Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (29 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

Luther’s fellow “evangelists” were among the first to benefit from his imprimatur. In the case of Melanchthon, Luther’s first intervention did not entirely redound to the reformer’s credit, since he had sent Philip’s lectures on Romans and Corinthians to the press without the author’s permission. Melanchthon had been reluctant to publish this work despite Luther’s frequent urgings, so Luther dispatched his own copy to a friendly Nuremberg printer, along with his own slightly shamefaced letter of dedication to the reluctant author.

23

Presumably it had not been given to a Wittenberg printer in case Philip stumbled upon it: Melanchthon, like Luther, would have been a frequent visitor to the printers’ workshops. Given he was also a steady source of work for the Wittenberg printers, none of them would have been entirely comfortable printing one of his works without his permission. In the event, this devious stratagem backfired badly as the Nuremberg printer made rather a mess of the task, publishing an edition so full of errors that these could only partially be corrected in subsequent editions. Had this happened to Luther’s own work he would have been furious. In this case he decided to brazen it out, dispatching a further set of Philip’s lectures (on John’s

Gospel) for printing in Hagenau, complete with a letter of dedication to his friend Nikolaus Gerbel:

I have already purloined our Philip’s Annotations on three Epistles of Paul. And though he was not at liberty to rage against that thief Luther for it, he nevertheless thought he had been most satisfactorily avenged against me in that the little volume had come out so full of errors due to the negligence of the printers that I was nearly ashamed and regretted having invested my stolen property so poorly. Meanwhile, he has been making fun of me, hoping that henceforth I would abstain from such theft, having been taught a lesson by my predicament. But I, not troubled at all by this derision, have grown even more audacious, and now I take his Annotations on John the Evangelist not by stealth but by force, while the author resists in vain.

24

All of this was rather tongue in cheek, but whether Philip saw the joke we do not know. The choice of Hagenau was an olive branch of sorts, since the text was consigned to Johann Setzer, the son-in-law of Thomas Anselm for whom Melanchthon had worked in his youth in Tübingen. Young Setzer rose to the occasion, as the title page proudly proclaims:

The Annotations on John of Philip Melanchthon, more correct than those previously published, inasmuch as in this edition are contained many things missing from the others, along with a letter of commendation by M. Luther and an index.

25

This rather extended history of Luther’s imperious commandeering of his colleague’s work is worth recounting, because these volumes introduce several features that would be quite characteristic of the works published with Luther’s endorsement. First, they were frequently put to

the press outside Wittenberg. Just as Melanchthon’s works were sent to Nuremberg and Hagenau (and immediately reprinted elsewhere), so Bugenhagen’s lectures on the Psalms were published in Basel. Second, Luther’s letters of dedication were frequently addressed not to the author himself but to a third party, as here to Nikolaus Gerbel. Both features advertised to the reading public the expanding circles of those committed to the Wittenberg cause, in the German print world and among its leading intellectuals. Finally, we see Setzer’s astute reference to Luther’s involvement on the title page. Whatever the author’s own reputation (high in Melanchthon’s case) the advertisement of Luther’s participation could only increase the book’s salability.

In the course of the next twenty-three years Luther would provide a preface for over ninety works: the last, in 1545, adorned a posthumous edition of the English reformer Robert Barnes, whose

Lives of the Roman Pontiffs

Luther had enthusiastically endorsed in 1536.

26

Sometimes he clearly found it rather burdensome: as he wearily remarked in 1537, “I must now be a professional writer of prefaces.”

27

Some were dashed off rather hurriedly, and amounted to no more than a couple of rather bland paragraphs. This was not his most considered work. But Luther was probably well aware that it was not the substance of his remarks but the mere fact that he offered his endorsement that elevated the book in the eyes of purchasers and book-trade professionals.

These prefatory remarks do, however, offer an interesting barometer of Luther’s preoccupations as the movement shifts from the early direct engagement with the papacy to a period of consolidation and church building. Some preoccupations are enduring: the Turkish threat, the defense of matrimony, and particularly clerical marriage. Luther also sometimes uses a preface to signal an adjustment to previous literary missteps. The sea change in his attitude to Jan Hus and the Czech Unity of Brethren is reflected in several prefaces from the 1530s in which he wrote candidly of his earlier blindness to the virtues of the Czech reformer. A preface to twenty-two trenchant sermons by Johann Brenz published in 1532 also allowed him to distance himself from earlier remarks that seemed to

advocate nonresistance against the Turkish invaders.

28

Throughout his career Luther was restlessly preoccupied by the Turkish threat to European Christendom, but aware also of his own ignorance of the Muslim faith. In 1530, introducing George of Hungary’s description of Turkish ceremonies, he confessed that he had not yet been able to procure a translation of the Koran. When in 1542 this was finally furnished by the publication in Basel of Theodor Bibliander’s translation, Luther intervened directly to ensure the success of this controversial project, writing to the Basel Council to secure the freedom of the incarcerated printer Johannes Oporinus, and providing a preface for publication.

29

Luther was deeply obliged to the radiating circle of clergy and laypeople who committed themselves to his cause; he realized that their wholehearted commitment, their theological expertise and literary virtuosity, was vital to his survival. These prefaces show how he nurtured and tended this community to ensure that the Reformation would not stand or fall “by Luther alone.” It is one of the most fascinating and understated aspects of his lifelong engagement with the printing industry.

THE WORD OF GOD

One collective effort towered above all others in the Wittenberg pantheon: the translation of the Bible. When Luther embarked on the work of translating the New Testament during his last weeks in the Wartburg, he was always clear that this enterprise would be shared with others. Even in beginning the task, he frankly acknowledged to Amsdorf, “I have here shouldered a burden beyond my powers.”

