Bread Matters (23 page)

Authors: Andrew Whitley

One of the easiest flours with which to start a natural fermentation is spelt. In its wholemeal version, it seems to carry a generous population of yeasts and bacteria and should reach a usable state in only a few days. As you will have gathered, the start-up sequence is pretty much the same for any sourdough or leaven: mix the flour with some water, keep it warm, add some more from time to time until the organisms are reproducing and fermenting vigorously. For more details, see Starting a rye sourdough on page 160.

Here is how to start a spelt leaven.

Days 1 and 2

50g Wholemeal spelt flour

100g Water

150g Total

Keep this mixture as near to a constant 28°C as you can manage. Ferment for 2 days.

Day 3

150g Starter from Days 1-2

50g Wholemeal spelt flour

50g Water

250g Total

At the end of another day, this leaven should be fermenting nicely. If it is not, give it another Day 3 treatment, tuck it up in a warm place and await developments.

Spelt Bread

I live about 30 miles from Hadrian’s Wall, as the screaming jet flies. At various points along the wall, excavations have revealed evidence of granaries, drying kilns, mills and bakeries. When I became aware of spelt and its significance in the food economy of Ancient Rome, I realised that I could probably make a bread similar to that which was eaten by the legions stationed not far from my bakery 1,800 years earlier. The drying kilns were a clue to the kind of flour used: they would have been needed to roast spelt grain because it is a ‘covered’ wheat, whose husks do not fall off at threshing time. Roman ovens would have been fired with wood, as was mine. Their bread was fermented without the use of baker’s yeast, as was mine. The mechanical dough mixer was the only aspect of our breadmaking that a Roman would not recognise. Then my Classicist brother dug out a recipe from Pliny, which described a bread made with spelt and the juice of raisins.

I am sure that demand for the resulting product had less to do with my fanciful historical musings than the still largely unexplained fact that people who found commercial yeasted wheat bread made them unwell were able to enjoy spelt bread with impunity.

The raisin juice is an optional addition, which provides a little sweetness to counter spelt’s sometimes bitter flavour. It may also provide some fermentable sugars to aid the leavening process. The result is a hearty wholemeal loaf with a markedly stronger flavour than bread made with modern wheat.

Makes 1 large cob

Spelt production leaven

150g Spelt Starter (from above)

200g Wholemeal spelt flour

120g Water

470g Total

Mix everything together into a softish dough at about 27°C. Cover and leave in a warm place for 4 hours. In very warm weather, or if your leaven is very lively, this period of refreshment may need to be reduced to 3 hours or even less. The production leaven is ready when it has expanded appreciably but not collapsed on itself. At the same time as you refresh the leaven, prepare the raisin mush:

Raisin mush

50g Boiling water

50g Raisins

100g Total

Pour the boiling water on to the raisins and let them steep for half an hour or longer. Then whiz them into a fine mush in a blender.

Spelt bread dough

400g Wholemeal spelt flour

7g Sea salt

100g Raisin Mush (from above)

200g Water

300g Production Leaven (from above)

1007g Total

Make a dough with all the ingredients except the production leaven. It will feel quite coarse and stodgy at first, but a few minutes’ kneading will bring a change to the gluten and the dough will hold together better. Add the refreshed spelt leaven and give the dough another few minutes’ kneading. It should finish fairly soft – a bit less so if you intend to prove it freestanding on a baking tray.

Treat it from here like French Country Bread (see pages 182-185) but the final proof will be a bit shorter. Do not expect enormous expansion of the dough. Spelt gluten is not all that strong and the bran in the flour does interfere with the formation of big gas bubbles.

Too many sourdoughs?

This chapter has, so far, described how to produce four different types of sourdough or leaven: rye, wheat, chickpea and spelt. Despite their obvious similarities, there is a danger that my initial claim – that sourdoughs are easy – will be belied by such a proliferation. Pausing only to defend myself with the observation that all these sours are simply flour and water left around for a while, I offer a solution for the home baker who would rather limit the number of tubs festering in the kitchen.

The one and only

The answer is to keep only a rye sourdough going permanently. In my experience, a rye sourdough is the easiest to get going, the quickest to regenerate and the most resilient. Any of the other leavens can be quick-started with a small amount of rye sourdough. For instance, instead of starting a spelt leaven from scratch, which would take at least 4 days according to the schedule given above, you can get one going overnight. The sequence and quantities would look like this:

Rye-seeded spelt leaven

20g Old Rye Sourdough Starter (page 160)

70g Wholemeal spelt flour

60g Water

150g Total rye-spelt starter

Keep this mixture as near to a constant 28°C as you can manage. Ferment for 12-24 hours. This then becomes the Spelt Starter in Stage 1 of the Spelt Production Leaven on page 195. The rye sour content of the refreshed Spelt Production Leaven is only 4.2 per cent and it is only 1.27 per cent of the final spelt dough, so the rye flour will not have any negative effect on the texture of the loaf. Indeed, small amounts of rye flour actually benefit the handling and eating quality of wheat and spelt doughs.

The same principle can be applied to any sourdough or leaven. Purists might argue that the yeasts and lactobacilli in rye are subtly different from those in other grains and flours and they may be right. But starting a wheat leaven with an initial population of organisms from a rye sour clearly works and does not preclude the probability that other yeasts and bacteria would emerge if that leaven were henceforth to be refreshed only with wheat flour.

