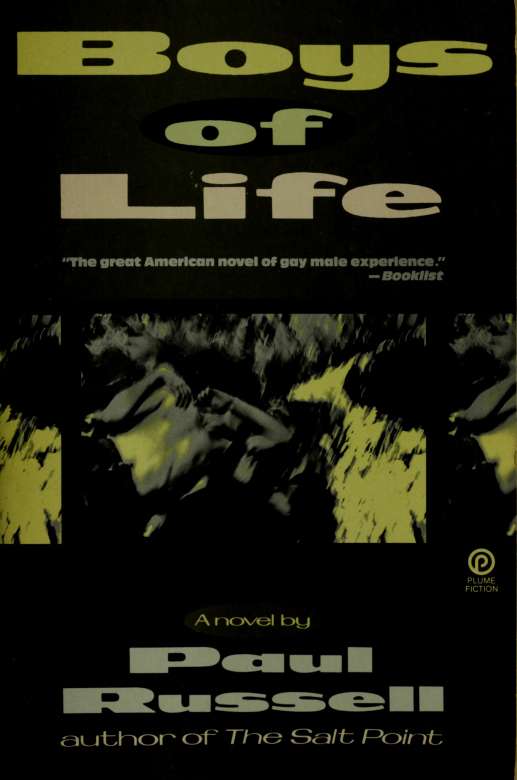

Boys of Life

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

To the memory of

Karl Keller

Robert Mapplethorpe

Pier Paolo Pasolini

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Harvey Klinger, my agent; Arnold Dolin, my editor; and Matthew Carnicelli, assistant editor. To Ann Imbrie, James Lewton-Brain, Catherine Murphy, Steve Otto, Bob Richard, Harry Roseman, and Michael Somoya, early and encouraging readers of this manuscript. To Matthew Aquilone, Christopher Canatsey, and Karen Robertson. To the late James Day, mentor, master-reader, friend. Especially to Tom Heacox. And finally to my lively and constant companions o{ Bar-hamsville, Abby, Darrell, and Sugar Baby.

Even if their adventures were sometimes so cruel as to be revolting by our standards, if they were obscene in such a grand and total way as to become innocent again, yet beyond their ferocity, their eroticism, they embody the eternal myth; man standing alone before the fascinating mystery of life, all its terror, its beauty and its passion.

— FEDERICO FELLINI

D PAULRUSSELL

where, some ocean, it really was the season for tropical depressions and storms.

I was tugging bed sheets out of the dryer, stuffing them back in the plastic garbage bags I'd brought. When I looked up, this man was staring at me. He was sitting on the wooden bench that ran along the windows in the front of the place, and he had a little spiral notebook in his lap, the kind you buy for school. He must've been writing something down, only he'd stopped and was looking around. I guess he'd seen me because he was staring, and when I glanced up we were looking right at each other.

I expected him to look away, but he didn't, and for some reason I didn't either. But then I did, I went on folding those sheets. I had this feeling he was staring at me the whole time, and when I looked back at him it was true, he hadn't moved. It was this questioning look, like you give somebody when you think you might've seen them before, or you might know them but can't remember from where. Only he looked like he knew exactly who I was. That's what I felt—here was somebody saying, Oh, I know exactly who you are even though I've never seen you before. Like he'd been waiting to meet me tor a long time and he'd known he would—he just didn't know when or where it would happen and now here it was.

Maybe I'm making all that up, but I don't think so.

There wasn't anybody but us in the laundromat. I hadn't noticed

him till I noticed him staring at me. He was maybe forty years old, not

to flab anywhere hut tight like the head of a drum. With his high

cheekbones he looked like he might have Cherokee blood in him. His

black hair was combed back from his forehead, and he was wearing this

black long-sleeve ^hirt buttoned all the way up to the collar. Mis eyes black t< «.'s like country people sometimes have,

and 'li.it thm hard hollowed-out face. Only he wasn't ,in\ counm pel

son. I 1 finitely somebody from somewhere else*.

I kept on folding sheets, hut he w.is Starting to bother me. I telt

hke lu- was studying me, hut when 1 looked up again he'd gone \\\d riting in his little spiral notebook. |ust then, he looked up right when I w.i- looking at him u was like I was the "ne who'd been looking and noi the other w, ( \ around, and he'd caught me.

fh. . more ll animaPi

than .i i trt .iiiiiii. il th.u's always on the

in, the wt n tin- alert 1 Ike e>en here

D 2

B O Y S O F L I F E D

in this laundromat some keen sense oi smell in Kim was miffing out things other people wouldn't pick up on.

