Breaking News: An Autozombiography (35 page)

Slowly but surely the advance thinned, and the pace of fighting eased. Some of the new people collapsed, puking and wailing. Jay and Al walked around them, checking for wounds, as those on horseback saw to the last few stinkers below. The Chanctonbury Assault was nearly over. Only the dull crunch of Al’s axe and the light whip of Jay’s sword pierced the sound of sobbing and dry heaving, and pretty soon Al came up to me with a sober look on his face.

‘

One of them has got a leg wound. He says it was a blade,’ he whispered. ‘I must admit it doesn’t look like a bite but I thought I’d check with you before doing him.’

‘

Get him in the pit. Everyone’s got to strip, now.’ I turned to the campers. ‘We need to check you all out for wounds again. Take your clothes off. Anyone not willing to do so goes back in the pit. Anyone with a wound – even if it doesn’t look like a bite or a scratch - goes back in the pit. Anyone bitten, well…’

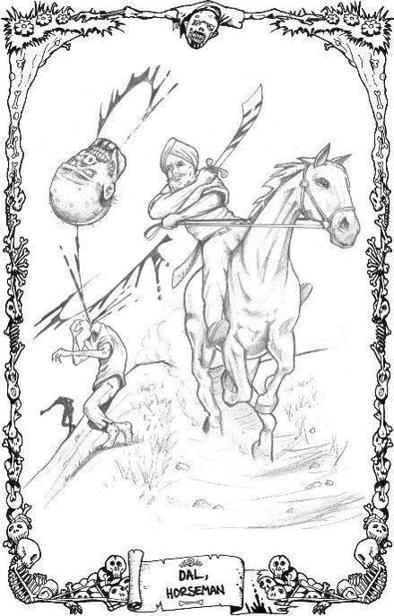

No-one moved. I sensed their disbelief. I was being ruthless and cold, but I was determined not to muck about. We’d got this far. Still no-one moved, as Dal, David and Dawn trotted up to join us. I saw Jay talking to Dal, who motioned to the Goths, before they made their way back down the slope to keep watch. I put my bow and arrow on the floor and undid my trousers. Lou began to remove hers, and Jay and Al weren’t far behind as I pulled off the last of my clothes.

Soon the four of us stood side-by-side, naked and defenceless, looking around us. If ever there was a time for a mutiny, this was it, but Glyn stood up and started to take off his clothes, hauling Debbie to her feet who started to make complaining noises. A few more took their cues. The kids threw their clothes into the air, whooping, burning off adrenalin. Lou, Al, Jay and I picked our weapons up and started to move amongst people. I got accusing looks, as some of the less useful children cowered in their mother’s arms. We weren’t sorting people out into male and female for the benefit of people’s dignity, either.

‘

Pit!’ I heard Al say, levelling his baseball bat at a woman with a strip missing from her arm. ‘We’ll patch you up when you’re in. Go!’ he prodded the woman, who winced her way to the west side of the camp towards the quarantine pits.

‘

You too,’ Al was saying to a middle-aged man.

‘

Nah, it’s a fuckin’ graze. I slipped yesterday.’ He protested.

‘

That looks as fresh as a daisy to me,’ Al snorted. ‘Pit. Now!’

The man turned to walk in the opposite direction to the pits, so Al cracked the back of his head with his bat. With a metallic ping he fell to the ground. Al called to the woman with the flesh wound to take him down with her. A few campers stood to help her, but Al told them to sit back down. One woman was screaming, her leg open to the air. She was fully clothed still, her trouser leg in shreds. Her husband had pulled her away from the freaks that had set upon her, but he just watched now as Jay raised his sword above her head.

Glyn called me over to the pits. They were all full again now; five of them with naked and wounded campers, but the sixth one had a fully-formed zombie in it, lashing out at the chalky walls and gurgling. The urge to feed made him scrabble up the walls, his fingernails stripping away to black stumps. He wasn’t getting out though.

‘

We’ll leave him in there if we can. It might give us the chance to see if they ever fucking stop. Have we actually got enough room for the wounded?’ I asked Glyn.

‘

Sure, there’s five each in A, B and D, six in C and E,’ He said. ‘That one’s pretty much spare.’

