astounding Science Fiction

for broader readership. In particular, senior editorial director F. Orlin Tremaine called for stories with a stronger

human element.

When acting editor John W. Campbell balked, preferring his spaceship-driven tales, Tremaine enlisted Hubbard. Hubbard, in turn, replied with the genre’s first truly

character-driven

works, wherein heroes are pitted not against bug-eyed monsters but the mystery and majesty of deep space itself—and thus was launched the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

The names alone are enough to quicken the pulse of any science fiction aficionado, including LRH friend and protégé, Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, A. E. van Vogt and Ray Bradbury. Moreover, when coupled with LRH stories of fantasy, we further come to what’s rightly been described as the foundation of every modern tale of horror: L. Ron Hubbard’s immortal

Fear.

It was rightly proclaimed by Stephen King as one of the very few works to genuinely warrant that overworked term “classic”—as in:

“This is a classic tale of creeping, surreal menace and horror. . . . This is one of the really, really good ones.”

L. Ron Hubbard, 1948, among fellow science fiction luminaries at the World Science Fiction Convention in Toronto.

To accommodate the greater body of L. Ron Hubbard fantasies, Street & Smith inaugurated

Unknown

—a classic pulp if there ever was one, and wherein readers were soon thrilling to the likes of

Typewriter in the Sky

and

Slaves of Sleep

of which Frederik Pohl would declare:

“There are bits and pieces from Ron’s work that became part of the language in ways that very few other writers managed.”

And, indeed, at J. W. Campbell Jr.’s insistence, Ron was regularly drawing on themes from the Arabian Nights and so introducing readers to a world of genies, jinn, Aladdin and Sinbad—all of which, of course, continue to float through cultural mythology to this day.

At least as influential in terms of post-apocalypse stories was L. Ron Hubbard’s 1940

Final Blackout.

Generally acclaimed as the finest anti-war novel of the decade and among the ten best works of the genre ever authored—here, too, was a tale that would live on in ways few other writers imagined. Hence, the later Robert Heinlein verdict: “Final Blackout

is as perfect a piece of science fiction as has ever been written.”

Like many another who both lived and wrote American pulp adventure, the war proved a tragic end to Ron’s sojourn in the pulps. He served with distinction in four theaters and was highly decorated for commanding corvettes in the North Pacific. He was also grievously wounded in combat, lost many a close friend and colleague and thus resolved to say farewell to pulp fiction and devote himself to what it had supported these many years—namely, his serious research.