Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (6 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Every time Josephine concludes a conversation with Mukul, her counterpart in India, she sends an email summarizing the contents of her call. When Mukul does not do the same, Josephine finds it annoying. She reminds him of company policy, compelling him to comply.

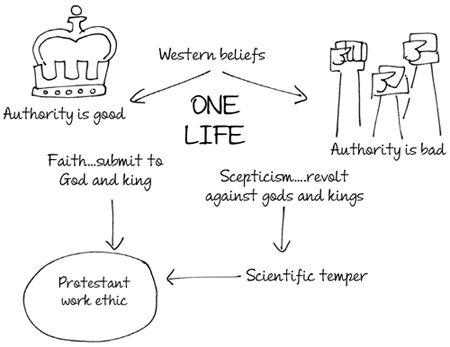

Despite many shared beliefs, Christians persecuted the Jewish people across Europe and fought Muslims over four centuries, from the tenth century onwards, in what came to be known as the Crusades. Within Christianity itself there were many schisms, with the Churches of Rome in the West and Byzantium in the East vying for supremacy. Every side believed in one God, one life, one way of living life, but they differed violently over who had the patent over the right way.

The end of the Crusades saw the start of the scientific revolution in Europe, inspired by the rediscovery of Greek beliefs. Truth imposed by authority was rejected; truth churned by reason was sought. The scientist was the Greek hero on a lone quest, those who opposed him were the Olympian gods. The scientific spirit inspired discoveries, inventions, and industrialization. It laid the foundation for colonization and imperialism.

Scientists did not find any rational explanation for the existence of inequality and social unfairness. They blamed it on irrational ideas like God whose existence could not be measured or proved. With the scientific revolution, society no longer needed anchors of faith. Knowledge mattered, not belief. Everything had to be explained in tangible material terms. The goal had to be here and now, not in the hereafter. The goal had to be measurable, even in matters related to society. Thus rose economic theories that saw all the problems of society as a consequence of faulty wealth generation (Capitalism) and faulty wealth distribution (Communism). Both promised a heaven, one through development and the other through revolution.

But not everyone was willing to give up religion altogether. Those who were firm in their belief in God attributed social wrongs to temporal religious authority, clergymen in particular, for legitimizing the feudal order of kings. The Church became the new Olympus to be defied. Scientific evidence was demanded for their dogmas and their claim of divine rights. Failure to present it led to the Protestant Revolution, spearheaded by the newly emerging class of merchants, industrialists, and bankers. They valued autonomy over all else, and sought equal if not higher status than landed gentry, who for centuries had been inheriting both fortune and status, without any personal effort.

The Protestant Revolution was marked by great violence, especially the Thirty Years' War that devastated Europe in the seventeenth century. It marked the end of feudal orders and the rise of nation states. Many Protestants made the newly discovered continent of America their home: this was the New World, the Promised Land. Here there were no kings, no clergy. Everyone was equal; everyone had a right to personal faith in the privacy of their homes; work was worship, and wealth born of effort was seen as God's reward for the righteous. This was the Protestant work ethic, a unique combination of biblical value for compliance and Greek disdain for authority.

Much of the political system of the United States came to be modelled along the lines of the pre-Christian Roman republic, complete with a senate in times of peace and a dictator in times of war. The American system ensured the victory of democracy, secularism, and most importantly Capitalism. It is from this context that management science arose.

Not surprisingly, the recommendations of management science resonate with not just a scientific obsession with evidence and quantification but also biblical and Greek beliefs. The vision statement is the Promised Land; the contract is the Covenant; systems and processes are the Commandments; the 'fifth' level leader who is professionally ambitious and personally humble is the prophet; the invisible shareholder is the de-facto God. The innovator is the Greek hero, standing proud atop Maslow's hierarchy of needs, self-actualized, and secure in Elysium. Every advocate of any idea from greed to good governance is convinced they know the truth, hence the moral burden to evangelize and sell.

All this makes management science a secular expression of beliefs that have always existed in the West.

Kshitij always smiles when his partner from a very reputed global strategic firm meets him in the club. Kshitij reveals, "He is always selling something or the other. Two years ago he told me about the importance of a matrix structure where no one is too powerful. Now he is selling the idea of creating a special talent pool of potential gamechangers. Then he kept talking about getting people aligned to a single goal. Now he talks about flexibility. They can never make up their mind. Each time they are convinced that whatever they are selling is the best idea, one that will change the world forever. They claim to be global, but are so evangelical. But we have to indulge them; their way of thinking dominates the world. It comforts investors."