I pretended I was trying to see past his head to something passing

by on the street. All ot a sudden he came bolting up at me from where he was sitting. I must've looked surprised—he sort of raised his eyebrows in a friendly way and sailed right past me to the washing machines, where he started pulling out clothes and tossing them into the drvers. He probably opened up fifteen washing machines, nearly every one in the place, and threw his stuff across into that many drvers. I had to laugh—each time I thought that must be all o\ it, there was still another washer for him to open and pull clothes from. He stopped Loading the dryer and looked at me. What's so funny? was what that look said.

Before I knew I was going to say anything, I said, "You got a pretty big family."

"You might say that," he said. "You got a pretty big family vour-self." He was looking at the stack oi laundry I'd piled up—with my mom and my brother, Ted, and my two little sisters, there were five oi us. "You married?" he asked me.

"Do I look old enough to be married?" I said. I was sixteen.

"Around these parts," he told me, "sure. Don't you people marrv when you're about twelve years old?"

He had this sharp accent, and I knew then he had to be this total stranger to Owen. Nobody in Owen ever talked that way. It sounded sort of snide. I couldn't know at the time that was just the way he was with strangers; you'd never guess it, but he was this shy person really.

"Hey, just kidding," he said. "Don't you hate doing this ^tuff?" He took in the whole room. "I mean, isn't it the worst.'"

"It's pretty bad," I told him. "But you really do have a lot iA clothes. Using up all the washers in the place."

"See," he explained, "I'm doing laundry tor a bunch oi people."

"That's nice. How'd you get suckered into that?" I wanted to p.i\ him back for that line about my being married.

He looked at me with a kind oi odd look.

"Suckered?" he said.

"You know, doing everybody else's laundry tor them."

"Just think," he said, like u had any kind of connection with

anything, "we'd never've had this Stimulating conversation it I hadn't brought all their laundry in here."

"Yeah, right," I told him.

I'd finished putting my laundry into garbage bags, hut since if

D PAULRUSSELL

still raining outside I hopped up on a washing machine to sit and wait for it to stop. I wished it wasn't raining because I sort of wanted to be out of there. I was afraid this guy might talk to me some more, and I didn't really have anything else to say to him.

And I guess he didn't have anything else to say to me either—he finished shoving everything in the dryer and then went back to his bench and started writing in his notebook again. From where I was sitting on the washer I couldn't really see him. Not that I wanted to, but something kept getting the best of me and I'd look over my shoulder to where he was. But he was never looking up at me, which I was glad for. He just kept writing in that notebook.

I couldn't figure out what he could be writing, and I sort of wanted to ask him, but I didn't want to start us talking again—so I sat there trying to be as blank as I could and watched the rain, listening to it drum the roof and wondering if it'd take long to get a hitch back to the house, or whether I'd have to walk it in the dark. The more I thought about all that, the more depressed I got. Like everything else, it was something I seemed to be doing all the time with no stop to it.

I wondered where he could be from, what reason he was stopped in the Nu-Way Laundromat with more dirty clothes than practically the rest of the town put together. There was something I liked about him, the way he sat there writing in that notebook and never looking up ar me even though I knew he knew 1 was still there—some kind ot lonely feeling I got looking at him, some queasy kind of loneliness 1 knew from when sometimes I'd lie on my back on the ground and look into the sky wondering if it ever had an end to it and knowing it didn't.

If nagged at me, this feeling, which was win I kept glancing over at

huu the wav 1 did. Like maybe 1 could surprise something and then I'd know what it u.is 1 was looking for and not being able to find.

Pan oi it was, to be honest, I was just bored sitting there waiting for the rain to be over and watching the whole row of dryers with then

loads spinning behind ^lass and the rain JUSI kept on and linalU the

I h ped .i minute oi two and he hadn't made a move

"YoUl I t«>ld him.

"Thanks," he said. "You can go nou " He started tucking stufl

I told him. "I don't warn to

('re into the ■ "<

inch' •

D 4

B O Y S O F L I F E □

"It's just that I have to walk. It's easier to carry that u,i\." "Yeah sure," he laughed. "I know a garbage bag bllfl when I see one. Where do you have to walk.'"

"A ways," I said. I thought maybe he'd offer me a ride, but he

didn't, he just concentrated on Stuffing his bags tnil oi clothes. Okay, I thought, I'm out of here. It he sees me walking in the ram he can gel the point, or it he doesn't, then fuck it. But I didn't go. It was still raining, and I just sat there watching him stuff piles and piles oi clothes into his garbage bags, probably fifteen in all, till finally he was done. He looked over at me and grinned this tight grin, like something was paining him. "So," he said with that sharp accent oi his, "you want to help me stow these in the van? Since obviously you plan to sit there all night."

