Breasts (2 page)

Authors: Florence Williams

Tags: #Life science, women's studies, health, women's health, environmental science

What I found was not only unsettling and profound, but also at times funny and provocative. Take, for example, the Barbie debate. Women with more hourglass waist-to-hip-to-breast ratios produce slightly higher levels of estrogen as a general rule. Sounds desirable, right? But those women may also be more likely to cheat on their mates and to get breast cancer. In fact, women with fewer curves can hold their own just fine, thank you, as some indignant researchers have pointed out. In times of trouble and stress, it may be these women—with their slightly higher levels of so-called male hormones—who can bring home the mastodon and slap competitors upside the head. That’s pretty sexy. (There’s an interesting male corollary to this: men with bigger muscles attract more mates but appear to have weaker immune systems. Beauty comes at a price.)

I learned that breast milk, once the magic mojo of evolution, might now actually be devolving us, holding back our potential. Toxins in breast milk have been associated with lower IQ, compromised immunity, behavioral problems, and cancer. Our modern world is not just contaminating our breast milk. It is also reshaping our children, contributing to earlier puberty in girls. Breasts are often one of the first signs of sexual development. When girls sprout breasts earlier, they face an increased risk of breast cancer later, for

reasons I will explore. In fact, at every life stage of the breast, from infancy to puberty to pregnancy to breast-feeding to menopause, our modern environment has left a mark.

As civilization marches on, we have also steered breasts away from their natural lives by hiring wet nurses, entering nunneries, controlling our reproduction, and seeking to alter the breast cosmetically. After her mastectomy in the early 1970s, my grandmother wore a breast “prosthesis” that bore the silhouette and heft of a nuclear weapon head. Ironically, these devices were promoted—and later designed—by none other than the inventor of Barbie, Ruth Handler, herself a breast cancer patient. Today’s fake and enhanced breasts are far more naturalistic. Nearly everyone wants a piece. Wonderbra sales in the United States top $70 million annually.

In countless ways, modernity has been good for women, but it hasn’t always been so good for our breasts. The global rise in the incidence of breast cancer is partly influenced by better diagnostics and an aging population. But those factors aren’t enough to explain it. The wealthiest industrialized countries have the highest rates of breast cancer in the world. Family history accounts for only about 10 percent of breast cancers. Most women (and increasingly, men) who get the disease are the first in their families to do so. Something else is going on, and that something else is linked to modern life, from the furniture we sit on to our reproductive choices, to the pills we take, to the foods we eat.

In addition to my family history, I, like so many women, have other risk factors for the disease, including delayed childbirth, a small number of pregnancies, and, because of those two things, many decades of uninterrupted, free-circulating estrogen. I took birth control pills before I was out of my teens. Like most Americans, I have slightly low vitamin D levels, another hazard chalked up to

modern life. All told, I’m pretty average, and so are my breasts. In writing and researching this book, I sometimes used my body as a proxy for modern women, testing it for commonly known and suspected carcinogens and holding my breasts up to various scanners, screens, and probes. My daughter, Annabel, gamely signed on for some experiments as well.

At its heart,

Breasts

is an environmental history of a body part. It is the story of how our breasts went from being honed by the environment to being harmed by it. It is part biology, part anthropology, and part medical journalism. The book’s publication marks the fiftieth anniversary of two significant milestones in the natural history of breasts whose themes will recur here: the publication of Rachel Carson’s

Silent Spring

(which recounted how industrial chemicals were altering biological systems) and the first silicone implant surgery in Houston, Texas, in a woman who really just wanted an ear tuck.

Why should we seek to know the breast better? Why should we care? There are several reasons. One, as individuals and as a culture, we love them and we owe them as much. Two, we want to protect and safeguard them, and to do that, we need to understand how they work and how they malfunction. Three, they are more important than we realize. Breasts are bellwethers for the changing health of people. If we’re becoming more infertile, producing increasingly contaminated breast milk, reaching puberty earlier and menopause later, can we fulfill our potential as a species? Are our breasts now the leading soft edge of our devolution? If so, can we restore them to their prelapsarian glory without compromising our modern selves? Breasts carry the burden of the mistakes we have made in our stewardship of the planet, and they alert us to them if we know how to look.

If to have breasts is to be human, then to save them is to save ourselves.

