Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (45 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

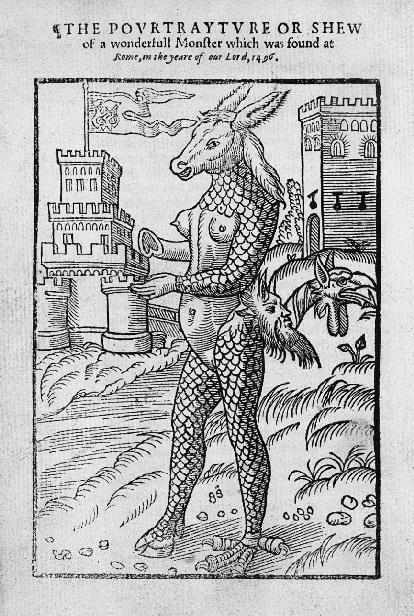

In 1523 Luther and Melanchthon had an enormous success with a pamphlet interpreting two such signs, the so-called monk calf (a misshapen calf fetus) and the “Papal Ass,” a strange beast washed up in the Tiber in 1495.

17

This scarcely contemporary event was now interpreted as a clear foreshadowing of the corruption of the papacy. The pamphlet, published by Rhau-Grunenberg, was rapidly reprinted all over Germany.

18

Its success no doubt owed something to Cranach’s arresting images, but it also caught the mood of the moment. In the mid-1520s the turbulence of the Reformation combined with the general sense of apocalyptic expectation to create a widespread fear of impending catastrophe. It was forecast that in 1524 Germany would experience a deluge comparable to the Great Flood. While sharing the general mood of apocalyptic tension, Luther counseled against too precise an attempt to tie the end-time to a particular moment. His endorsement of Lichtenberger’s prophecies was careful and measured:

I think the basis for his astrology is correct, but the science is uncertain. That is, the signs in the heavens and on earth do not err; they are the work of God and of the angels; they warn and threaten the godless lords and countries, and they signify something. But to found a science upon them and to place it in the stars—there is no basis for that.

19

When in 1533 his friend and protégé Michael Stifel announced a precise time for the end of the world (8

A.M.

on October 19), Luther strongly disapproved. Crowds streamed into Stifel’s village of Lochau to share the moment of rapture. When 8

A.M.

came and went without incident, Stifel

was quickly removed to Wittenberg to protect him from the anger of his disappointed followers. He would spend two years of reeducation in Luther’s house before being quietly reassigned to a new parish.

20

T

HE

P

APAL

A

SS

Luther and Melanchthon had one of their greatest successes with their descriptions of the monk calf and Papal Ass. This version is from an English translation, published more than fifty years later.

Luther reacted with understanding and generosity to Stifel’s enthusiasm partly because he shared the fundamental conviction that these were indeed the last days. This apocalyptic vision helps explain both the tone and preoccupations of his late polemics, particularly his late-blossoming engagement with the Turkish threat.

Luther’s first reaction to the seemingly invincible Turkish horde was to regard it as God’s scourge, a just punishment visited on Christendom for having tolerated the papal Antichrist.

21

This laid him open to the charge, duly made in

Exsurge Domine,

that Luther believed that “to fight against the Turks is to oppose God’s visitation on our iniquities.” Never one to give ground in such circumstances, Luther reiterated his belief that war against the Turks was futile as long as the papacy remained. But as Turkish armies continued their inexorable march through Christian territory, and particularly after the calamitous slaughter of the Hungarian nobility at Mohács, Luther was forced to a more considered reflection on the clash of civilizations. The siege of Vienna of 1529, a milestone in German resistance to the Ottoman armies, called forth two substantial works,

Concerning War

Against the Turks,

and the

Army Sermon Against the Turks

.

22

Here Luther conceded the need for military resistance, though the true solution still lay in spiritual repentance. These works are also notable for Luther’s clear identification of the true identities of the papacy and the Turk: the papacy was Antichrist, the Turk the Devil itself.

This revelation, reinforced by Luther’s study of the apocalyptic prophecies of the Book of Daniel in 1530, shaped his treatment of the Turkish threat when he returned to the subject in his last years. The respite provided by the relief of Vienna had proved short-lived; the Turkish host was on the march once more. In 1541 Suleiman captured Buda and Pest and invested Hungary. John Frederick called upon Luther to rally the congregations of Saxony for prayer against the Turks. Luther’s response, the

Admonition to Prayer Against the Turks,

was dark in tone.

23

Clearly identifying the Turk as the beast of Revelation, Luther called above all for repentance. The German people had received the Word of God; it was their ingratitude that had caused God to send this new plague. This line of argument was developed further in two important short statements published as preface and afterword, one to Brother Riccoldo’s

Refutation of the Koran,

and the other to Bibliander’s edition of the text. The preface to the Koran edition was Luther’s letter to the Basel

Council urging that publication be permitted; it is not clear whether Luther expected to see it printed. Here he made a clear case that it was necessary to know the enemy.

We must fight everywhere against the armies of the Devil. How many different enemies have we seen in our own time—the defenders of the pope’s idols, the Jews, a multitude of Anabaptist monstrosities, the party of Servetus and others. Let us prepare ourselves against Mohammed as well. But what will we be able to say concerning things of which we are ignorant? That is why it is beneficial for learned people to read the writings of their enemies.

24

In the preface to Riccoldo he warned against concluding that the Ottomans’ military success meant that they enjoyed God’s favor. “This does not happen because the faith of Mohammed is true and our faith is false, as the blind Turk boasts. Rather, this is the manner in which God rules his people.” Most of all, it was a judgment on a people who continued to tolerate the papacy, “our Christian Turks.” At least the Mohammedans were ignorant of the truth of God’s word. “But our Christian Turks have God’s Word and preachers, yet they do not want to hear it.”

