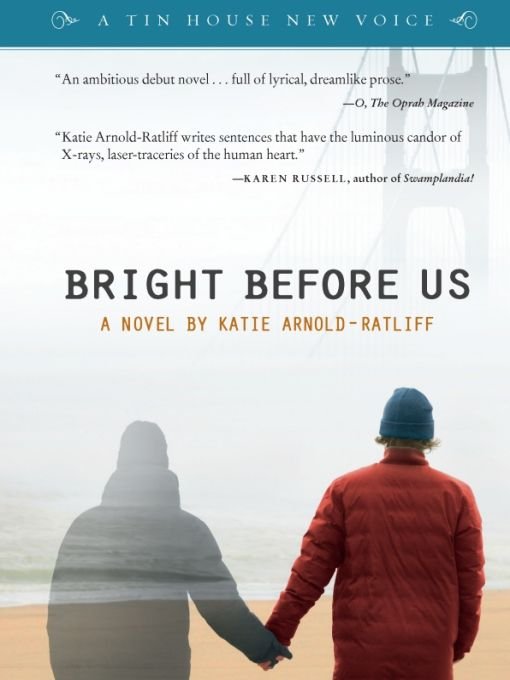

Bright Before Us

Authors: Katie Arnold-Ratliff

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

the face of love ... is the face turning away.

âLOUISE GLÃCK, “LOVER OF FLOWERS”

1

W

e hadn't expected it; the sky had been clear. But as the afternoon waned, clouds converged above the beach, and then the first shocks of rain came down stinging. Soon the wind picked up, and the drops collected in pools. Most of the kids were in short sleeves. I hadn't thought to bring umbrellas. I crouched in the downpour, waiting out the clock, watching the two men in the stranded boat.

e hadn't expected it; the sky had been clear. But as the afternoon waned, clouds converged above the beach, and then the first shocks of rain came down stinging. Soon the wind picked up, and the drops collected in pools. Most of the kids were in short sleeves. I hadn't thought to bring umbrellas. I crouched in the downpour, waiting out the clock, watching the two men in the stranded boat.

They were thirty feet away in a deep and narrow cove, edged by the sand on one side and a rock wall on the other. Their boat bobbed gently, their fishing rods shimmying in the wind. They had just set off for deeper waters, but hadn't gotten far before the motor cut out. As the older man stood with an appraising scowl, his puffed vest darkening with water, the younger man ripped at the pull-cord. Nothing happened. They would have to wade ashore.

It was, on warm weekends, a popular beach. On past trips I had seen teenagers negotiate the jagged rocks in

flip-flops, lifting starfish from suctioned slumber to chuck them into the surf. But it was a Friday afternoon, so there was just me, the two parents who had come to help, and my two dozen second graders. For a listless hour, as we moved incrementally down the beach, my students inspected the kelp-littered dunes with clipboards in hand, making tick marks on their flora observation lists and rubbing their noses with their palms. Now, I wiped the water from my wristwatch and folded my soggy newspaper, ready to call it a day and begin the weekend. It was close enough, I reasoned, to when we had planned to leave.

flip-flops, lifting starfish from suctioned slumber to chuck them into the surf. But it was a Friday afternoon, so there was just me, the two parents who had come to help, and my two dozen second graders. For a listless hour, as we moved incrementally down the beach, my students inspected the kelp-littered dunes with clipboards in hand, making tick marks on their flora observation lists and rubbing their noses with their palms. Now, I wiped the water from my wristwatch and folded my soggy newspaper, ready to call it a day and begin the weekend. It was close enough, I reasoned, to when we had planned to leave.

One of the parents walked overâMr. Noel, a burly, hulking creature built like a linebacker.

Mr. Mason,

he barked,

I'm getting my umbrella. Then we'll line them up?

Mr. Mason,

he barked,

I'm getting my umbrella. Then we'll line them up?

I scanned the beach for the other chaperone.

Where's Mrs. Stone?

Where's Mrs. Stone?

She went to get her daughter's coat,

he said.

You'll be okay alone for a minute?

he said.

You'll be okay alone for a minute?

I noddedâI'm alone with them every day, I thoughtâand he took off at a jog toward the bus; with his jacket pulled high above him he looked headless. As I watched him, one of my students approached me. Since the beginning of the year, eight months earlier, I had worried about herâEmma was thin to the point of frailty, and when I spoke, her eyes remained unfocused, as though she were blindly aiming her face toward the sound. I would call her house to arrange conferences or check up on unreturned permission slips, and listen to the phone ring and ring. Her mother hadn't dressed her for the weather. She was shivering.

Can I please go to the bus?

She pointed to Mr. Noel, who was halfway to the parking lot.

Caleb's dad is going.

She pointed to Mr. Noel, who was halfway to the parking lot.

Caleb's dad is going.

You have to line up like everybody else,

I said, shoving the newspaper into my backpack.

I'm blowing the whistle in three minutes.