30

Luther had no sense of proprietorship for this work. When he heard that his friend Lang was engaged on a Bible translation at Erfurt, he urged him to continue: “I wish every town would have its interpreter.” Although he completed his first translation of the New Testament in eleven weeks, he knew he could go no further without help; a large part of his reason for bringing forward his return to Wittenberg was to engage his friends in this task.

So urgent was this in his mind that at one point he contemplated returning secretly and taking a room somewhere in Wittenberg, where he could remain closeted with the translation work and have his friends make clandestine visits to offer their help.

This, of course, was a pipe dream. In the event, Luther would make a very public return to his pulpit and place of authority within the church. But the work with the Bible was soon resumed. It would engage Luther, his colleagues, and his friends in the Wittenberg publishing industry for the best part of a further twelve years.

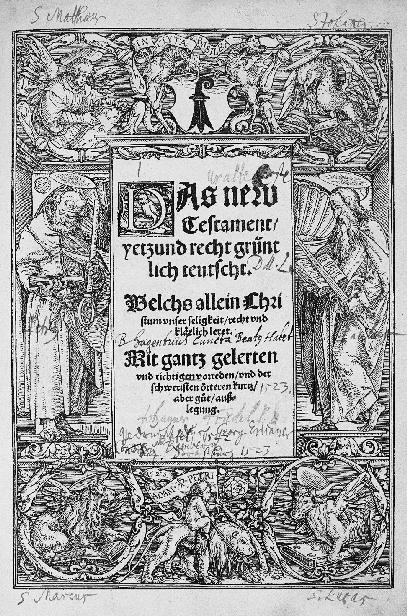

First there was the publication of Luther’s New Testament to be supervised. Notwithstanding Luther’s modest words of self-deprecation to Amsdorf, there was little time for fundamental revision of his work before the text was passed to the printer. Between Luther’s dramatic return from the Wartburg on March 6 and the setting of the first sheets was only two months, time enough only for a final review of the text in the company of Philip Melanchthon. The timetable Luther set his printers was equally hectic. The completed work was to be ready by September, in time for sale at the Frankfurt Fair (it has become known, in consequence, as the September Testament).

The Frankfurt Fair was by this time Europe’s principal emporium for the wholesale trade in books, dwarfing the other major seasonal fairs established over the course of the previous centuries. It took place twice a year, at Easter and in September, and was attended by publishers and booksellers from all of Europe’s major book markets.

31

It was a mark of the growing maturity of Wittenberg’s book industry that it was now organizing its production timetable around the established biannual fairs; notable, too, that by dealing with Frankfurt, Wittenberg’s printers were able to bypass the previously dominant regional market at Leipzig, the now ailing local rival.

A good sale at Frankfurt was considered critical, since it had been decided that the September Testament should be published in a huge edition of some three thousand copies. This was an extremely tall order. The Wittenberg printing industry had grown very substantially in the last

five years, particularly when measured in terms of output. But its printers had never taken on a task of this size and complexity. Most of Luther’s writings were short and relatively simple tasks for a printer. This on Luther’s part was quite deliberate. He was spreading the word to an audience with many inexperienced readers. He also knew Rhau-Grunenberg’s limitations: when the printer had attempted something more demanding, like the Psalm commentaries, he had quickly got into trouble.

Melchior Lotter had brought greater professionalism, but the industry’s capacity was still limited, and fairly stretched just keeping up with the steady stream of new works emanating from Luther’s own pen. In the summer of 1521, according to Luther, there were six presses operating in Wittenberg. This probably equates to four in Lotter’s shop and two in that of Rhau-Grunenberg. But as Luther only half flippantly remarked, these were kept pretty busy, four publishing his own works, and one each for Melanchthon and Karlstadt.

32

Now space had to be found for the Bible project, a book of serious size, heavily illustrated in significant portions of the text. For Lucas Cranach had prepared for this milestone text one of his masterpieces: a series of full-page woodcuts with which to dramatize the vivid prophecies of the apocalypse.

33

Custom and use also demanded that the New Testament be published in the large, folio format, almost the first book that the Wittenberg presses had taken on in this larger size.

For all these reasons the publication of the New Testament needed to engage the best talents available in the Wittenberg printing industry. Inevitably Rhau-Grunenberg was bypassed for a task of this complexity. The Bible project was consigned to Luther’s reliable partners Christian Döring and Lucas Cranach, using Melchior Lotter’s presses. Only this combination, working together, offered the prospect of bringing it to a successful conclusion. Döring could provide the necessary investment capital. Cranach’s paper mill could furnish the raw materials, his workshop the woodcuts. Melchior Lotter would manage the work through the press. Then Döring’s transportation firm could deliver the stock to Frankfurt.

Somehow Lotter managed to clear three presses of other tasks and the work began. The schedule was almost impossibly daunting, but Cranach and Lotter were both hard, driven men. The presses were cajoled into producing the required number of printed sheets; at least in Cranach’s vast factory workshop there would have been no problem with storage space or with recruiting extra hands to stack and collate the finished sheets. On May 10 the first fascicule was completed.

34

Work progressed steadily through the Gospels and Epistles, at first in some secrecy, since the publishers had no wish to be preempted by another printer getting hold of the parts and creating his own competing edition. By September 21, miraculously, the whole edition was finished and Luther could send the last parts to Spalatin, which gave him three complete copies: one for himself, one for the elector, and one for Duke John.

35

The rest of the edition was now released for local sale and shipping to Frankfurt; and just as swiftly it was gone, sold out. Lotter began immediately with a new edition, to be published in December with Luther’s hurried corrections and improvements. But the market was insatiable, sufficiently robust for Adam Petri to publish his own folio edition by year’s end at Basel.