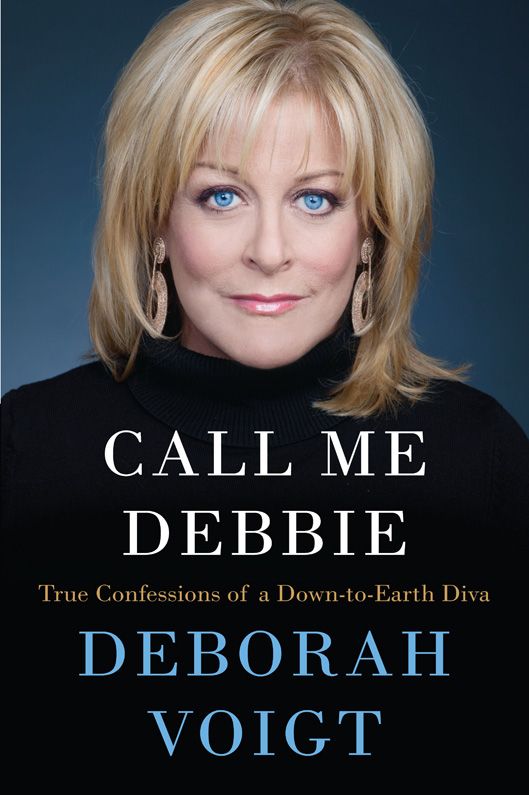

Call Me Debbie: True Confessions of a Down-to-Earth Diva

Read Call Me Debbie: True Confessions of a Down-to-Earth Diva Online

Authors: Deborah Voigt

For Mom, Dad, Rob, and Kevin.

I love you all very much.

THANK YOU TO

my wonderful, funny, loving family: Dad and Lynn, Mom and Don, Rob and Angie, Kevin and Tara, and Marianne.

And to my nieces and nephews that warm this aunt’s heart: Maddie, Kailee, Abby, Nicholas, Graham, Olivia, and Morgan.

And thanks to my cousins Martha, Amy, Peggy, Tony, Brian, and Todd—with whom I’ve shared a lifetime of memories.

A big thank you to Jesslyn Cleary, my assistant through thick and thin and the mistress of “Camp Cleary for Yorkies and Cats.”

Jaime Aita, this book wouldn’t have come together without you. Thank you!

My gratitude to Jane Paul, my mentor and friend—and to Nancy Estes, Ruth Falcon, David Jones, Levering Rothfuss, and Brian Zeger.

To Paul Côte, my first manager, for believing in me all those years ago.

At Columbia Artists Management, many thanks to Ronald Wilford, Elizabeth Crittenden, Alec Treuhaft, Damon Bristo, Tim Fox . . . and to Andrea Anson, for your unconditional support and encouragement. I love you.

To Albert Imperato at 21C Media Group (“Alberto!”), a heartfelt

thanks for your vision and boundless enthusiasm! Same goes to Sean Michael Gross and Michael Lutz.

Natasha Stoynoff, my co-writer; I’ve never bared my soul to anyone as much as I have with you. Thank you for that, and for all those sleepless, marathon, eating-writing sessions.

To Jonathan Burnham at HarperCollins, I’m so grateful for your endless support and patience. Many thanks to Laura Brown and Bob Levine for their valuable contribution to the book.

Thank you to Kim Witherspoon at Inkwell Management.

And to Herbert Breslin, who always loved “a good scandal.”

To my first opera family at the San Francisco Opera—Andrew Meltzer, Christine Bullin, and Sarah Billinghurst.

Thank you to my dear friends: my buddy Jack Doulin, for our morning chats to solve the problems of the world; Victoria Gluth, for endless hours of laughter and amateur psychiatry; Julia Hanish, because I love you, Tyson, Tyce, and Lyles; and Sue Burhop Muszczynski—my secret-voiced, ice-cream caper pal forever.

John Leitch—because you never quite get over your first love.

And finally, thank you to Peter Gelb, Jimmy Levine, Joe Volpe, and the rest of my Metropolitan Opera Family.

8.

Next Stop, the Wiener Staatsoper

10.

Amelia and Ariadne: Luck Be This Lady

11.

Leona, Leonie, Luciano: Breakthroughs and Breaking Up

12.

Dangerous Liaisons and Plácido’s Kiss

14.

Little Black Dress and Sexy Salome

15.

Princes, Rogues, Blackouts, and Bottoms

16.

Fathers, Love, and the Ride of the Valkyries

17.

Fear and Loathing in Liège

Heavenly Voices

WHEN I WAS

fourteen years old, God spoke to me.

I know it will sound unbelievable to most—and if it hadn’t happened to me and someone told me the same thing, I might accuse him or her of hallucinating. But it happened, and I remember it as vividly today, forty years later, as if He’d spoken to me yesterday.

There was no burning bush, no blinding flash of light—but it was a miracle to me nevertheless, even if it was low-key and over in a matter of seconds. Those few mystical moments when I was a teenager forever changed the course of my life.