FOR WHOM THE

BELLS TOLL

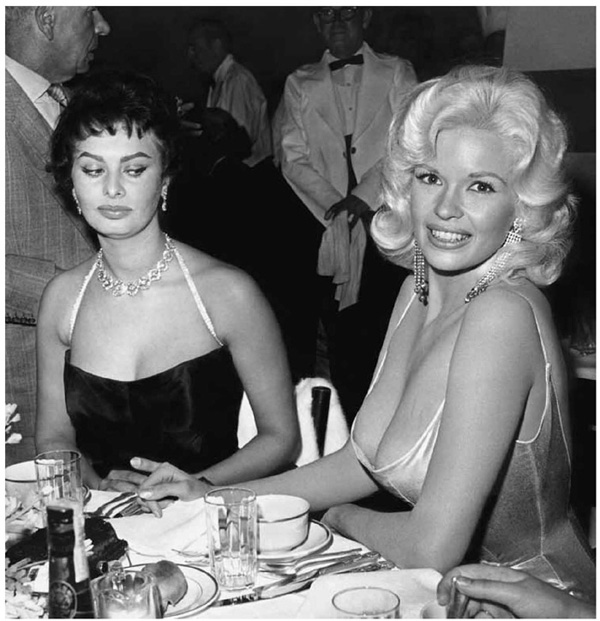

A 41-inch bust and a lot of perseverance will get you more than a cup of coffee—a lot more.

—JAYNE MANSFIELD

[Breasts] are a body part that we didn’t start out with … whole new organs, two of them, tricky to hide or eradicate, attached for all the world to see … twin messengers announcing our lack of control, announcing that Nature has plans for us about which we were not consulted.

— FRANCINE PROSE,

Master Breasts

I

F THERE’S ONE THING STARLETS LIKE JAYNE MANSFIELD AND

Mae West understood, it was the power of their ample endowments. In her 1959 memoir,

Goodness Had Nothing to Do with It,

West writes that beginning in her teens, she regularly rubbed cocoa butter on her breasts, then spritzed them with cold water. “This

treatment made them smooth and firm, and developed muscle tone which kept them right up where they were supposed to be.” West has good company in doling out ridiculous breast-enhancing tips. On the Internet, you can find creams, pills, pumps, pectoral exercises, even a YouTube video on how to master the boob-inflating “liquefy tool” in Photoshop.

In our culture at least, big breasts get a lot of attention. So I’m told. I display, or rather, don’t display, the traditional average American size, a B cup.

1

Women I know tell me that having large breasts is like walking around with a neon sign hanging around their necks. Men, women, small children, everyone stares. The eyes linger. Some men pant. It’s not surprising that some anthropologists have called breasts “a signal.” Breasts, they say, must be telling us something about how fit and mature and healthy and maternal their owner is. Why else have them?

All mammals have mammary glands, but no other mammal has “breasts” the way we do, with our pleasant orbs sprouting out of puberty and sticking around regardless of our reproductive status. Our breasts are more than just mammary glands; they include a meaty constellation of fat and connective tissue called stroma. To be functional for nursing an infant, a mammary gland need fill only half an eggshell. Big breasts are not required. Along with bipedalism, speech, and furless skin, breasts in their soft stroma-filled glory are one of humanity’s defining characteristics. But unlike bipedalism and furlessness, breasts are found in only one sex (at least most

of the time). And those kinds of traits, as Darwin pointed out, often evolved as sexual signals to potential mates.

But signals of what, exactly? And does this explain how and why humans won the boob lottery? Many scientists seem to think so, and they have devoted large chunks of their careers to answering these questions. One thing is clear: it’s rather fun trying to find out. It’s not especially hard to design studies showing that men like breasts. What’s much trickier is proving that it actually means anything in evolutionary terms.

I was hoping the answers might lie with the creative experiments of Alan and Barnaby Dixson, a father-son team of institutionally supported breast watchers. Both based in Wellington, New Zealand, together they’ve published papers on male preferences for size, shape, and areola color and on female physique and sexual attractiveness in places such as Samoa, Papua New Guinea, Cameroon, and China. Alan, a distinguished primatologist and former science director of the San Diego Zoo, brings a specialty in primate sexuality to their shared project, while Barnaby, a newly minted Ph.D. in cultural anthropology, has a knack for computer graphics and a fresh zeal for fieldwork.

