Broadchurch

Authors: Erin Kelly,Chris Chibnall

Erin Kelly’s first novel

The Poison Tree

was a bestselling Richard & Judy Book Club selection in 2011 and was adapted for the screen as a major ITV drama in 2012. Erin also works as a freelance journalist, writing for newspapers including

The Sunday Times

,

the Sunday Telegraph

and the

Daily Mail

as well as magazines including

Red

,

Psychologies

,

Marie Claire

and

Elle

. She lives in London with her family.

The Poison Tree

The Sick Rose

The Burning Air

The Ties That Bind

COPYRIGHT

Published by Sphere

978-0-7515-5559-2

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © Chris Chibnall 2014

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Based on the television series ‘Broadchurch’ produced by Kudos and Imaginary Friends Productions.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

SPHERE

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

Broadchurch

Table of Contents

There is a condition worse than blindness, and that is seeing something that isn’t there.

THOMAS

HARDY

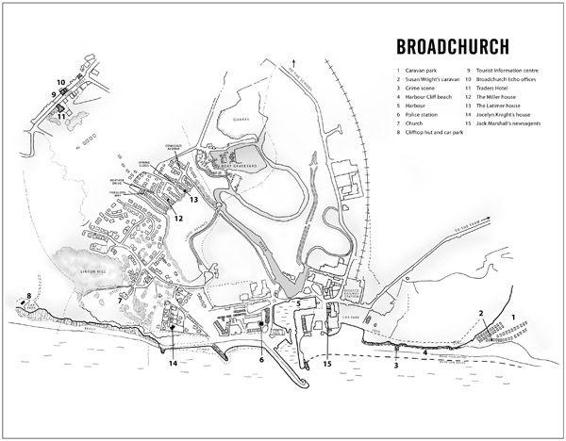

One road in, one road out. Broadchurch isn’t on the way to anywhere and you don’t go there by accident.

This sleepy coastal town is preparing to wake up for the summer season, but tonight nothing stirs. It is the crisp, clean night that follows a hot, cloudless day. There is a full moon and stars prickle the sky. Waves drag and crash as the petrol-black sea retreats from the beach. The Jurassic cliffs above glow amber, as though still radiating the heat they absorbed during the day.

On the deserted High Street, few shops bother to keep their lights on overnight. A single page of newsprint – yesterday’s news – tumbles noiselessly down the middle of the road. The

Broadchurch Echo

headquarters and the neighbouring tourist office are in shadow, save for the occasional blink of computer equipment on standby.

In the harbour, boats bob and masts clank in the shadows. Overlooking the cobbles and jetties is the modern police station, its round steel keep clad in blond wood. The blue light outside flickers. Even a sleepy town keeps one eye open at night.

The church on the hill is unlit, the rich jewel colours of its stained-glass windows dulled to a uniform satin black. A weathered poster reading

LOVE

THY

NEIGHBOUR

AS

THYSELF

flaps uselessly from the parish noticeboard.

At the other end of town, the Latimer house is in darkness too. Their semi in Spring Close is like all the others on their estate; their estate is like all the others in the country. Moonlight shines through eleven-year-old Danny’s half-open bedroom window, silvering posters, toys and an empty single bed. The side gate is ajar and the latch bangs slightly in the breeze but the sound does not wake his parents Beth and Mark, who sleep back-to-back underneath a BHS duvet. A bedside clock ticks off the seconds. It is 3.16 in the morning.

Danny is a mile and a half away, shivering in his thin grey T-shirt and black jeans. He is sixty feet above the sea, his toes inches from the cliff edge. A sharp gust whips his hair into little needles that jab at his face. Tears chase blood down his cheeks and the wind rips the cries from his lips. Below him is a sheer drop. He is afraid to look down. He is even more afraid to look back.

The sea breeze snakes through the town until it reaches his home and bangs the latch more insistently. Beth and Mark sleep on. The bedside clock jumps to 3.19, then stops.

On the clifftop, Danny closes his eyes.

One road in, one road out. Tonight, no engine fills the silence and the sweep of the coast road is unbroken by headlights. Nobody comes in to Broadchurch and nobody leaves.

Beth Latimer jerks upright in bed. This is the way she used to wake up when her children were babies, some sixth sense flooding her veins with adrenalin and shaking her wide awake seconds before they started to cry. But her children aren’t babies any more, and no one is crying. She has overslept, that’s all. The space beside her is empty and the bedside clock is dead. She gropes for her watch. It’s gone eight.

