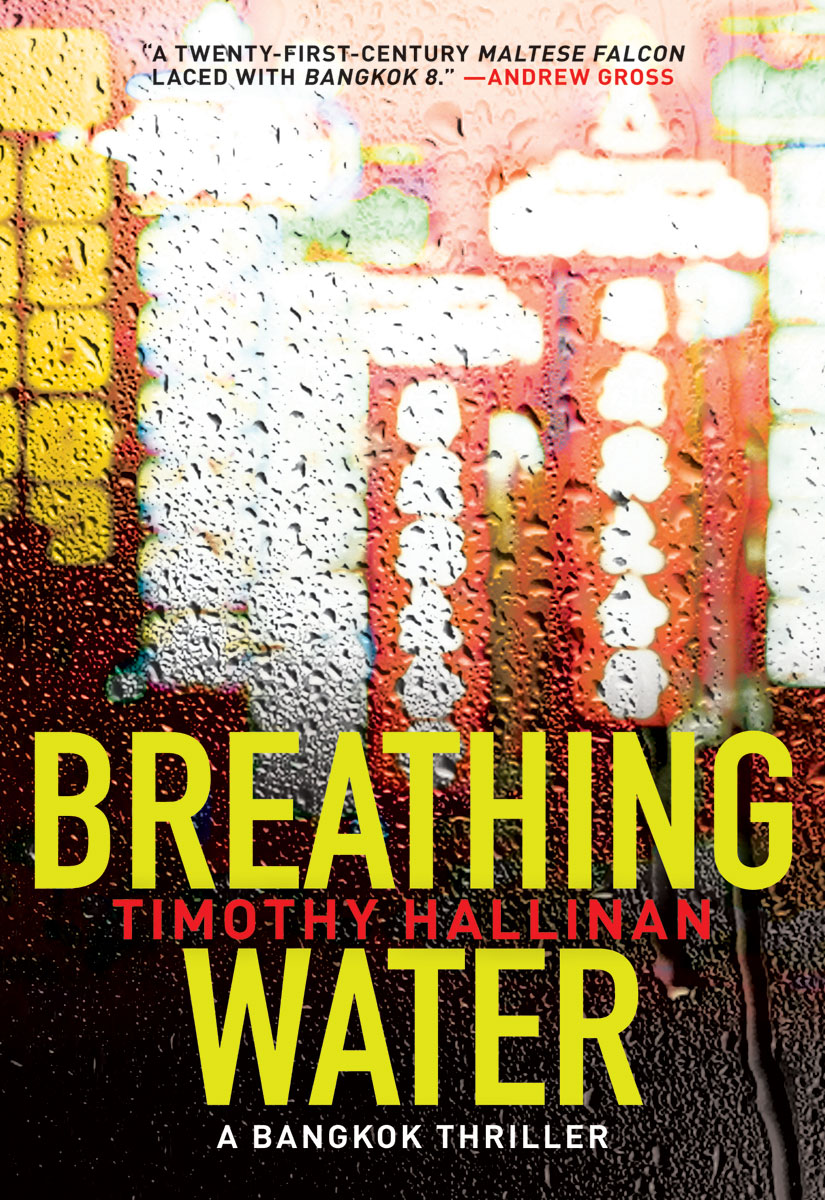

Breathing Water

Authors: Timothy Hallinan

Timothy Hallinan

This book is dedicated to the memory of Raleigh Philp,

who left behind an ever-widening wake of inspiration,

and to Alicia Aguayo from her

hijito

The Gulf

Pinch It

Mud Between Her Toes

The Big Guy

They Could Be Anywhere

All In

Mound of Venus

The Silk Room

Six Separate Hells

A Towel and a Frown

Or What?