It happened just a little past dawn on a fall morning in 1974 that began like any other in our suburban home. The rest of my family—my parents, Bob and Joy, and two younger brothers, Rob and Kevin—were asleep, and the usually noisy household was quiet and still. I’d woken up early and was treasuring the silence as if it were a piece of rare and beautiful music. The light was peeking through my bedroom curtains and I snuggled under the blankets, sleepily watching the sun’s first rays slip across the room’s lemon walls.

That’s when I heard Him, a voice that came from everywhere, and out of nowhere. The voice was as clear as day; it was both as

loud as a lion and as soft as a whisper. He said five simple words, but they were powerful enough to put me onto the path I would follow from that moment onward:

You are here to sing.

I know, writing this now, what it must sound like. But I promise you: I sat up in bed and searched the room, wide-eyed. There was no one else there, and for a second I wondered, did I just dream that? No, I was definitely awake. And there was no doubt in my mind who that voice belonged to, I just

knew

. It was otherworldly but so very

real

. I have never been able to describe the timbre, cadence, accent, or inflection of that voice, but if I heard it again I’d know it like I know my own.

I held my breath, waiting to hear if there would be more . . . some additional message, instruction, or revelation . . . anything. But there wasn’t. Five words was it, that’s what I got. I wasn’t given an earth-shaking command to lead my people out of bondage, or to plow up my Illinois cornfield, or to stand on a box in New York’s Times Square and warn the wicked to repent because the end was nigh.

Nope, my message was simple and intensely personal, and, in a way, it was more of an affirmation than a directive.

You are here to sing.

God told me to do what I had always innately sensed I was born to do. And not just demurely, but proudly—with every ounce of passion in my soul and every fiber of my being. It was a dream of mine, even when I couldn’t articulate it.

I never imagined myself becoming a world-famous dramatic soprano who’d share the stages of the biggest opera houses in the world with the most celebrated vocalists of our time. I didn’t yearn to meet presidents, princes, Pavarottis, and Plácidos.

As a child, I only knew I loved to sing.

Had I not heard the voice of God in my bedroom that day, my unarticulated dream may have gotten lost. Because even though I’d

always felt that music was my destiny, the first several years of my life I struggled to hold on to it, to not let that calling be denied.

But as I said, God’s voice that day would firmly plant my feet and my voice on the path that would lead me to fulfill it.

And that dramatic journey begins, appropriately, as all great operas do . . . with music, and a story that stirs the soul.

PICCOLA

My Fair Little Lady

MY FATHER SAYS

I was singing before I was even talking.

His mother, Grandma Voigt, owned a vinyl copy of the

My Fair Lady

movie soundtrack when I was a toddler. And, as family folklore has it, I’d tug at Grandma’s dress and beg her to play the record for me whenever we all visited her in Mount Prospect, a forty-minute drive from our home in Wheeling, Illinois.

Mom and Dad were strict Southern Baptists and, with a few exceptions, any form of non-Christian “secular” music was forbidden in our own ultraconservative home. But my three-year-old mind didn’t comprehend censorship, and to my young ears

My Fair Lady

was as sweet, fun, and innocent as candy, and it made me want to run to the center of the room and sing the songs out loud.

Grandma Voigt was a heavy-set woman—I take after her physically—with a slightly dour disposition. She wasn’t particularly musical and was definitely not the whimsical, gamine, Audrey Hepburn type, so how she ended up with

My Fair Lady

in her record collection, I can’t say. But it was there, and it caught my eye. Every Sunday when we’d visit her, I’d run in the door and rush to Grandma in the kitchen.

“Grandma . . . please, please.

My Lady

?” I’d manage to get out as I tugged at her apron.

“Oh, Debbie. Again?”

She’d wipe her hands and make her way to the long, teak stereo console in the living room, with me following close behind. After she put the record on, she’d give me her apron to use as my costume—which I accessorized with a netted pillbox hat from the front closet and one of Grandma’s shiny brooches, and took my position center stage on the living room floor.

“I’m going to sing now!” I’d announce loudly.

Everyone would stop what they were doing and come in. With the hat falling over my eyes, and with a Cockney accent that would impress the likes of Michael Caine, I belted out at the top of my lungs one of the great refrains in English musical theater:

“Jusst you ’ait, Enry Iggins, jusst you ’ait!”

I think you get the picture.

I was a pint-sized, self-assured, living room diva who performed for the sheer joy of it—not to mention the thrill of having a captive audience.

It took only a few Sunday visits before I had the entire album—all the music and all the lyrics—memorized, an ability I wish stayed with me decades later when my opera career depended on memorizing thick librettos in a variety of languages. But I could do it then with ease, and once I’d conquered

My Fair Lady

, I moved on to a new repertoire,

The Sound of Music

, which came out the following year, and which my mother bought for me (it was one of those secular exceptions—after all, Maria

had

wanted to be a nun). By age four, it had become about more than singing for me—I loved the drama of it all. I’d sashay across the living room in my apron and truly

feel

Maria’s desire to banish all her doubts and fears and find courage and strength inside of her:

“They’ll have to agree, I have confidence in MEEEEEEE!”

My family played along as best they could and clapped, commenting to each other, “Oh, isn’t she cute!” and then, probably, “Don’t worry, she’ll grow out of it.” Because what was most likely

at the forefront of my parents’ baffled minds at the time was: “Who

does

this kid think she is? Where did she come from?”