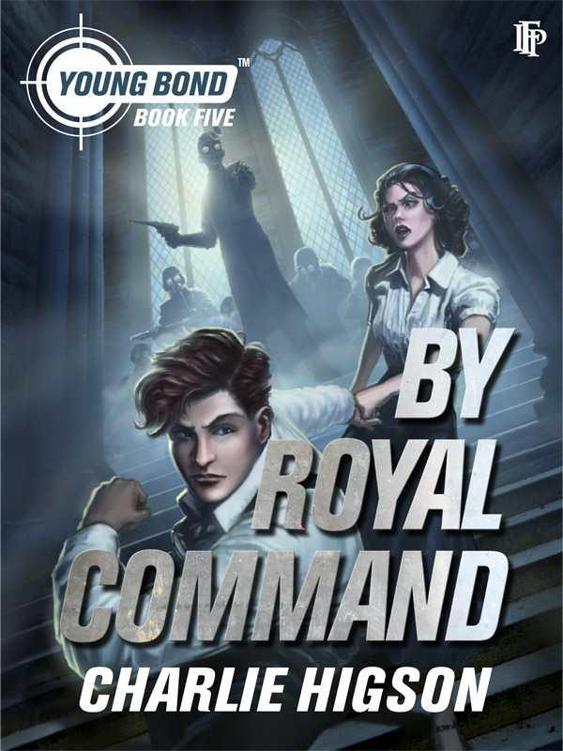

By Royal Command

Authors: Charlie Higson

YOUNG BOND BOOKS BY CHARLIE HIGSON

SILVERFIN

BLOOD FEVER

DOUBLE OR DIE

HURRICANE GOLD

BY ROYAL COMMAND

DANGER SOCIETY: YOUNG BOND DOSSIER

SILVERFIN: THE GRAPHIC NOVEL

BY ROYAL COMMAND

CHARLIE HIGSON

Ian Fleming Publications

IAN FLEMING PUBLICATIONS

E-book published by Ian Fleming Publications

Physical books available from:

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Disney-Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group, 114 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011-5690

Ian Fleming Publications Ltd, Registered Offices: 10-11 Lower John Street London

First published by the Penguin Group 2008

Copyright © Ian Fleming Publications, 2008

All rights reserved

Young Bond and By Royal Command are trademarks of Danjaq, LLC, used under licence by Ian Fleming Publications Ltd

The moral right of the copyright holder has been asserted

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-1-906772-65-9

For Vicky

In memory of Kate Jones

My thanks to Franz Hink of the Kitzbühel ski school for teaching me how to ski and showing me the mountains.

Contents

2

It is Only When We Are Close to Death That We Feel Fully Alive

6

There is More Than One Way to Come Down a Mountain

11

Consorting With a Common Maid

17

Science is Not a Boring Subject

19

One Move and I’ll Tear Your Throat Out

Colonel Irena Sedova of the OGPU hated tractors. She would be happy if she never saw a tractor again as long as she lived. She had built tractors, she had driven tractors, she had unveiled statues of tractors, she had made countless speeches in foreign towns singing the praises of tractors… Russian tractors, communist tractors, the greatest tractors in the world!

She had endured the Great War, the revolution and the civil war that followed it. She had lived through the terrible famine of 1921, where, in the frozen, impoverished countryside, people had been reduced to eating anything they could – weeds, grass, rats, leather shoes, even each other. She had survived the purges of the last ten years, and three assassination attempts, but she would gladly have lived through it all again rather than spend another minute with one of these infernal, god-forsaken machines.

But here she was, on a cold March morning, watching a parade of them drive around a square in an ugly industrial quarter of Lisbon for the benefit of a group of bored Portuguese businessmen and local officials.

The twenty tractors, from the Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant, were of varying designs but they shared several things in common. They were noisy, they were dirty and they were ugly.

Colonel Sedova had grown up on a farm in the Ukraine. Back then, at the end of the last century, there had been no tractors. Farm work was done by horse and ox and peasant. It was only after the revolution that they had started to appear in Russia, or the Soviet Union as it was now called. They were the symbol of the new Russia, of a fabulous modern world. They would revolutionise agriculture just as Lenin had revolutionised everything else. When the new tractor arrived in a village there would be celebrations. It would drive slowly into town at the head of a long procession, followed by men and women and children waving flags and singing patriotic songs.

Having fought bravely, and fiercely, in both the war and the revolution, Colonel Sedova had joined the Ministry of Propaganda and one of her first jobs had been to make a series of films in which the hero was a Russian tractor. Later on she had joined the Obedinennoe Gosudarstvennoe Politicheskoe Upravlenie, the Russian secret police. Her job now was to run spies and secret agents throughout Europe, with the aim of undermining foreign governments and eliminating anyone who might be working to harm the new communist regime.

