Brain Lock: Free Yourself From Obsessive-Compulsive Behavior (4 page)

Read Brain Lock: Free Yourself From Obsessive-Compulsive Behavior Online

Authors: Jeffrey M. Schwartz,Beverly Beyette

So you have OCD. What can you and your doctor do to make those awful urges and compulsions go away?

The core message in treating OCD is this:

Do not make the mistake of waiting passively for the ideas and urges to go away

. A psychological understanding of the emotional content of the thoughts and urges will rarely make them disappear. Succumbing to the notion that you can do nothing else until the thought or the urge passes is the road to hell. Your life will degenerate into one big compulsion. Think of the analogy of the insistent car alarm that annoys you while you are trying to read a novel or magazine. No matter how annoyed you are, you are not going to sit there and say to yourself, “I’m going to make that alarm turn off and I’m not even going to try to read this until it does.” Rather, you’re going to do your best to ignore it, work around it. You’re going to put your mind back where you want it and do your reading as well as you can. You’ll become so absorbed in what you’re doing that you hardly notice the alarm. So by focusing your attention on a new task, what would otherwise be extremely annoying and bothersome can be worked around and ignored.

Because OCD is a medical condition—albeit a fascinating one—and is related to the inner workings of the brain, only a change in the brain itself, or at least in brain chemistry, will bring about lasting improvement. You can make these changes through behavior therapy alone or, in some cases, behavior therapy in combination with medication. However, medication is only a “waterwings” approach to OCD therapy; it will help you stay afloat while you learn to swim through the rough waters of OCD. At UCLA, medication is used only to help people help themselves. But the underlying principle is:

The more behavior therapy you do and the more you apply the Four-Step Method the less medication you’ll need

. This is especially true over the long haul. (Behavior therapy is discussed in detail in Chapter Eight and medication in Chapter Nine.)

In developing a new approach to treating people with OCD, our research team thought that if we could make patients understand that a biochemical imbalance in the brain was causing their intrusive urges, they might take a different look at their need to act on those

urges and strengthen their resolve to fight them. A new method of behavior therapy might result.

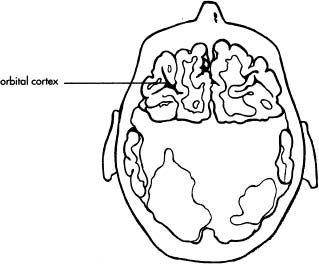

To help patients understand this chemical imbalance, we showed them pictures of their brains at work. During a study of brain energy activity in people with OCD, my colleague, Dr. Lew Baxter, and I took some high-tech pictures using positron emission tomography, or PET scanning, in which a very small amount of a chemically labeled glucoselike substance is injected into a person and traced in the brain. The resulting pictures clearly indicated that in people with OCD, the use of energy is consistently higher than is normal in the orbital cortex—the underside of the front of the brain. Thus, the orbital cortex is, in essence, working overtime, literally heating up. (Figure 1, opposite, shows a PET scan—presented in color on the cover of this book—of a typical OCD patient. Note the high energy use in the orbital cortex, compared to that in a person who does not have OCD.)

We already knew that by using behavior therapy we could make real and significant changes in how people cope with their urges. Perhaps, we reasoned, we could use these visually striking pictures of the brain to help inspire people with OCD. Since a brain problem appeared to be causing their intrusive urges, strengthening their will to resist the urges might actually change their brain chemistry, in addition to improving their clinical condition.

Benjamin, a 41-year-old administrator in a large school district whose brain photos are pictured later, in Figure 3, suffered from a compulsive, time-consuming need to have everything in his environment clean and orderly to an abnormal degree. He recalls vividly having his brain photographed and then being shown proof that it was overheating. “Boy, was that a real jolt!” he said. “It was very distressing to learn that I had a brain disorder, that I wasn’t perfect. Initially, it was very difficult to accept.” At the same time, seeing the picture was critical to his understanding that he had OCD, in his words, “incontrovertible evidence that I had a brain disorder.” In our program at UCLA, Benjamin mastered the Four Steps of cognitive-biobehavioral self-treatment, and today, six years later, his symptoms are largely under control and he is functioning well, both professionally and in his personal relationships.

Figure 1. PET scan showing increased energy use in the orbital cortex, the underside of the front of the brain, in a person with OCD. The drawings show where the orbital cortex is located inside the head. The arrows point at the orbital cortex.

Copyright © 1987 American Medical Association, from

Archives of General Psychiatry

, March 1987, Volume 44, pages 211–218.