"I've done worse," I told him.

"Yeah? I want to hear about it."

I shrugged.

"No really, I do."

"How about giving me a ride home instead?"

We were lugging the bags out to his beat-up orange VW van in the parking lot. He opened up the back. "Careful," he said, "don't just go slinging things around. You'll break something."

"What's all that stuff?" I had to ask. The back of the van wis totally full of junk—worse than some handyman's station wagon.

"Equipment," he said. "Cameras and whatnot."

"You take pictures?"

He made some sound like "anngh."

"It's this movie project," he said. "All these clothes, they're tor my crew. They go through them like diapers. I was the only one not hung over today, so here I am."

"A movie project," I said. "Like what kind o\ movie project?"

"Like a movie movie. Like we're making a movie," he said i he piled the last bag on. It made a pretty impressive heap. "I'm Catlos Reichart," he told me all of a sudden. "I'm not famous, so don't pretend you've ever heard of me, because you haven't. Now hop in and let's go."

The front seat was as tilled up with junk .is everywhere else in that van—pieces of paper torn out iA \ spiral notebook and tools and empt\ beer cans and Barbie dolls missing an arm or a le

"Excuse the mess," Carlos said. "I didn't exactly expect to go ferrying local youth around town."

□ PAUL RUSSELL

"You never know," I told him. It got to me, the edgy way he had of talking—but at the same time I felt pretty easy with him. It was strange. I wasn't sure if he was pulling my leg about making some movie—but that was okay, he was still the most interesting person right at that moment that I knew in Owen.

"But let's talk about you," he said. "What I'm always curious about is other people. People who live in little towns and carry their laundry around in garbage bags. I don't know anything else about you except that. I'd like to, though. Maybe I'll write a movie about you."

"Some movie that'd be," I told him.

"Well, you never know," he said. "But right now—where're we going. 7 Where's home? Or we could go somewhere and talk. Surely you don't have to go home and cook dinner too? But are you hungry? What time is it? I have no idea of what time it is, but I haven't eaten all day—I'm starving. That pizza place serves takeout, doesn't it? What's the drinking age in this part of Kentucky? Ten? Eleven? We could get a six-pack and takeout pizza and live it up in the back of the van."

It almost made me laugh—he sounded like he was afraid it ho stopped talking I might say something, and then everything'd be ruined. Like I might bolt in between sentences. I never heard anybody like that before, and I guess it interested me.

"Sounds okay," I said, not knowing exactly what I was okaying out of all those things he said, but definitely excited by the prospect of some beer. I knew my mom wasn't coming in till late—it was a Friday, and lots of Fridays she was out all night. And my little brother, Ted. could take care of my sisters fine. He definitely had sense enough to heat up Something or other from a can.

We picked up a pizza and two six-packs and then drove a ways out

au n. where the road turned utf to Tatum'a Landing. You could put 1m. it- m tin- rivet then' it vmi wanted to there was thii concrete

'i rh.it lloped down into the water. With night Coming on, and tl

rain, n« >K

WIp vet .ill those bags full of laundry, hia

th, mt.. the back "t 'In van, Carlos laid, "Pretty i

II. .it leasi it's di!' I told him. which it waa definitely

th.it

morrow, wrhii h he

th oni'in w*) to relaxii irted

hool, vvh.it wm n like at home,

D 6

BOYSOFLIFE D

did I have a lot of friends? He kept watching my face the whole time he was talking, the way nobody evei watches von. Ik- kept asking me questions. I guess I was Bort o( flattered.

"Yeah, I go to school," I told him. "It's pretty feeble. I live out on Route 27—hack the other way out of town." Like Carlos could care less or anything.

"A farm?" he asked, like that was what he wanted it to he.

"Nah," I had to tell him. "It's just this trailer. It's me and mv mom, and I got a hrother and some sisters. It's okay, it's better than this house we used to live in that was falling down at the time."

"And where's your dad?"

I sort of had to laugh—I guess I never knew what else to do. "My dad," I said.

I hadn't talked to anybody about my dad in a long time—it wasn't something any of us ever talked about.

"I'm just this stranger," Carlos told me. "Don't say anything you don't want to."

"No, I got no secrets," I told him. "I don't care."

"Good—if you don't, I won't," he told me, again looking at me like he did all the time. I rememher wondering at the wav he kept looking.