At last

, she had thought,

I can get away from tractors

.

It wasn’t to be, however. A group of Russian secret agents would attract a great deal of attention in a foreign country unless they pretended to be something else. All spies needed a cover. So Colonel Sedova and her team travelled the world pretending to be part of a Soviet trade delegation selling Russian tractors.

She sighed. The life of a spy was not as romantic as it was presented in popular novels. Most of her time was spent being bored to death.

But this morning she had a mission.

She looked around. Nobody would notice if she left now. The Portuguese would want to talk to the engineers about tedious things like engine sizes and power output and haulage capabilities. She would not be missed.

She muttered something to her secretary, Alexa, stepped backwards into the shadow of a warehouse, then slipped away down an alley to where her car was waiting. It was a brand-new black unmarked Citroën Traction Avant. She loved this car. The French may be enemies of the mother country, but they certainly knew how to build automobiles. Her driver, Anatoly, opened the door for her and she climbed in and settled back in her seat, breathing in the scents of wood and leather. The scents of luxury.

‘To the Alfama district,’ she grunted and Anatoly set off, driving quickly and efficiently through the streets of Lisbon. He took a few random turns and switchbacks to make sure that they were not being followed, and, once he was sure they were clean, he pressed on towards the old part of town.

Sedova, known by most as Babushka, the grandmother, didn’t pay any attention to the passing scenery. She was lost in her thoughts. Concentrating on the mission ahead.

What exactly was Ferreira up to?

A small group of spies working together was called a cell. The members of a cell would know the identities only of the other members. This meant that if one was caught and interrogated he would not be able to give away any information about the rest of the spy network. Only the leader of the cell would know the identity of the next person up the chain, and sometimes the identities of other cell leaders, but, once again, if they were ever found out they would be able to betray only a handful of other spies. A cell structure was a secure structure, but if a cell leader turned bad it could cause problems.

Martinho Ferreira ran the most important communist spy cell in Lisbon from a bookshop that specialised in works on art, music and architecture. Ferreira reported directly to Franco Fortuna, the Soviet officer for southern Europe, who was based in Rome, and Fortuna reported to Moscow.

There was a problem, though, and Colonel Sedova had been forced to break cover and come down personally to deal with this business. A cipher expert at the OGPU headquarters in Moscow had noticed a change in Ferreira’s reports, subtle differences that would perhaps not have been noticeable to most people, but to the trained and deeply suspicious eyes of the expert they stood out glaringly. A careful search in the files revealed that the changes went back several months. What had happened? Why was there this change? Had Ferreira’s cell been infiltrated? Had he been turned by some foreign power? The Germans, perhaps, or the British?

Babushka would find out. She would find out and she would deal with it.

They came to the walls of the Castelo, swerved around a rattling wooden tram, and started to wind their way down through the labyrinth of narrow cobbled streets and small squares of the medieval Alfama quarter towards the wide grey expanse of the Rio Tejo.

The bookshop was on the northern edge of the district, near the flea market in the Campo de Santa Clara. Anatoly stopped the car by a row of dirty orange houses, applied the handbrake but left the engine running.

‘Leave the car here and go to the rear of the building,’ said Babushka, climbing out of the Citroën. ‘Watch for anyone going in or out. Follow them if necessary. I will go in the front.’

Anatoly nodded and cut the engine.

Olivia Alves looked up as the bell above the door rattled and chimed. She peered with some curiosity at the woman who came in. She didn’t look like the usual customers they got in the shop. In the three weeks Olivia had been working here the trickle of customers had for the most part been professors and students from the university or bearded bohemian types. Neither did the woman look like any tourist she had ever seen, though she was certainly not Portuguese. She was from a northern country, Germany perhaps. She was short and stocky and dressed all in grey. A skirt and jacket that were too tight for her and strained at the seams. Grey woollen stockings. Grey lace-up boots. Her hair was grey, too, and her skin. She had a flat peasant’s face and small watchful eyes. She made a brief show of looking at the books on the shelves, and then marched over to the table where Olivia sat reading a book on Tintoretto.

‘Is Senhor Ferreira in?’ the woman asked in clumsy Portuguese.

Olivia nodded towards the rear of the shop. The woman grunted and walked off. Her back was wide and solid as a lump of rock.

Babushka had to duck her head to get under the low arch that led into a warren of book-lined corridors and tiny rooms that lay behind the main shop. She plodded steadily between the shelves until she eventually spotted a bearded man sitting in an alcove, studying some papers under a desk lamp and eating a sandwich that smelt of garlic.