Understanding the difference between the form of OCD urges and their content is the first step toward understanding that brain malfunction is the main culprit in these urges. Remember Barbara and her obsessive worry about Mr. Coffee? She was being driven to distraction, worrying whether she’d turned off that machine. That was the content of her obsession. Superficially, that was her problem. But in treatment, it soon became obvious to her, and to us, that the real problem was that she couldn’t rid herself of the

feeling

that Mr. Coffee might still be on. That she was plagued by that worry hundreds, even thousands, of times a day gave us an important clue to the mystery of OCD: She could have that all-consuming worry even while holding the unplugged cord from Mr. Coffee in her hand!

Likewise, Brian knew that a brand-new battery was not going to leak acid. Still, if someone placed a battery on his desk, he freaked out: “The kid who worked with me said he saw guys under fire in Vietnam who didn’t have the fear in their faces that I had.”

And Dottie knew that her son was not going to go blind if she didn’t perform a certain compulsion. But if she happened to see a TV show about a person who was blind, she’d have to jump in the shower, clothes and all.

What really worried Barbara, Brian, and Dottie was how they could be so worried about something so ridiculous.

We will probably never know why Barbara became fixated on Mr. Coffee, Brian on battery acid, or Dottie on eyes. Freud’s theories may provide clues, yet Freud himself believed that these types of problems stem from “constitutional factors,” by which he meant biological causes. Today, most psychiatrists in the Freudian tradition acknowledge that understanding the psychological content of these symptoms—the deep inner conflicts that lead one person to worry about causing a fire and another to fear that he or she will do something violent to someone—will do little, if anything, to make the symptoms go away. Why not? Because the core of the problem in OCD lies in its form, in the fact that the worrisome feeling intrudes repeatedly into the mind and will not go away. The culprit is a neurological imbalance in the brain.

Once people understand the nature of OCD, they are better armed to carry out the behavior therapy that leads to recovery. Just

knowing, “It’s not me—it’s my OCD” is a stress reliever that enables them to focus more effectively on getting well. From time to time, we remind them that they are not just pushing a rock to the top of a hill only to have it roll back down again and again. They are actually

changing

the hill. They are changing their brains.

IT’S WHAT YOU

DO

THAT COUNTS

The brain is an incredibly complicated

machine

whose function is to generate feelings and sensations that help us communicate with the world. When it works correctly, it’s easy to assume that “it is me.” But when the brain starts sending false messages that you cannot readily recognize as false, as happens with OCD, havoc can ensue.

This is where

mindful awareness,

the ability to recognize these messages as false, can help. We learned from OCD patients that everyone has the capacity to use the power of observation to make behavioral corrections in the face of the brain’s false and misleading messages. It’s like listening to a radio station that’s jammed with static. If you don’t listen closely, you may hear things that are misleading or make no sense. But if you make an effort to listen closely, you’ll hear things the casual listener misses entirely—especially if you’ve been trained to listen. Properly instructed in what to do in the face of confusing messages, you can find reality in the midst of chaos.

I like to say, “

It’s not how you feel, but what you do, that counts

.” Because when you do the right things, feelings tend to improve as a matter of course. But spend too much time being overly concerned about uncomfortable feelings, and you may never get around to doing what it takes to actually improve. Focus your attention on the mental and physical actions that will improve your life—that’s the working philosophy of this book, and the path to overcoming Brain Lock.

The Four Steps are not a magic formula. By calling an urge what it is—by Relabeling it—you cannot immediately make it go away. Excessive wishful thinking about immediate recovery is one of the biggest causes of failure, especially at the start of treatment. The goal here is not to make obsessive thoughts simply disappear—they won’t, in the short run—but, rather, to be in control of your responses to them. The behavior therapy guidelines you will learn

while doing the Four Steps will help you remember this crucial principle. You will gain control and change your brain mainly by using your new knowledge to mentally organize your behavioral responses and by learning to say, “That’s not me—that’s my OCD.”

The key to remember is this:

Change the behavior, unlock your brain!

KEY POINTS TO REMEMBER

•OCD is a medical condition that is related to a biochemical imbalance in the brain.

•Obsessions are intrusive, unwanted thoughts and urges that don’t go away.

•Compulsions are the repetitive behaviors that people perform in a vain attempt to rid themselves of the very uncomfortable feelings that the obsessions cause.

•Doing compulsions tends to make the obsessions

worse

, especially over the long run.

•The Four Steps teach a method of reorganizing your thinking in response to unwanted thoughts and urges: They help you to

change your behavior

to something useful and constructive.

•Changing your behavior changes your brain. When you change your behavior in constructive ways, the uncomfortable feelings your brain is sending you begin to fade over time. This makes your responses easier to manage and control.

•It’s not how you feel, but what you

do

that counts.

The Four Steps

W

ORDS OF

W

ISDOM TO

G

UIDE

Y

OU ON

Y

OUR

J

OURNEY

(in chronological order)