I first met Barnaby on a blustery fall day in Wellington. At twenty-six, his curly auburn hair falling around the collar of a fisherman’s sweater, he was very earnest. He walked around with a distracted air and wrinkled brow, and often misplaced things, such as parking receipts. It’s not easy being a sex-signaling expert. “Sometimes people think I’m using the government’s money to look at breasts. They misunderstand what we do,” said Barnaby, who’s tall and gangly and speaks with a crisp British accent. As Barnaby pointed out, in places like Samoa, which is now very missionized,

it can be a delicate matter asking men to describe which types of breasts they prefer. He said some men think he’s “a perv” and get very angry. He avoids men who have been drinking. And in the academic world, grant money can be hard to come by when there are things like breast cancer research to fund. “I probably should have been a doctor,” he said. “But I’m quite squeamish really.”

Barnaby’s latest digital experiment employed an EyeLink 1000 eye-tracking machine and a suite of specialized software. The sixty-thousand-dollar piece of equipment lives in a small, nondescript room labeled “Perception/Attention Lab” in the psychology department at Victoria University. It looked like something you’d find in an optometrist’s exam room. You place your chin in the chin cradle and your forehead against the forehead rest. Then you look through little lenses. Instead of seeing an alphabet pyramid, though, your eyes meet images of naked women flashing on a computer screen. If all eye exams worked like this, men would surely get their vision screened in a timely fashion.

On the day I visited the lab, an ecology graduate student named Roan was game to volunteer. Wearing jeans and a baggy T-shirt, he patiently looked through the eye-tracker as Barnaby calibrated the machine. Then Barnaby explained the test. Roan would be looking at six images, all of the same comely model, but digitally “morphed” to look different. Roan would have five seconds to view each image, and then he’d be asked to rank it on a scale of one to six, from least attractive to most, using a keyboard. The images would have smaller and larger breasts and various waist-to-hip ratios. These two metrics, the breasts and the so-called WHR (essentially a measure of curviness), are the lingua franca of “attractiveness studies,” which is, believe it or not, a recognized subspecialty of anthropology,

sociobiology, and neuropsychology. The theory is that how males and females size each other up can tell us something about how we evolved and who we are.

The eye-tracker doesn’t lie. It would show exactly

where

on the body Roan was looking while making up his mind. As Barnaby had explained to me earlier, the machine would measure the travel of Roan’s pupils within one-hundredth of a degree, and would record how long his gaze lingered on each body part. “The beauty of the eye-tracking machine is that it allows you to get some measure of behavioral response. You can measure, literally, the behavior of the eye during attractiveness judgment,” Barnaby had said.

Roan began staring and ranking. The whole thing took a couple of minutes. He looked a little flushed when it was over.

He stuck around to see how he did. Barnaby called up some neat graphics and computations. A series of green rings overlay the model; they represented each time Roan’s eyes lingered for a moment. Some of the rings were on her face, a few on her hips, a whole bunch on her breasts. Barnaby explained them as he reviewed the data. “He starts at the breasts, then looks at the face, then breasts, then pubic region, midriff, face, breasts, face, breasts. Each time the eye rests longer on the breasts.” Roan spent more time gazing at the breasts than elsewhere during each “fixation.” He rated the slimmer images with large breasts as most attractive.

In other words, Roan behaved just as most men do, and just as Jayne Mansfield knew he would. She could have saved Victoria University a chunk of change.

Barnaby’s eye-tracker results may be obvious, but to a scientist, data are key. Barnaby was preparing to publish his study in a journal called

Human Nature.

He believed the work backs up a

relatively well-accepted hypothesis that breasts evolved as signals to provide key information to potential mates. That’s why men’s eyes zoom in on breasts within, oh, about two hundred milliseconds of viewing an image. That’s

milliseconds.

“The overall theory is that youth and fertility are important traits when men and women in ancestral times were selecting a partner,” said Barnaby. “So it makes sense they’ll select for traits that signal mate value, youth, health, fertility.” He believes men find breasts useful. Because men liked these informative, novel, gently pendulous orbs—which originally sprang up in the accidental way all new traits do—they selected mates accordingly. The breasty women were the ones who mated most, or mated with the best males, and so the trait was passed down for all to behold. In the world according to Barnaby, that’s pretty much the end of the story.

I wondered whether Roan subconsciously sensed that cache of health and youth information in a few seconds of ogling.

“Do you tend to be a breast guy?” I asked him.

“Good question.” Roan is a South African who spends his academic time studying rhinos. “Yeah, but not majorly so. It’s not like I’m obsessed, like some guys I’ve met who tend to go on about it. But yeah, I definitely don’t have any problem with them.”

I couldn’t help feeling peeved by the real-world relevance of the eye-tracking study. A man looks at a woman’s hips and breasts for five seconds and decides whether or not to mate with her? Was that how it worked in our deep evolutionary past? Was it how it worked now? And even if it were, did it really explain

why

we have breasts in the first place?

