Calligraphy Lesson (11 page)

Read Calligraphy Lesson Online

Authors: Mikhail Shishkin

I found out you'd arrived, my kind Alexei Pavlovich, and rushed off to the vivarium like a woman possessed. I made my way there as if sleepwalking, not myself, which was why I knew I was just about to see you, and suddenly a degenerate old cesspit of a woman approached me at a streetcar stop. She had blue prison tattoos on her arms and even her forehead. She wanted me to buy withered roses from herâlifted, obviously, from the statue of Gogol on the boulevard. “Buy them, girlie,” she wheedled, “for good luck. You'll see, they'll come back to life.” What did I do? I gave her a ruble, which the crone doubtless spent on drink, and immediately I felt that the witch, who stank of prison, had not in fact misled me and I was perfectly happy. Fool that I am, at that minute, at that stop, I would have happily died before the streetcar came. I stood and smiled, not in my right mind, and kept bringing the wilted fragrance to my nostrils and sniffing.

When I arrived, some people were there. You were angry, excited, not yourself. You were shouting that they were all idlers and thieves, that you couldn't leave for a minute, that you knew everything: they were feeding the dogs dog meat, and you knew where the meat allotted for them was going. For a long time you couldn't calm down, you kept snatching walnuts from the bag left over from the monkeys, squeezing three at a time, and the walnuts cracked, shooting off rotten dust. You started in again about how the nuts were dog shit, not nuts. Then someone came to see you and I slipped out because I didn't want to see you like that. They were drowning puppies there. Having nothing to do to keep me busy, I started helping. I'd pour water into the bucket, toss in the pups, and insert a second bucket into the first, also filled with water. I walked past the croaking jugs again for the umpteenth time, between the stands of trays where the white, sharp-clawed blobs bred faster than they could be done in. The dogs would quiet down and then the howling would start up from all the cages. Finally we were alone. I said, “Thanks for the postcard.” You pretended you didn't know what I was talking about. “What postcard?” You held me in your arms and started kissing me. I asked whether you believed that we'd have to answer for all our actions on Judgment Day, and you said, “Let's go before someone else shows up.” You pulled me by the arm, and we crawled into the farthest dog cage, where we put down straw. From directly above us came the barking of crazed canines trying to poke their snouts through the bars and sputtering spit. The sight of bloody cotton wool bothered you. You mumbled, “Zhenya, this can't be good.” I objected, “It's fine.” I reached under your shirt and ran my hands over your back and shoulders, feeling the tiny moles. You startled a few timesâyou kept thinking someone was coming. When they did come from the department to pick up frogs, you had a pleased look on your face, that you'd had time. I said in parting,

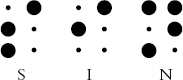

“I'm going to go to your house to pay Vera Lvovna a visit. Say hello for me.” You mumbled, frightened, “Zhenya, I beg of you, don't. Don't come! I can't take it when you're together. It's awful for me.” At home, at dinner, I upset the sauceboat by accident and it all spilled in Mika's lap. She jumped up, waved her arms around, wailed about how I'd ruined her suit on purpose because I always did everything to be mean, because God created me bad and ugly, with a face to stop a clock, and now here I was having my revenge for being an unattractive nobody. I said that Mika was trash because she wanted to marry my father and I was in the way. My father jumped up and slapped my cheek. I said, “I hate you all!” and ran out. I wanted ice cream but I had to make do with snow. Braille isn't nearly as clever as it seems at first glance. Here, this is about me and you:

Zhenya, is that you? Alexei Pavlovich isn't here. How good you've come! I've missed you. This is just how it is, Zhenya. Healthy and pretty, everyone needed me, but I've grown fat and old, and now that I've got this horrible-looking face and missing parts as well, no one gives me the time of day. Don't think I'm hurt. What for? You weren't the one who thought this up and neither was I. We're not the first and we won't be the last. As if I haven't known for five years that one day they'd bury my body. In Yalta people kept asking me, “Why are you so cheerful?” I said, “Just look at that!” A magician there kept pulling a ribbon from his nose. I laughed till I dropped. They looked at me as if I were nuts. But I pitied them all for not laughing. They didn't think it was funny because they

didn't understand something important. But I did.

Verochka Lvovna, tell me about my mama.

Your mama loved candy. Mitya brought her over to meet us, and I put a box of Viennese pralines on the table, a huge one, tub-sizeâand she ate half the box. But that's not the point, Zhenya. The point is that your father loved one woman very much. But she didn't. It happens. She liked it that way. Sheâhow can I put thisâtoyed with him. It flattered her that he suffered so over her. She didn't even marry just anyone but his friend. And then when Mitya married the first girl to come along, he came to his senses. That happens, too, Zhenya. You'll see for yourself.

Verochka Lvovna, why are you lying?

Why indeed? You should always tell the truth. That woman was me, Zhenya. All those years your father and I would meet. And your mama knew about it. I told her all about it. But that namby-pamby, that Little Gray Neck, only whimpered. She asked, “What did I ever do to all of you? What?”

I'm going.

Go. Only listen to what else I have to say. In Yalta I realized why I'm not afraid. Everyone's afraid, but I'm not. Because I loved your father my whole life. I still do. I even wanted to write him about it. But I never did. Or rather, I sent a blank card. It's silly, of course. It never arrived, it got lost somewhere. I say this and I'm lying again because I'm afraid anyway. And also. You and Alexei Pavlovich could at least have waited until I croaked. Or do you think I don't see?

I don't care, Vera Lvovna. I don't believe in God and I smell of apple soap.

My handsome, intelligent, inimitable, delightful, prickly, unlucky Alexei Pavlovich, by the power of imagination invested in me I'll make you who you are because I want to. Your hair is falling out, tufts of it get left in your comb.