25

The moral was clear:

I do not consider Mohammed to be the Antichrist. He acts too crassly and has a recognizable black devil, which is incapable of deceiving either faith or reason. He is like one of the heathen, who persecutes Christendom from without, as the Romans and other heathen have done. . . . But the pope among us is the true Antichrist.

26

This was the last occasion on which Luther addressed the issue in print. But the Turkish threat was never far from his thoughts in these last days. On January 31, 1546, in one of his last sermons, Luther spoke of the trials of the church, tossed on the sea of tribulation like the apostles on the Sea of Galilee. The Turk was prominent among the Devil’s agents.

27

LAST BATTLES

The Turkish onslaught during Luther’s last years was for the reformer just one more confirmation of the truth that had framed his career: that he, and his suffering fellow Christians, were living through the last days plainly foretold in Scripture. Aware that his own days were numbered, Luther was ever more conscious that his bodily failings were mirrored in the threats assailing his young and fragile church: the looming danger of the emperor’s revenge; quarrels among the princes; the gathering forces of Antichrist. Ever more clearly he saw his own prophetic role, to call the Christian people to repentance, to nurture the dismally small number who had heeded the call to follow the Gospel.

This mental and physical world was the context in which Luther fought his last battles. Luther saw it as his inescapable duty to parry the Devil’s thrusts, by smiting all of his servants: the papists, those false brethren who had betrayed the Gospel, the Turks, and the Jews. This last group had, until this point, occupied very little of Luther’s attention. There were at this date relatively few Jews in Germany; Luther’s own community in Wittenberg had expelled its Jewish population some ninety years before his arrival. In Wittenberg the memory lived on in the Judengasse, a thoroughfare on the city’s northern periphery where many of those employed in the book trade were now settled.

Luther did not aspire to the expertise in Jewish questions of, for instance, his old adversary Johann Eck, who writing in the 1540s would claim firsthand knowledge of a sensational case of ritual child murder that had taken place in Freiburg im Breisgau in 1503. Eck recounted this story in his

Refutation of a Jewish Booklet,

a response to an attempt by the Protestant reformer Andreas Osiander to debunk such claims of ritual murder.

28

Luther’s first utterance on the Jewish faith was, in marked contrast to Eck, extremely measured.

29

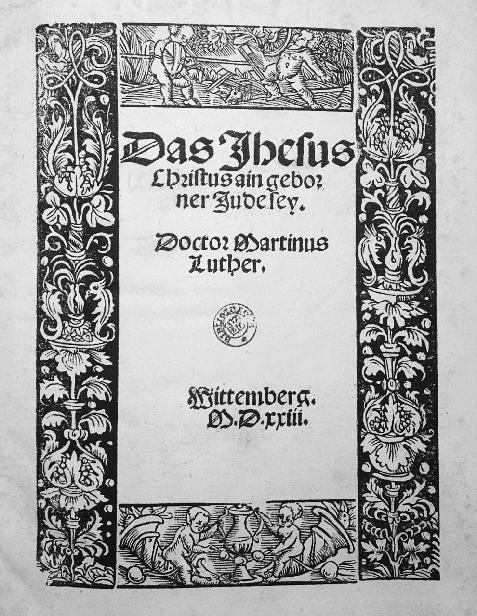

His treatise from 1523,

That Jesus Christ Was Born

a Jew,

was essentially a lament

that the current Christian hierarchy impeded any attempts to bring Jews to Christianity:

For our fools, the popes, bishops, sophists, and monks—the gross asses’ heads—have treated the Jews to date in such a fashion that he who would be a good Christian might almost have to become a Jew. And if I had been a Jew and had seen such oafs and numbskulls governing and teaching the Christian faith, I would have rather become a sow than a Christian.

30

With this Luther turned to other theological concerns, returning to the matter only in 1538 with an open letter

Against the Sabbatarians

.

31

This far more pugnacious text seems to have been partly stimulated by a shadowy meeting in 1536, when three learned Jews called upon Luther in Wittenberg to probe him on his interpretation of certain passages in the Old Testament. The reformer may have got somewhat the worse of this encounter; certainly his rather grumpy reference to his own personal experience of their stubborn refusal to be persuaded suggests that it left rather an acid taste. Even so this small and rather modest work does little to prepare us for the violent and intemperate tone of Luther’s most notorious work,

On the Jews and Their Lies

.

32

This was the first of three writings that Luther devoted to Jewish beliefs and teachings in 1543; they can, in fact, be treated as three parts of one major contribution to the debate, although Luther, characteristically, allocated them to three different Wittenberg printers, Lufft, Rhau, and Schirlentz. The second and third tracts,

On the Ineffable Name

and

On the Last Words of David,

both offer important discussions of teachings in the Old Testament that in Luther’s view attested to the truth of Christianity (on the Trinity and the Virgin Birth).

33

The second part of the trio,

On the Ineffable Name,

was by far the most successful in publishing terms, though it is

On the Jews and Their Lies

that has attracted the most attention, not surprisingly, given the violence of its language. Although Luther claimed here that he had reentered the debate with the greatest

reluctance, his advice to Germany’s princes was uncompromising. The Jewish presence in Germany was a plague that should be eradicated; synagogues should be destroyed and Jewish books confiscated. None should suggest that the Jews were indispensable for financial reasons; now was the time to remove them from Germany.

THAT JESUS CHRIST WAS BORN A JEW

Luther’s first, very measured pamphlet on the Jewish faith. This edition, despite the addition of Wittenberg to the title page, was published in Augsburg.