‘

Give them all the full four days,’ I told him, and then turned to look into the pits. ‘We’ll bring you the first-aid kits. You all know why you’re in here, so I’ll not apologise. You’ll be out before you know it.’

The rest of the week was sober, with many people mourning relatives or new friends, but we saw no more stinkers on the top, just the usual squirming barricade of weaker ones rasping and scratching at the steep sides of the earth embankments. On the sixth day Lou ran to save a woman who stood at the edge of the ring with arms outstretched, before dropping with a sense of purpose face-first into the heaving ditch. Someone who knew her told me that she had been wracked with guilt, even though she’d saved three other people the day the virus had hit.

Two people in quarantine had been infected after all, seemingly okay until they had fainted and hawked the black sludge down themselves to the screeches of the others in the pits. We’d lassoed them by the necks, thrown axes to the others in the pits, and buried them headless in the graveyard alongside the eighteen citizens who had not survived the Chanctonbury Assault.

[days 0093 – 0098]

It had snowed. It was early October, but usually - even in the depths of winter - we hardly ever got snow this far south. The weather had been weird recently, with mists and sea fog rolling in out of nowhere even on bright, sunny days; and powerful lightning storms, splitting the sky without thunder. There had been sharp frosts too, glistening crystals clinging heavily to the trees and bushes, but this was proper snow, lying thick on the ground. We’d kept the skins of the two-dozen or so animals we’d found and slaughtered, but it would never be enough to keep everyone warm. Ray Mears’ book detailed how to prepare skins properly, and even before it had got really cold we’d made frames and done it all properly; using lime to soften the hair and even mashing the animal’s brains up, and diluting them to treat the skins which made them pliable enough to be used like cloth.

As the temperature traced out the shape of our breath like ghosts and left crystal pearls on cobwebs, we had built heat-reflecting fences on the windward side of all the camp fires and fitted simple chimneys to the roofs of the more substantial buildings so we could actually light fires inside. We’d plugged all the gaps between the logs with mud and moss. We’d also gathered as much hay as we could from a nearby field, for the horses, so a great mound of it sat under the tarpaulin behind the camp. I’d got everyone to take as much as they needed for the floor of their shelters after drying it out by the fire, as it was a little damp even under cover. Around half the forty-four survivors left in the camp had managed to grab sleeping bags or duvets before fleeing, during the scorching weeks after the outbreak hit. No-one had any form of winter clothing with them, but the supplies of those camp members who were killed during The Chanctonbury Assault were plundered for protection against the cold. The kids felt it most, so they got the sheepskins, which only added to their tribal appearance.

The snow did not bode well – we had potentially a further five or six months of this - although the children loved it and soon set about making igloos. They took their time - I suppose the lack of Dick and Dom or X-box, together with the hard work they’d all put into developing the camp, had stretched their attention spans – and they had built three child-sized structures. They’d tried to persuade their parents to let them sleep in them, but they had been told the igloos would be too cold to be safe. I had to disagree, and it was only when I got Glyn’s wife to stick her head inside one of them that she agreed they were much warmer even than the log cabins. To Debbie’s disappointment, the twins now had no excuse not to stay the night in them, so they did so with glee.

After one unsuccessful hunting trip, we all gathered round the fire as night closed in. An earlier snowstorm had fallen thickly from the parchment skies, clouding everything around us in deathly silence, and we could see more dense clouds gathering to the north just as the light failed. Then the dogs howled long and low - I jumped to my feet, awaiting confirmation of an infiltration from someone on security before spurring into action. None came, but the dogs got louder. Right then, as the fresh snowflakes started to fall I saw my parents - dressed in furs and sporting what can only be described as umbrella hats. My parents.

‘

Fucking hell!’ I spluttered.

‘

Language, honestly.’ My mother said.

‘

You were swearing like a dock-worker when you put your ankle out,’ my dad said. Then he turned to me casually. ‘Hullo son.’

‘

What are you doing here? Where did you come from? Where’s Philip?’ I stammered. Lou had stepped up and gave them both a hug.

‘

Hello!’ Lou said. ‘It’s nice to see you. Let me make you both a nice cup of tea.’

‘

Ooh, lovely,’ my mum began, fumbling about inside her battered handbag. ‘I’ve got my special teabags somewhere, hang on.’