The others are awake: she can hear them downstairs. She’s in and out of the shower in under a minute. A glance out of the window tells her it’s going to be another hot one, and she pulls on a red sundress. You’re not supposed to wear red with auburn hair, but she loves this dress; it’s cool, comfortable and flattering too, showing off the flat (for now, at least) belly that is one of the few benefits of having kids so young. It still smells vaguely of last year’s sun lotion.

Passing Danny’s bedroom, she notices with a shock that he has made his bed. The Manchester City duvet cover that his dad hates so much – he has taken Danny’s sudden defection from Bournemouth FC as a terrible betrayal – is smooth and straight. She can hardly believe it; eleven years of nagging have finally paid off. She wonders fondly what he wants. Probably that smartphone that his paper-round wages won’t quite stretch to.

She can tell by the trail of destruction in the kitchen that Mark is making himself lunch. The fridge door hangs open. The milk is on the counter, lid off, and the knife is sticking out of the butter.

‘Why didn’t you wake me?’ she asks him.

‘I did,’ he grins. He hasn’t shaved; she likes him this way and he knows it. ‘You told me to piss off.’

‘I don’t remember,’ says Beth, although it sounds like her MO. She drops a teabag into a mug, knowing even as she does that she won’t have time to finish drinking it. A jumping electric pulse snags her attention; the clock on the oven is flashing zeros. Same with the microwave. The radio is stuck on 3.19.

‘All the clocks have stopped,’ she says. ‘In the whole house.’

‘Probably just a fuse or something,’ says Mark, wrapping his sandwich. He hasn’t made anything for Beth, but she wouldn’t have time to eat it anyway.

Chloe is eating cereal and flicking through a magazine. ‘Mum, I’ve got a temperature,’ she says.

‘No, you haven’t,’ says Beth, without bothering to check.

‘I’m. Not. Going,’ Chloe whinges, but her hair, an immaculate blonde plait, and the perfectly applied make-up tell Beth that she knew this battle was a losing one from the off. You can’t kid a kidder. She remembers herself at this age – exactly this age, almost to the day – missing school to meet Mark. There’s no way she’s letting history repeat itself.

Before Chloe can come up with a counter-argument, Beth’s mum bustles through the back door, calling hellos and carrying a bowlful of eggs. She sets it down on the worktop next to – oh, for God’s sake, thinks Beth – Danny’s lunchbox. It’s not like him to forget his packed lunch. Perhaps the effort of making his bed was too much for him. She’ll have to drop it off on her way into work. Like she’s not going to be late enough already.

‘Love you zillions, babe,’ says Mark, kissing Chloe on the top of her head. It must be the millionth – the zillionth? – time Chloe has heard this family phrase, and she rolls her eyes, but when Mark turns to leave and she thinks no one is looking, she allows herself a small, secret smile. Then she tries on the temperature trick with her grandmother, who puts her hand on Chloe’s smooth brow, but it’s just for show. Liz has been through all this twice now and is even less likely to fall for it than Beth.

Mark’s out of the door, to catch his usual lift with Nigel, and his goodbye kiss is quick. He tastes of tea and cereal.

‘Did you see Danny?’ Beth shouts at his back.

‘He’d already gone!’ he throws over his shoulder. ‘I’m late!’

He leaves Beth standing in the kitchen, Danny’s lunchbox in her hand.

Detective Sergeant Ellie Miller’s work suit feels weird and stiff after three weeks in a bikini and sarong, but they’ve brought the Florida sunshine back home with them. Broadchurch High Street shimmers in the early morning haze and everyone’s in a good mood. The sky is cloudless and people are feeling brave enough to put out signs and set up stalls in the street.

She’s glad to be back, and not only because she knows that good news awaits her in the station. It feels right to be here, to be home again. This is Ellie’s street, her old beat, although it’s a long time since she’s been in uniform.

She pushes Fred in the buggy, a bag of duty-free goodies for the gang slung over one handle. At the end of the road, she’ll hand the buggy over to Joe, who’ll walk Tom the rest of the way to school. For now, Joe has Tom in a loose headlock and they’re both laughing. They are reflected, Ellie and her boys, in the plate-glass window of the tourist office. Her sons are so different; Fred’s got her dark curly hair while Tom’s got choirboy looks. His blond hair is just like Joe’s was before his hairline started to recede and he did the dignified thing and buzzed it all off.