Your skin is getting flabby and wrinkled. You're developing a soft, almost feminine belly. After four flights of stairs now you have to catch your breath. You can't see close up, you're afraid of glasses, and you read holding the book at arm's length. Your soiled and chalk-stained jacket hanging on a nail in the classroom by the board automatically spreads its sunlight-reflecting elbows. In the bathroom I scrub your mangled name off the walls. You're ordinary and not that smart. Remember how we started telling our fortunes out of boredom? Your page, my line. We got: “But whoso shall offend one of these little ones which believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea.” You said, “We'll find a rope, but where are we going to get the stone?” I made-believe I was tightening a noose and stuck my tongue out to the side. We burst out laughing. You and I. You're a silly man. After all, I was the one who needed the millstone. You were one of the little ones. And now, like a foolish child, you think someone's angry at you for something, but you don't understand what, and you're lost in speculation as to why people avoid you, you're looking for explanations, seeking out meetings, even writing notes that really don't become you. You're ridiculous and repulsive both. You pulled an underhanded trick, announcing loudly in front of everyone that I should come by your lab after the lecture. I came and became the unwilling heroine of an extremely vulgar scene. I didn't even realize at first that you were asking my forgiveness for the row of our lesser brothers preserved in alcohol with their guts hanging out. You started trying to convince me that you still loved me and that the lack of attention and caresses was simply out of sensible caution because no one should know anything before it was time. “We have to keep a low profile, Zhenya,” you explained. “You have to be patient.” I said all I needed was purity and I left. As it turned out, you didn't understand anything. And now this awful yesterday.

Or maybe, on the contrary, you did understand and that's why it all happened like that. Kind Alexei Pavlovich, do you even remember what happened? You showed up at my father's birthday totally drunk. You wouldn't let anyone get a word in and badgered everyone about what a remarkable father and worthy man he was and poured yourself shot after shot. You pestered Roman to play. The poor boy didn't know where to hide, but you sat next to him, put your arm around him, and wouldn't let him go. You shouted in his ear, “Roman, do you think you're the blind musician? Silly! It's him!” He lifted a forkful of herring toward the ceiling and the sauce dripped down his fingers into his sleeve. “Him! He pounds on us like keys, like this and this!” Mika jumped up. “What are you talking about! You don't even know what you're babbling!” I went to my room and lay down so I wouldn't have to see or hear you. You knocked on the door. I thought it was my father, but it was you. You collapsed to your knees and started kissing my feet and exclaiming that you couldn't go on like this, that you would throw her on the garbage heap, that you had no one and nothing in life but me. I said, “Go away! Get out!” You kept trying to kiss me and I kicked you away. You fell to the floor. They ran into the room. My father dragged you to the front door. You were laughing, trying to break away, and repeating over and over, “Thinking pistil! Thinking pistil!”

There is a famous phenomenon, recovered sight, Evgenia Dmitrievna, described back in the eighteenth century. Someone blind from birth who acquires vision after an operation thinks that the objects he sees are touching his eyes. He can't judge distance and misses when he tries to grab a door knob. They show him a sphere and a cube. But he can only tell what they are by feeling them. Amusing, isn't it?

Here I am writing you one last letter, kind Alexei Pavlovich, which, like the ones before, you will never receive. Any novel, no matter how short, should have an epilogue. Nothing happened, it's just that your Zhenya changed. This different Zhenya came home one fine day and found a tear-stained Mika sitting there. Zhenya asked, “What happened?” Silly question. Zhenya knew full well that Roman had taken the exam and failed. Zhenya stood by the window in her room for a while, watching the little boys in the courtyard taking turns blowing into an empty bottle, and then she went into Roman's room. He was sitting like a statue. Zhenya started reassuring him and said that it didn't matter, it was all silly, because that wasn't what was most important. “What's most important,” Zhenya said, “is that I love you. I'll be your wife, we'll go away from here, and we'll just live.” She started kissing his face, eyelids, and forehead, but he had a fever. They took his temperatureâhe was burning up. They put him to bed. They called the doctor without waiting for my father. Pneumonia. How? Why? Mika and I sat with him that night, together. Roman mumbled something in his fever. Then fell asleep. Zhenya asked, “You don't believe me?” Mika answered, “I do. Roman loves you very much, Zhenechka. And I know that you can make him happy. Only I'm afraid you'll bring him grief.” But Zhenya said, “Whether you believe me or not, I love your son and I'll do everything I can to make things good for him. If only you knew how happy I am right now!” Zhenya sat at his bedside day and night, spoon-fed him, gave him his medicine, sponged off his sweating body, changed his sheets, and took him to the bathroom. She and Mika discussed what kind of wedding they would have. Zhenya wanted it all to be very quietâfirst church and straight home, and there only their closest friends and a simple supper. “Yes yes, Zhenya dear,” Mika agreed. “We'll do everything your way.”

How frightening to wake up without you here, Evgenia Dmitrievna. Here I am holding your hand, and I still can't believe it's true. My beloved, my one and only Zhenya, how well you put it then: we'll get there and just live. You'll be my better half, my spare rib, my God-bestowed wife, and I'll stuff myself on pears.

Before going to the train station, we all sat quietly for a minute. The streetcar outside set the bookcase glass to shaking.

You got all the way downstairs and had to go back.

“The gingerbread! We forgot the gingerbread!”

Cottonwood puffs swept even through the front door.

We arrived at the station early; they'd just brought the train up.

My father flicked a puff off his sweaty face and shielded himself from the sun with a newspaper.

Quickly, get in quickly, it's about to move, any minute now. The train sailed past the Andronikov Monastery, whipped by the oncoming wind.