I said, shoving the newspaper into my backpack.

I'm blowing the whistle in three minutes.

She began the tantrum dance, her clipboard against her chest.

Consult some classmates until departure time,

I said.

Scientists collaborate, remember? Go share your findings.

I said.

Scientists collaborate, remember? Go share your findings.

I didn't find nothing, Mr. Mason,

Emma said.

I don't even see what's here to find.

Emma said.

I don't even see what's here to find.

I hesitated, then unzipped my jacket and gave it to her. In seconds the rain had pasted my shirt to my back. I glanced at the men in the boat, and then, in the foreground, the children. I felt myself tense.

They had gathered into one still group.

I heard shouting. The men in the boat were now both standing, their vessel rocking as they waved their arms. I took a step forward. The childrenânearly every oneâturned around, several mouths open in alarm. A few of them broke away and ran in my direction, their feet failing beneath them in little stumbles.

Mr. Mason,

they said in chorus. I could see Jacob panting, and as they reached me I heard the characteristic rasp, the beginnings of an asthma attack curling around his chest.

Mr. Mason, Mr. Mason.

Mr. Mason,

they said in chorus. I could see Jacob panting, and as they reached me I heard the characteristic rasp, the beginnings of an asthma attack curling around his chest.

Mr. Mason, Mr. Mason.

I took off at a run, waving to the men in the boat and shouting,

I've got it

, not knowing what that meant. I hollered for the children to go immediately to the bus, my voice shrill, unmistakably panicked. The rest of the children at the water's edge mostly dispersed, starting toward the parking lot, but a few remained, still looking down at whatever was there. I called up the beach for Mr. Noel and Mrs. Stone. They were out of earshot. I barked at Emma,

behind me now,

Go get them

, and as she ran up the beach in my jacket the sleeves grazed the sand. I paused midrun, remembering Jacob.

Someone go in my backpack!

I yelled.

Inhaler, get his inhaler.

I didn't wait to make sure someone did as I asked.

I've got it

, not knowing what that meant. I hollered for the children to go immediately to the bus, my voice shrill, unmistakably panicked. The rest of the children at the water's edge mostly dispersed, starting toward the parking lot, but a few remained, still looking down at whatever was there. I called up the beach for Mr. Noel and Mrs. Stone. They were out of earshot. I barked at Emma,

behind me now,

Go get them

, and as she ran up the beach in my jacket the sleeves grazed the sand. I paused midrun, remembering Jacob.

Someone go in my backpack!

I yelled.

Inhaler, get his inhaler.

I didn't wait to make sure someone did as I asked.

One of them is hurt, I thought. Somebody's head is cracked open. A tableau unfurledâthe sound of sirens, the arrival of an ambulance. The things I had learned in first aid returned to me:

Assess responsiveness. Press firmly on the wound.

Assess responsiveness. Press firmly on the wound.

I squinted at the water; my feet moved slowly in the sand. The boat was now empty. Then I spotted the two men, wading ashore, chest-deep in the gray inlet. One of the kids fell in, I thought. He's filling with water.

Tilt the head with two fingers under the chin. Breathe for him until help arrives.

Sharp points pressed into the soles of my sneakers as I stepped over the rocks at the cove's mouth. The gaze of the four remaining childrenâJeffrey, Marcus, Edmund, and Benjaminâremained fixed on the place where the water met the sand.

Go,

I said, and though I was in motion, I saw it plain as anything: they hesitated. I snapped,

Get over there

, and watched them move toward the dunes. I stepped forward, headlong and terrified.

Tilt the head with two fingers under the chin. Breathe for him until help arrives.

Sharp points pressed into the soles of my sneakers as I stepped over the rocks at the cove's mouth. The gaze of the four remaining childrenâJeffrey, Marcus, Edmund, and Benjaminâremained fixed on the place where the water met the sand.

Go,

I said, and though I was in motion, I saw it plain as anything: they hesitated. I snapped,

Get over there

, and watched them move toward the dunes. I stepped forward, headlong and terrified.

First I saw the flies. They were giddy, drunk on what they had found, big and overfed. They were indifferent to my presence, letting me step into them. I no longer remember the smell, only what it did to me. I doubled over. The tableau evaporated. There would be no CPR, no wound to staunch. I knew what I would find. I looked back, delaying. Most of the kids were going to the bus, but others stood where I had been sitting, staring back at

me. Jacob was coughing frantically, inhaler in hand. He doubled over, desperate for air. I took another step and saw an outcropping of damp wood half-buried in the sand, surrounded by tiny footprints. Bunches of yellow grass wavered in the wind. And a few feet away, beside a slick tangle of brown kelp, was the body.

me. Jacob was coughing frantically, inhaler in hand. He doubled over, desperate for air. I took another step and saw an outcropping of damp wood half-buried in the sand, surrounded by tiny footprints. Bunches of yellow grass wavered in the wind. And a few feet away, beside a slick tangle of brown kelp, was the body.