Peep

The Chuckle Is a Perfectly Acceptable Form of Laughter

They Dimple the Surface

The First Paradise

No Witnesses

Fair

Charm Doesn’t Make the Cut

The Furniture Takes a Vote

Canaries

Wrecking Ball

Net Profits

Buttercup

Close Enough

The Edge

Luck Will Have Nothing to Do with It

Like He Ate a Grenade

There’s Another One Gone

This Place Was His Forest

The Queen of Patpong

So He Likes Sad Music

You Couldn’t Comb It with a Tractor

All the Way Down

A Man Who Has Just Been Hit by a Train

Innocent as a Dusting of Snow

If He’s a Friend, He’ll Wait

You’ll Probably Be Sterile

Off the Board

Head-On

I Might as Well Be Fluorescent

Nobody Sees Street Kids

Replay

It Corrupts the Corruptible

Off to Brunch

Open Season

She Has a Different Life Now

The Old Skyrocket

You’re Not Hopeless After All

It’s Hard to Put a Positive Spin on Mass Murder

Kinder That Way

Waiting Patiently for Blood

At the Bottom of the Ocean

A Formless Nimbus of Light

News from the Sun

THE GULF

Pinch It

T

he man behind the desk is a dim shape framed in blinding light, a god emerging from the brilliance of infinity. The god says, “Why not the bars? You’re pretty enough.”

The girl has worked a finger into the ragged hole in the left knee of her jeans. The knee got scraped when the two men grabbed her, and she avoids the raw flesh. She raises a hand to shade her eyes so she can look at him, but the light is too bright. “I can’t. I tried for two nights. I can’t do it.”

“You’ll get used to it.” The god puts a foot on the desk. The foot is shielded from the light by the bulk of his body, and she can see that it is shod in a very thin, very pale loafer. The sole is so shiny that the shoe might never have been worn before. The shoe probably cost more than the girl’s house.

The girl says, “I don’t want to get used to it.” She shifts a few inches right on the couch, trying to avoid the light.

“It’s a lot more money. Money you could send home.”

“Home is gone,” the girl says.

That’s a trifle, and he waves it away. “Even better. You could buy clothes, jewelry, a nice phone. I could put you into a bar tonight.”

The girl just looks down and works her finger around inside the hole. The skin around the scraped knee is farm-dark, as dark as the skin on her hand.

“Okay,” the man says. “Up to you.” He lights a cigarette, the flame briefly revealing a hard face with small, thick-lidded eyes, broad nostrils, pitted skin, oiled hair. Not a god, then, unless very well disguised. He waves the smoke away, toward her. The smoke catches the glare to form a pale nimbus like the little clouds at which farmers aim prayers in the thin-dirt northeast, where the girl comes from. “But this isn’t easy either,” the man says.

She pulls her head back slightly from the smoke. “I don’t care.”

The man drags on the cigarette again and puts it out, only two puffs down. Then he leans back in his chair, perilously close to the floor-to-ceiling window behind him. “Don’t like the light, do you? Don’t like to be looked at. Must be a problem with a face like yours. You’re worth looking at.”

The girl says, “Why do you sit there? It’s not polite to make your visitors go blind.”

“I’m not a polite guy,” says the man behind the desk. “But it’s not my fault. I put my desk here before they silvered those windows.” The building across Sathorn Road, a sea-green spire, has reflective coating on all its windows, creating eighteen stories of mirrors that catch the falling sun early every evening. “It’s fine in the morning,” he says. “It’s just now that it gets a little bright.”

“It’s rude.”

The man behind the desk says, “So fucking what?” He pulls his foot off the desk and lets the back of the chair snap upright. “You don’t like it, go somewhere else.”

The girl lowers her head. After a moment she says, “If I try to beg, I’ll just get dragged back here.”

The man sits motionless. The light in the room dims slightly as the sun begins to drop behind the rooftops. Then he says, “That’s right.” He takes out a new cigarette and puts it in his mouth. “We get forty percent. Pratunam.”

She tries to meet his eyes, but the reflections are still too bright. “I’m sorry?”

“Pra…tu…nam,” he says slowly, enunciating each syllable as though she is stupid. “Don’t you even know where Pratunam is?”

She starts to shake her head and stops. “I can find it.”

“You won’t have to find it. You’ll be taken there. You can’t sit just anywhere. You’ll work the pavement we give you. Move around and you’ll probably get beat up, or even brought back here.” He takes the cigarette out of his mouth, looks at it, and breaks it in half. He drops the pieces irritably into the ashtray.

“Is it a good place?”