Making Contact

[days 0098 – 0153]

My parents were both retired teachers. My mum was head of the science department at one of the ancient private schools dotted around the Downs, whilst my old man taught Graphic Design at the local sixth form college in town. He had even ended up teaching me, to my unfolding horror, and I had met some kids at my own school that had been taught by my mum. They didn’t like her much; they said she was too strict and ‘a cow’, which was about as insulting as children at my school got about each other’s mothers. The kids in the camp, however, found them both highly amusing, and had fallen about laughing at the adapted umbrellas they wore strapped to the top of their hats. My dad made them worse by performing a little tap dance for them, whilst I wished the ground would open up and take me away from the hot-cheeked embarrassment. They were delighted to see Jay’s folks, who they had befriended at our wedding, and my mum declined a dash of Jerry’s rum for her ‘special’ tea (I’ve never asked), which she sipped still steaming. Dad nodded a tot into his, and they sat back to regale everyone with their story. They were arguing briefly about what point to start the story at, but my mother won by beginning the story where she thought best with a sharp ‘shush’.

‘

When they first said some kind of virus had broken out we were already visiting our other son Philip in Bristol - who is fine by the way darling and says ‘hullo’ - when it started to get quite fraught right outside,’ she began, clutching her hair with both hands to illustrate exasperation.

‘

They said it was a biological attack didn’t they at first, then that it was avian influenza! I knew it wasn’t that because my old friend Edie caught it and Edie hates birds; she’s not been near one since her wedding. I won’t bore you with all the gory details but we had to defend St. Ethel’s. What a blooming hoo-ha it all was. Golly.’

St. Ethel’s was a little church tucked away in a forgotten corner of Bristol. My older brother was the caretaker, and he stayed rent-free in a draughty room above the vestry. That way he and his wife could save up for a deposit on a place of their own whilst looking after the creepy old building. He was a fearsomely intelligent man; but gentle, meek and kind with it.

My dad was quite happy to bore us with all the gory details. They’d been in my brother’s flat waiting to go out for lunch when the streets outside erupted. Of course they had begun to let people into the church to seek shelter, find relatives, or to wait for medical treatment; the vicar was nowhere to be seen. Naturally they had let the wounded in too, and the virus had taken hold inside the church. As people had started to get bitten my brother led my parents up the organist’s stairs to the rooms at the top. There they’d stayed, watching the carnage from the upper balconies, letting people up who could prove they hadn’t been bitten. My dad had been the one to realise that the dead were walking first – he’d pushed a chap down the stairs, breaking his neck, but he’d got straight up and come at him again.

They’d been under siege for weeks when the church finally emptied and they had closed the heavy oak doors for the first time. They’d even looted a local store – my parents, looting – so they could restock my brother’s larders. When they decided to leave for home, Philip opted to stay boarded up in the church with his wife, telling my mum and dad that it would give him a good opportunity to finish two of the books he was writing. My parents ventured out into the country, going by car as far as Wiltshire where their petrol ran out. They’d walked the other hundred-odd miles to Worthing. I couldn’t believe what they were telling me.

‘

What do you mean you walked the last hundred miles?’ I demanded.

‘

Well, we put one foot in front of the other in succession. You should try it.’ I was disappointed to hear people laughing – I knew from experience my dad needed no encouragement.

‘

But what did you do about all the walking dead that happened to be roaming about?’

‘

We adapted to the circumstances,’ My old man said sniffily, as if I should have given them more credit. I probably should have, as they had obviously adapted to the circumstances well. He showed me his shooting stick - like a walking stick, but with a fold-out seat for a handle. The other end was pointed, with a collar of metal to prevent you sinking too far into the ground. But, like his hat, he’d decided that some modification would prove useful so he’d sharpened the point and fitted a much wider diameter metal disk. My dad used the point to pierce the breast-plates of advancing stinkers and push them towards the nearest immovable object. Meanwhile my mother – a champion of dissection in the classroom – would push a garden hoe she had found and sharpened into their open mouths and through the backs of their necks, severing the spinal cord. Simple but effective, and their golden rule was, apparently: ‘if there’s more than one - run’. They told me they’d dispatched five hundred on the walk between Stonehenge and Cissbury. My mum accepted her second cup of tea whilst my dad waved the dogs away, who seemed particularly interested in his trousers.