Burma/Myanmar: What Everyone Needs to Know (3 page)

Read Burma/Myanmar: What Everyone Needs to Know Online

Authors: David I. Steinberg

The kyat (K.), on independence in 1948, was equal to the Indian rupee. It is divided into 100 pya, but inflation has eliminated their use. The official exchange rate is K.5.8–6.8 to the U.S. dollar (based on an International Monetary Fund basket of currencies). This is used only in certain government calculations. There are also other exchange rates for foreign trade, official conversions, and so on. The unofficial rate varies, but in the summer of 2009 was about K.1,000 = US$1. There are also foreign exchange certificates supposedly at a par to the U.S. dollar but slightly discounted at about K.950 in April 2009.

Myanmar is divided into seven divisions (provinces, but called regions in the 2008 constitution) and seven states (also provinces), the former indicating essentially Burman ethnic areas, and the latter minority regions. There are a multitude of ethnic and linguistic groups, subdivided into various dialects. The Burmese call them “races,” which is a translation of the Burmese

lu myo

(lit. “people type”), which can mean ethnicity, people, race, or nationality. The government maintains there are 135 such groups.

Under the proposed constitution, in 2010, and in addition to the seven states and seven regions, there will also be six ethnic

enclaves that will have some modest degree of self-governance. The “self-administered [ethnic] zones” are Naga, Danu, PaO, Palaung, Kokang, and a “self-administered division” for the Wa. The boundaries are not ethnically delineated. There are 65,148 villages in 13,742 village groups, 63 districts, and 324 townships.

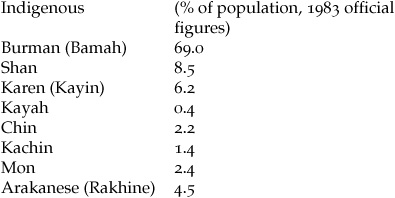

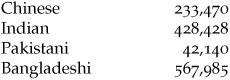

These figures are subject to dispute. There are a variety of other important minorities, such as the Naga, Wa, Palaung, and so on, who are not separately calculated in the 1983 census. The Rohingya in the Rakhine State near the Bangladesh border are considered stateless. The following table indicates the foreign ethnic groups resident in Burma/Myanmar (from the 1983 census).

Estimated in 2008, Burma has a population of 53 million. Other figures range from 47 to 58 million. In preparation for the referendum on the constitution in 2008, the official figure was 57,504,368. But this is likely to be spurious specificity.

Rangoon population is estimated to be 5 million, Mandalay 1.3 million, and Moulmein, 600,000.

The gross domestic product per capita in 2006 (at the free market rate of exchange) was variously calculated at US$210 to US$300, at purchasing power parity in 2010 about US$426.

Myanmar’s official exports in 2007/2008 (the Burmese fiscal year begins April 1) were US$6.043 billion, of which natural gas was US$2.590 billion, agricultural products US$1.140 billion, gems and jewelry US$647 million, forest products US$578 million, and fisheries US$366 million. Due to extensive smuggling, both import and export figures are likely to be grossly underestimated. National debt was US$7.176 billion (December 2008). Real GDP growth rates were 0.9 percent in 2008 and 0.3 percent anticipated for 2009. The nominal GDP was US$26,488 million in 2009.

Buddhist monasteries in 2008 number over 56,839, monks over eighteen years of age over 246,000, novices over 300,000, and nuns over 43,000.

In 1988, there were purportedly 66,000 insurgent troops.

“Data are very unreliable. Facts are negotiated more than they are observed in Myanmar.” There are no notes in this volume, as specified by the publisher, but this does not indicate a lack of sources. Although the interpretation and conclusions are those of the author alone, the statistical bases for these opinions may be found in a variety of official and unofficial documents. Statistics, however, are often imprecise or manipulated, caused by internal political considerations or insufficient data, and biased externally by a lack of access to materials. Some opinions stated are from residents of Myanmar, who for obvious

reasons must remain anonymous. For additional material, the reader is referred to the Suggested Reading section.

Burma/Myanmar is the largest of the mainland Southeast Asian states (261,970 square miles, 678,500 square kilometers), about the size of Texas. It is the fortieth largest country in the world. Burma/Myanmar is some 1,275 miles long from its northernmost mountainous region near the Tibetan border to the mangrove swamps on the Bay of Bengal at the Thailand border. From its eastern extreme on the Mekong River bordering Laos to the Bangladesh border on the west, it is some 582 miles wide. It has a littoral on the Bay of Bengal of 1,199 miles. Its highest point is a mountain on the China/Tibetan border (19,295 feet). The border with China alone is 1,358 miles, that with Thailand 1,314 miles, India 857 miles, Bangladesh 152 miles, and Laos 125 miles.

If we think of Burma/Myanmar in ethnic terms, around a central geographic core of lowlands inhabited by the majority Burmans, two-thirds of the population, there is a horseshoe of highland areas inhabited by minority peoples who also live across the frontiers in adjacent states. Starting from the southwest, they are the Muslim Rohingya, the Chin, the Naga, the Kachin, the Wa, the Shan, the PaO, the Kayah, the Karen, and the Mon. There are many more groups. The government claims 135 such entities (the Chin alone are said to have 53 groups), but this is a calculation from the 1931 colonial census that counted ethnicity, language, and dialect in an obscure methodology.