Chinese Beliefs

The West, with its preference for the historical, would like to view current-day China as an outcome of its recent Communist past. But the mythological lens reveals that China functions today just as it did in the times of the Xia and Shang dynasties, over five thousand years ago, with great faith in central authority to take away disorder and bring in order.

A pragmatic culture, the Chinese have never invested too much energy in the religious or the mythic. What distinguishes Chinese thought from Western thought is the value placed on nature. In the West, nature is chaos that needs to be controlled. In China, nature is always in harmony; chaos is social disorganization where barbarians thrive.

The mythologies of China are highly functional and often take the form of parables, travelogues, war stories and ballads. The word commonly used for God is Shangdi, meaning one who is above the ruler of earth. The word for heaven is Tian. But God in Chinese thought is not the God of biblical thought. Rather than being theistic (faith in a divine being who intervenes in the affairs of men in moral and ethical matters), the Chinese school of thought is deistic (faith in an impersonal greater force within whose framework humanity has to function). The words Shangdi and Tian are often used synonymously, representing morality, virtue, order and harmony. There are gods in heaven and earth, overseen by the Jade Emperor, who has his own celestial bureaucracy. They are invoked during divination and during fortune telling to improve life on earth. More importantly, they represent perfection. So, perfection does not need to be discovered; it simply needs to be emulated on earth. The responsibility to make this happen rests with the Emperor of the Middle Kingdom. This is called the Mandate of Heaven. It explains the preference for a top-down authoritarian approach to order that has always shaped Chinese civilization. The Chinese respect ancestors greatly. They are believed to be watching over the living; the least they expect is not to be shamed.

In the Axis Age (roughly 500 BCE) when classical Greek philosophers were drawing attention to the rational way in the West, and the way of the Buddha was challenging ritualism in Vedic India, China saw the consolidation of two mythic roots: the more sensory, individualistic, natural way of Tao proposed by Laozi and the more sensible social way proposed by Confucius. Taoism became more popular in rural areas amongst peasants while Confucianism appealed more to the elite in urban centres. These two schools shaped China for over a thousand years, before a third school of thought emerged. This was Buddhism, which came from India via the trade routes of Central Asia in the early centuries of the Common Era.

- Taoism is about harmonizing the body and mind by balancing nature's two forces, the phoenix and the dragon, the feminine Yin and the masculine Yang. It speaks of diet, exercise, invocations and chants, which bring about longevity, health and harmony. It is highly personal and speaks of the way (Tao) through riddles and verses, valuing experience over instruction, flow of energy over rigid structure, and control without domination. It speaks of various gods who wander between heaven and earth, who can be appeased to attract health and fortune. The division of the pure soul and impure flesh seen in Western traditions does not exist. There is talk of immortality, but not rebirth as in Indian traditions.

- Confucianism values relationships over all else: especially between parent and child, man and woman, senior and junior, and finally the ruler and the subjects. Great value is placed on virtue, ethics, benevolence and nobility. This is established more by ritual and protocol, rather than by rules, as in the West, or by emotions, as in India. Thus, the Chinese (and Japanese) obsession with hierarchy, how the visiting card should be given and where it should be placed, and what colours should be worn at office, and what items can or cannot be given as gifts. The gwanji system of business relationships that this gives rise to is very unlike the caste system, as it is not based on birth, or bloodline, or even geography, but can be cultivated over time based on capability and connections.

- Buddhism met fierce resistance as it is highly speculative and monastic. It denied society, which followers of Confucianism celebrated. It denied the body, which followers of Taoism valued. It spoke of rebirth, which made no pragmatic sense. It was seen as foreign until it adapted to the Chinese context. The Buddhism that thrived in China leaned more towards the altruistic Mahayana school than the older, more introspective Theravada line that spread to Myanmar and Sri Lanka. In keeping with Confucian ideals, greater value was given to petitioning the compassionate Bodhisattva, visualized as the gentle and gracious lady Kwan-yin, who is more interested in alleviating rather than understanding human suffering. In line with the Taoist way, the minimalist Zen Buddhism also emerged, but it was less about health and longevity and more about outgrowing self-centredness to genuinely help others.

The famous Chinese novel,

Journey to the West,

describes the tale of a Chinese monk travelling to India assisted by a pig (the Chinese symbol of fertility) and a monkey (inspired by Hanuman?) and indicates the gradual assimilation of Buddhism into the Chinese way of life.