The next loaf shows how easy it is to use a basic rye sourdough to make wheat bread – and how good it can be.

Cromarty Cob

This recipe may have come about because of my forgetfulness, but it has become one of my favourite ways of making bread. It is just so easy and the result is a loaf of wonderful flavour with a terrific crust.

In Cromarty, on the Black Isle just north of Inverness, Sutor Creek community restaurant serves wonderful pizzas from a wood-fired oven built by my Cumbrian colleague, Alf Armstrong. I was invited to run a breadmaking course for local people in the restaurant. I arrived the evening before and realised that I had forgotten to bring my wheat leaven starter. There was no time to create another one from scratch but a naturally leavened French Country Bread was one of my key course recipes. What to do? As I was stirring fresh flour into the rye sourdough that would be used for Borodinsky the next day, I realised that the solution was literally in my hands. Why not use some rye sour to refresh a wheat leaven? It worked perfectly. It is true that relief at not having my forgetfulness exposed may have coloured my judgement, but the Cromarty loaf seemed to have a particularly delicious chewy crumb and tangy crust.

So this recipe shows how an old rye sourdough starter can be used to refresh a wheat leaven and make a light wheat loaf. The rye flour content of the final dough is less than 5 per cent, but the lactic acid bacteria brought in with the original rye sourdough have a significant effect on the flavour of the bread. I have suggested using a mixture of strong white and plain white flour in the final dough in order to produce a weaker, more extensible gluten structure. This could equally well be done by using a white flour stoneground (and sifted) from English wheat, or indeed a French T110 flour. If you prefer a more intensely flavoured and more nutritious bread, use more wholemeal in the leaven and some or all in the final dough.

The production leaven

150g Rye Sourdough Starter (page 160)

100g Stoneground wholemeal flour

100g Strong white flour

100g Water

450g Total

The rye sourdough starter does not have to have been recently refreshed. Provided that you are confident that it has at some time been a reasonably vigorous sour, it should revive quickly once it has access to fresh flour and warmth.

Mix everything together into a fairly firm dough at about 27°C. Cover and leave in a warm place for 3-4 hours. This rye-started leaven may ferment a bit quicker than an all-wheat one. It is ready when it has expanded appreciably, but try to use it before it has collapsed back on itself.

Cromarty cob dough

200g Strong white flour

200g Plain white flour

7g Sea salt

300g Water

300g Production Leaven (from above)

1007g Total

Make a dough with all the ingredients except the refreshed production leaven. Knead until the gluten is showing good signs of development. Then add the refreshed leaven and continue kneading for a few more minutes. At the end of kneading the dough should be soft and stretchy and coming away from your hands, but it should not be so firm that it doesn’t stick to the worktop if left for a few seconds.

Moisten an area of worktop with water, put the dough down on it and cover it with a bowl. From this point, fold, mould and prove as for French Country Bread (page 184-185). When you tip the proved dough out of its basket on to a baking tray or peel (a baker’s flat shovel for sliding loaves into the oven), cut it with a single large ‘C’, for Cromarty. Curved cuts are a bit tricky, but this one will make a nice break in the top crust – and it will be a kind of homage to the good people of Sutor Creek and their wood-fired oven.

Making sourdoughs work in real life

Sourdoughs and leavens may be fundamentally simple to make, as I hope I have demonstrated, but fitting this kind of breadmaking into domestic life takes a bit of figuring out. Once you get your head round the basic sequence of events, you can decide when to start (or aim to finish) the process of making a naturally fermented bread.

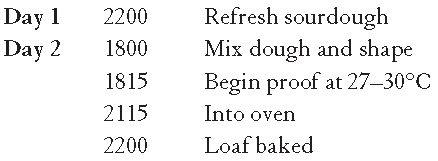

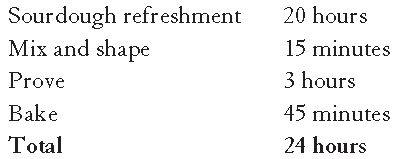

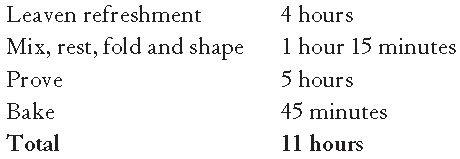

Even now, if I have a dough to prepare for a course or a new product experiment, I write down on a scrap of paper the sequence of starter refreshment, production sourdough and final dough with approximate timings. I find it helps to keep me straight. Below are some typical timings as examples that you may wish to follow, and also to show how you can control the process by adjusting the dough temperature.

The basic sequences for making bread with a rye sourdough or a wheat leaven at normal kitchen temperatures go like this:

RYE SOURDOUGH SYSTEM

WHEAT LEAVEN SYSTEM

The timelines below show how this works in real life. These are, of course, only guideline timings. A rye sourdough can be used to make a final dough at any time after about four hours, depending on the temperature and the liveliness of its yeast population. The yeasts tend to reproduce and ferment quicker than the lactic acid bacteria, so a young sourdough will be noticeably less acidic. Similarly a wheat leaven may be ready to use in as little as two and a half hours in very warm weather. Proof times, too, will vary with the ambient temperature and the general vigour of the sour or leaven being used.

I use the 24-hour clock because it makes it easier to keep track of day and night. Obviously the start times are just suggestions and can be changed at will.

CLASSIC RYE SOURDOUGH SYSTEM