“When you’re meeting a woman, you’re hopefully looking at more than just her breasts,” I said to Barnaby and Roan.

Roan blushed and laughed. “Of course! Cheers!”

“That’s an important point,” interjected Barnaby. “You’re not just going to stare at her breasts.”

“Some people do,” said Roan.

Barnaby felt a need to rescue the conversation. “This is an artificial experiment. It measures what you might call a first-pass filter, just things that are immediately apparent. Then later, when you’re meeting and talking, so many other things factor in, like personality, religious background, socioeconomic status.”

“Sense of humor?” I asked.

“Yeah,” said Roan. “Of course, of course.”

AFTERWARD, WE ATE LUNCH AT THE SMALL, CREEK-SIDE HOME IN

the Wellington hills that Barnaby shared with his girlfriend, Monica, a Canadian graduate student studying bird behavior. She made a fantastic soup out of a roasted New Zealand tuber called kumara. A sign above the kitchen read, “Please do not feed the bear.”

It turns out I wasn’t the only woman whom Barnaby’s work made a little uncomfortable and self-conscious.

“Whenever Barny gives seminars on waist-to-hip ratios, all the women run home afterwards and measure themselves,” said Monica. (Barnaby’s studies and many others have established that men prefer a Marilyn Monroe–esque WHR of .7, meaning the waist is 70 percent the circumference of the hips. Some scientists hypothesize that this magic number represents an optimal level of health and hormones, but the significance of the WHR is highly controversial in the field.)

Barnaby looked mortified. “Yeah, well that’s unfortunate.”

“I measured mine,” offered Monica.

“How did it turn out?” I asked.

“I’m a .75.”

Barnaby himself doesn’t seem immune to his research. He wears, for example, a beard. In his cross-cultural anthropological studies, he has found facial hair to symbolize masculinity and authority. (His father, who teaches at the university and lives one town over with his wife, Amanda, and an eighty-pound English bulldog named Huxley, sports a bushy white mustache.)

Barnaby’s walls boasted several original Alan Dixson drawings, including one of a mandrill and one of a gorilla. Alan illustrates most of his own textbooks, while Barnaby supplies the computer graphics. Alan’s latest book is called

Sexual Selection and the Origins of Human Mating Systems.

In addition to their eight coauthored papers, they share a love of animals and a polite, diffident demeanor.

“Barnaby is like a mini-me of Alan,” said Monica, laughing. Born in England, the younger Dixson grew up in places like Scotland and West Africa, depending on his father’s posts. In Gabon, where Alan ran a primate center and studied sperm competition, Barnaby’s family had a pet monkey, a potto named Percy. Living closely among other animals made their behaviors, sexual and otherwise, seem perfectly normal. Barnaby’s older brother is also a scientist. His specialty is an enormous flightless cricket.

Both Alan and Barnaby believe studying mating behavior and sexual selection in primates can tell us much about our own reproductive organs. For example, men have relatively small testicles compared to other existing primates. Alan has written that this might indicate our early human ancestors were polygamous. (On this topic scholars vehemently disagree with each other. The field of evolutionary studies is a blood sport.)

To the Dixsons, enlarged human breasts, like giant testicles in

chimps or the orangutan’s beard, are “courtship devices” born out of competition and selection. Large testicles produced more sperm, maximizing an individual’s chance that his genes, and not his rival’s, would penetrate the egg of a promiscuous female. The males with the biggest testicles had more descendants, who in turn had bigger testicles. The Dixsons believe beards and enlarged breasts, on the other hand, are seductive “adornments” advertising genetic quality. Those who attracted the best mates had fitter offspring and, ultimately, larger numbers of descendants, and so the traits persisted. This is the essence of sexual selection as posited by Charles Darwin.

“A lot has been written about what breasts might be telling a guy,” said Barnaby. “At its simplest, they’re telling the guy that this is a sexually mature woman. Beyond that, there are a lot of hypotheses. One that I find interesting, based on work on Hadza huntergatherers in Tanzania, is that there could be a profound preference among men for a nubile breast shape.” He explained that as women age and have more successive pregnancies (thus reducing her worth to a new mate), her breasts change. “I’m trying to find a nice way of saying it,” hedged Barnaby, “but age and gravity take their toll. The shape tends to lose its firmness and droops somewhat. This could be something that’s letting a man know about youth and fertility and potential reproductive output.” In other words, guys, go pursue someone a little more worthwhile, biologically speaking.