He looked up as she approached and slipped a pair of glasses down from his forehead on to his nose. He had a long droopy face that had a melancholy look about it.

Sedova studied him for a moment then spoke in clumsy Portuguese. ‘Are you Martinho Ferreira?’

‘But of course,’ the man replied.

Sedova now slipped into her native Russian. ‘Tell the girl to go for her lunch,’ she said. ‘And close the shop.’

The man smiled vaguely, pretending not to understand.

‘I am Sedova.’

The man paled, dropped his sandwich and jumped up from his ancient, rickety chair. He hurried off and Sedova heard low voices, then the opening and closing of the street door.

Sedova walked over to the desk and cast a quick, professional glance over it.

Something caught her eye: a scrap of paper with a name on it. A name from her past. She frowned and quickly slipped it into her jacket pocket as she heard the man returning.

He came through, smiling and wiping his palms on his jacket.

‘Babushka,’ he said, extending a hand, and went on in fluent Russian, ‘I am honoured to meet you. I have heard so much about you.’

Sedova did not shake his hand.

‘We need to talk,’ she said.

The man fussed about, clearing a space for the colonel to sit. They were in a cave of books and every surface, including the floor, was piled high with dusty volumes.

Sedova remained standing and the man returned to his chair.

‘Is there a problem?’ he said.

Sedova did not reply. She was quietly studying the man. She had never met him before but she had seen his records and the photographs kept on file at OGPU headquarters.

This man looked similar, but he was clearly not Ferreira. He was a good two inches too short and his nose was the wrong shape.

‘You are not Martinho Ferreira,’ she said.

The man shrugged. ‘I am not,’ he said. ‘Martinho is not here at the present.’

‘Then why did you say you were him?’

‘You cannot be too careful.’ The man laughed and fished a bottle of vodka from his desk.

‘Would you care for a drink?’ he said.

‘I do not drink,’ said Sedova.

‘If you will allow me.’ The man poured himself a hefty measure, the bottle rattling against the rim of the glass.

‘You know who I am?’ said Sedova.

‘But of course. You are Colonel Sedova. Everyone in the network knows who you are. You are famous.’

‘What is your name?’

‘My name? Cristo Oracabessa. I work with Martinho.’ He returned the bottle to his desk drawer.

‘When will Martinho return?’ said Sedova. ‘I would dearly like to speak with him.’

‘Alas. He will not be returning,’ said Cristo, raising a pistol above the edge of the desk as he did so. ‘You are too late.’

Sedova recognised the gun – it was a Soviet design, a Tokarev TT-33 semi-automatic. A very efficient weapon.

She remained calm. She had no doubt that the man would use the gun. He knew her reputation. He would have heard all the stories. They called her the grandmother, but there was irony in it. She was a hardened killer. She would do anything to survive. Along with many other people she had eaten human flesh during the great famine. It was good to keep the story alive. A fearsome reputation was a necessary thing, but it all seemed so long ago now. She couldn’t remember what the flesh had tasted like. As far as she was concerned it was the same as all the other boiled grey meat she’d had to endure over the years.

Yes. This man would know the stories.

He would know that there would be no second chances.

There was a film of sweat along his upper lip.

‘It seems you thought I might be coming?’ said Sedova. ‘Me or someone like me.’

‘I hope you are not expecting me to explain myself before I kill you,’ said the man.

‘I do not expect anything,’ said Sedova. ‘The Spanish have a saying:

O que ser.

.’

‘What will be, will be,’ said the man and he pulled the trigger three times, aiming at the largest part of his target, Sedova’s torso. Each bullet found its mark and the combined force of the three of them was enough to knock the woman off her feet. She fell into the bookshelves behind her and collapsed to the floor beneath a cascade of books.

So Cristo, if that was his name, was not stupid. One bullet might not have been enough, three was plenty, and any more would have been a waste.

The man let out a deep sigh, his lips fluttering, and started to walk cautiously towards the colonel.

You did not live to be fifty in the OGPU without learning a trick or two. Sedova had learnt to be cunning and wary and distrustful. She had been shot once before, during the civil war, and still had a nasty scar in her side where a comrade had clumsily removed the bullet. It had been enough to teach her that she never wanted to be shot again. Which was why she had taken to wearing a steel-enforced corset with a leather backing. With thick layers of fat and solid muscle underneath, it would take more than a bullet from a TT-33 to reach any of her vital organs.

When she landed she made sure that she kept her arms bent and her hands drawn back, ready to strike. Now she lay perfectly still, holding her breath in and her eyes open. She was careful not to allow them even a tiny flicker but followed the man’s movements with her peripheral vision. She would wait. She was used to waiting.