“Lot of tourists,” he says. “I wouldn’t give it to you if you weren’t pretty.” He picks up the half of the cigarette with the filter on it, puts it in his mouth, and lights it. Then he reaches under the desk and does something, and the girl hears the lock on the door snap closed. “You want to do something nice for me?”

“No,” the girl says. “If I wanted to do that, I’d work in the bar.”

“I could make you.”

The girl says, “You could get a fingernail in your eye, too.”

The man regards her for a moment and then grunts. The hand goes back under the desk, and the lock clicks again. “Ahh, you’d probably be a dead fish anyway.” He takes a deep drag and scrubs the tip of the cigarette against the bottom of the ashtray, scribbles something on a pad, rips off the page, and holds it out. His eyes follow her as she gets up to take it. “It’s an address,” he says. “Go there tonight, you can sleep there. We’ll pick you up at six-thirty in the morning. You’ll work from seven to four, when the night girl takes over.” He glances at a gold watch, as thin as a dime, on his right wrist. In English he says, “How’s your English?”

“Can talk some.”

“Can you say ‘Please, sir’? ‘Please, ma’am’? ‘Hungry’?”

“Please, sir,” the girl says. “Please, ma’am.” A flush of color mounts her dark cheeks. “Hungry.”

“Good,” the man says. “Go away.”

She turns to go, and his phone buzzes. He picks up the receiver.

“What?” he says. Then he says to the girl, “Wait.” Into the receiver he says, “Good. Bring it in.” A moment later an immaculately groomed young woman in a silk business suit comes in, carrying a bundle of rags. She holds it away from her, her mouth pulled tight, as though there are insects crawling on it.

“Give it to her,” the man says. “And you,” he says, “don’t lose it and

don’t drop it

. These things don’t grow on trees.”

The young woman glances without interest at the girl with the torn jeans and hands the bundle to her. The bundle is surprisingly heavy, and wet.

The girl opens one end, and a tiny face peers up at her.

“But…” she says. “Wait. This…this isn’t—”

“Just be careful with it,” the man says. “Anything happens to it, you’ll be working on your back for years.”

“But I can’t—”

“What’s the matter with you? Don’t you have brothers and sisters? Didn’t you spend half your life wiping noses? Just carry it around on your hip or something. Be a village girl again.” To the woman in the suit, he says, “Give her some money and put it on the books. What’s your name?” he asks the girl holding the baby.

“Da.”

“Buy some milk and some throwaway diapers. A towel. Wet wipes. Get a small bottle of whiskey and put a little in the milk at night to knock the baby out, or you won’t get any sleep. Dip the corner of the towel in the milk and let it suck. Get a blanket to sit on. Got it?”

“I can’t keep this.”

“Don’t be silly.” The man gets up, crosses the office, and opens the door, waving her out with his free hand. “No foreigner can walk past a girl with a baby,” the man says. “When there are foreign women around, pinch it behind the knee. The crying is good for an extra ten, twenty baht.”

Dazed, holding the wet bundle away from her T-shirt, Da goes to the door.

“We’ll be watching you,” the man says. “Sixty for you, forty for us. Try to pocket anything and we’ll know. And then you won’t be happy at all.”

“I don’t steal,” Da says.

“Of course not.” The man returns to his desk in the darkening office. “And remember,” he says. “Pinch it.”

FOUR MINUTES LATER

Da is on the sidewalk, with 250 baht in her pocket and a wet baby in her arms. She walks through the lengthening shadows at the aimless pace of someone with nowhere to go, someone lis

tening to private voices. Well-dressed men and women, just freed from the offices and cubicles of Sathorn Road, push impatiently past her.

Da has carried a baby as long as she can remember. The infant is a familiar weight in her arms. She protects it instinctively by crossing her wrists beneath it, bringing her elbows close to her sides, and keeping her eyes directly in front of her so she won’t bump into anything. In her village she would have been looking for a snake, a stone in the road, a hole opened up by the rain. Here she doesn’t know what she’s looking for.

But she’s so occupied in looking for it that she doesn’t see the dirty, ragged, long-haired boy who pushes past her with the sweating

farang

man in tow, doesn’t see the boy turn to follow her with his eyes fixed on the damp bundle pressed to her chest, watching her as though nothing in the world were more interesting.