Major rivers flow north to south, the most important of which is the Irrawaddy, navigable from Bhamo, about sixty miles from the China border to the Bay of Bengal. The Chindwin River feeds into the Irrawaddy from the west in central Burma and is also navigable. The Sittang River is of smaller size; the majestic Salween River’s headwaters are in southwest China in the Tibetan plateau. It bifurcates the Shan

State, and empties into the Gulf of Martaban, part of the Bay of Bengal.

I assume that readers will not read this book through as they would a novel (although the charge of fiction in the absence of reliable data is an interesting one, and happy endings are lacking). There is considerable planned repetition of information so that readers who look up a question of interest in the table of contents do not need to scour a set of other related questions in order to receive a reasonable answer.

They know the foreign visitor is discreet and is not a reporter looking for sensational comments. He will not quote, and thus endanger, anyone. In Rangoon (Yangon) or even up-country, one must be cautious in talking with people about the current situation in Myanmar. Often in such conversations there seems to be a type of quiet, almost silent, understanding that there will not be requests for anything mundane or anything explicit. Yet one senses a longing for an optimistic future, some kind words indicating that the outside world understands and has not forgotten those innocents caught in the Myanmar miasma. Often, a tentative question is asked: can you give us some hope? Not a solution, not manna rained down, but the simple feeling that things may get better … sometime.

It is sad and also embarrassing to admit honestly that one cannot offer an early way out of the present set of crises. Humanitarian assistance should be provided for the neediest, of course, but this is not a solution. It is only an amelioration, no matter how badly it is needed for those endangered. Advocating that people rise up to the barricades—asking others to expose themselves and their families to harm when, as a foreigner, one is physically removed—is morally unacceptable and in any event foreign involvement would undermine the legitimacy of the cause in which they believe. On the other hand, exhorting isolation exacerbates the very issues one

would like to overcome, and plunging in with support to the regime retards positive change. Even external analyses have had little immediate effect.

That change will come—is coming—seems evident. In less than a year a “Saffron Revolution” (that was neither saffron in color nor a revolution in politics, but so named analogous to other “colored” demonstrations elsewhere) started and was destroyed; a new but flawed constitution was approved in a pseudo-referendum; the greatest natural disaster ever to befall Burma/Myanmar in historic times occurred; and elections are in the offing. This is certainly not progress, but the forces that will be unleashed, including an invigorated civil society, and their effects will move Myanmar, perhaps in unknown ways, and will affect international relations and attitudes.

But whatever progress is made will be by the Burmese peoples themselves in a manner that is acceptable to them, rather than externally imposed. Foreign formulae, even when they may be well intentioned, are largely extraneous. The unique history of Burma/Myanmar, as outlined in this short volume, calls for unique solutions to rather common international problems that many states share, although those in Myanmar are exacerbated. The facts connected with these crises may be soundly articulated abroad, their historical antecedents evident, but solutions will come from within. Years ago, when something was to be done, the cry was, “Do it

bama-lo

,” in the Burmese manner. The government surely would approve of the sentiment much as they would disapprove of the language, decreeing that what was needed must be done “

Myanmar-lo

,” in the Myanmar manner.

Either way, the outside world can sympathize with the plight of the peoples, can provide some emergency humanitarian assistance, can attempt to convince the authorities of the need for progress and humanity, can reiterate and call for adherence to the kingly governmental virtues of the Buddhist canon, and can invoke the Buddhist concept that change is inevitable.

Within that construct, the external world can educate itself to the complexities that are Burma/Myanmar and some possible avenues for alleviating its problems. So when the time comes, as it surely will, outside communities will be able to appreciate the nuanced issues and step forward with the sensitivity necessary to help intelligently, in contrast to many less effective responses of the past. We on the periphery should minimally follow the physicians’ code: do no harm.

This volume is a small effort in that direction.

BURMA/MYANMAR

WHAT EVERYONE NEEDS TO KNOW

THE CRISES THAT ARE BURMA/MYANMAR

Burma/Myanmar is, after North Korea, probably the most obscure and obscured state in the contemporary world. It seems to appear on the world stage only in moments of crisis, but its problems are both enduring and tragic. Its future influence will be significant. Its strategic importance, natural resources, size, location, potential, and even its attempts to encourage tourism and foreign investment should have made it better known, but Westerners are only vaguely aware of it. It is on many powers’ policy agendas, yet never in the top tier. It has been called in the United States a “boutique issue.” Concerns over its autocratic military government and the plight of its peoples are widespread, yet there is no international consensus on how to approach and relate to Myanmar. Indeed, there are stark differences. This modest volume attempts to explain the reasons the world should be interested in that state and the many, often subtle factors that have positively or negatively affected both its internal affairs and foreign responses to them. Rudyard Kipling presciently wrote, “This is Burma, and it will be quite unlike any land you know about.”

Burma is an anomaly. There are probably more people today outside that state who know the name of one famous Burmese

than who know the new name of the country in which she lives, even though they may not be able to pronounce either correctly. The continuing house arrest of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, has generated both concern and admiration for her throughout the world. For many abroad, she has come to personify the Burmese crisis: its need, so long delayed, for human rights, democracy, and economic development. Concern for her is compounded by perceptions of her vulnerability and protection for her safety.