Â

I see myself as the children must have seen me: a young man stepping cautiously forward, rocks and reeds obscuring his bottom half. His face distorts as he bends at the waist, his palm goes to his open mouth, and then the back of that same hand moves to his nose. The children are afraid. Unexpected events frighten them. But they look at the man and they are, in a small way, put at ease. They look at him and think, He's our teacher.

And then they hear him scream. And as two men emerge dripping from the water and pull him away, the children drop their clipboards. They do what their teacher has commanded them to do whenever they feel they are in danger: they run.

Roughly one year earlier, I had received my teaching certificate in a quiet ceremony at a local state college. I secured a job in the struggling district with unsettling ease, and began looking for holes in the prescribed curriculum that I could fill with art, the People's History, the teaching of tolerance. At home, I practiced finger painting, free-association writing, explosive science experiments, a segment on cooking. I swore I would take my students outside no matter the season; we

would do a unit on international sports, like jai alai and cricket. I would teach them the silly camp songs of my youthâ

Fish and chips and vinegar, vinegar, vinegar.

I stood in front of the medicine cabinet mirror and practiced my enthusiastic lectures, my voice low so Greta wouldn't hear me from the bedroom. I perfected faces to use when they spoke, so they would know that I was really, truly listening to them.

would do a unit on international sports, like jai alai and cricket. I would teach them the silly camp songs of my youthâ

Fish and chips and vinegar, vinegar, vinegar.

I stood in front of the medicine cabinet mirror and practiced my enthusiastic lectures, my voice low so Greta wouldn't hear me from the bedroom. I perfected faces to use when they spoke, so they would know that I was really, truly listening to them.

I could see the San Francisco Bay from the roof of the school building, the dividing line between gray sky and gray water nearly indistinguishable. I occasionally left Greta in our bed before dawn to drink my coffee up there in a lawn chair, staring down the sun as it rose over the playground. Sometimes I went up there to grade homework as the evening wind kicked up, watching stragglers play foursquare while waiting for their parents. I knew I could be seen from the apartments nearby, and that I wasn't hard to peg: a young guy just starting out as a teacher, his wrinkled clothes flecked with last week's tempera paint, crumbling sneakers stained with soccerfield mud. With my conspicuous glasses and purplerimmed eyes, I looked the part.

Large-scale additions had been made to Hawthorne Elementary in the fifties, accommodating the bulge of children born after their fathers returned en masse from the war. The dismal chunky-block design betrayed its quick, utilitarian construction: it was all cement and stucco, later accompanied by a sea of prefab portable classrooms huddled on the former kickball diamond. But I was lucky enough to be placed in the older wing. Tall dark-wood pillars anchored my classroom, their proximity to adjoining walls creating odd nooksâone I used for

a storage area, another for a small study lab. The interior was paneled in that same dark wood, like a saloon.

a storage area, another for a small study lab. The interior was paneled in that same dark wood, like a saloon.

On my first day, I was surprised by my confidence; nervousness had always been my default setting, but that morning I couldn't wait to get started. I arrived long before the children did, and sat staring up at the posters I had chosen: Martin Luther King Jr., a lesser known Matisse, Einstein with his tongue out. I realized, too tired to fix it, that they were hung crookedly. I had put them up hastily days earlier, preparing like mad but slowed by the unrelenting heat. Though outside it was a mild September, the room was stuck at eighty degrees, and the oscillating fan I had brought barely moved the air. But the lessons were planned, the books were on the shelves, and I marveled: whatever happened in there would happen because of me.

My students sat in small blue chairs at tables rather than individual desks, each of the six tables named for a state. I was the president, and they voted on things like where to go for field trips, whether we should play dodgeball or softball in afternoon gym, chalkboards versus whiteboards. The thrill they experienced when given a choice was immense. Their wonder, too, came easily, and was wholly uncomplicated. They cried when I read them

Charlotte's Web

, viewed repro impressionist paintings with pious reverence. When we made buffalo stew for the unit on California's Native Americans, they leaned over the pot like we were cooking up magic. Those first months, I swelled with something unfamiliar: a secure knowledge of the good I was doing.

Charlotte's Web

, viewed repro impressionist paintings with pious reverence. When we made buffalo stew for the unit on California's Native Americans, they leaned over the pot like we were cooking up magic. Those first months, I swelled with something unfamiliar: a secure knowledge of the good I was doing.

Other books

Hero of Slaves by Joshua P. Simon

Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief by Lawrence Wright

Hotel Ladd by Dianne Venetta

Her Lifeline: (A Romantic Suspense) by Chandler, Danica

Breed True by Gem Sivad

For Love of Country by William C. Hammond

The Invasion by K. A. Applegate

Blended Hearts #2 (An Interracial Stepbrother Romance Book) by Alycia Taylor

Turkey Monster Thanksgiving by Anne Warren Smith

Gwynneth Ever After by Linda Poitevin