Born to Be Brad (3 page)

Authors: Brad Goreski

I dreamed of being an adult, of being thirty years old, because that meant I would be my glamorous self somewhere far away. It’s funny to imagine an eight-year-old child starting every sentence with the phrase, “When I turn thirty…” But I did, because that was my magic age. I didn’t know where I’d be or what I’d be doing. But I knew there wouldn’t be gingerbread houses. I was dreaming of another world. Or

Another World

. I’d watch soap operas after school, and I was obsessed with Linda Dano, who played Felicia Gallant. Felicia owned the chic store in Bay City, and she loved herself a hat and a knee-length coat and a beaded smock, sometimes all at once. She was sophisticated, and I bought into the idea that hers was a very sophisticated boutique despite the cardboard backdrop. Soap operas are full of smoke and mirrors and glitter, but this became my idea of glamour.

My childhood misadventures didn’t end with catalogs or soap operas. Sometimes, when my mother left the house, I’d go into her closet and dig out the veil she wore to my christening. I’d twirl around, looking at myself in the mirror and thinking for the first time, “I’m pretty.” As you can imagine, my dad—a manager of a medical lab in nearby Oshawa—wasn’t exactly thrilled. But he didn’t pull away. He didn’t shame me. In fact, the opposite happened. In the third grade, when the boys at school were dressing like their favorite hockey players for Halloween, I dressed up like Madonna. I made the costume myself, using one of Barbie’s lace nighties as a glove. Sometimes you have to get creative and make things happen, even as a third grader, to get a message across. I wore a T-shirt cinched at the waist like a dress, and a pair of my mom’s heels, and, yes, lipstick. I’m sure my dad would have preferred it if I’d chosen another costume, like a fireman or a police officer. We lived in a subdivision called Apple Valley, and none of the other little boys there were wearing lipstick. But there was a lot of love in my dad’s heart. He put on a brave face, took my lace-gloved hand in his own, and dragged me around the neighborhood ringing doorbells.

It’s no surprise that when I think of my childhood, I see it in terms of shifting sartorial inspirations. I made bold choices. And not all of them good choices. A look back:

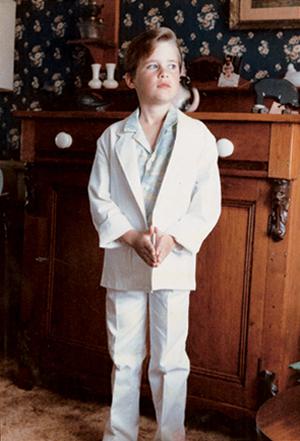

Age eleven: To my communion, I wore a white suit with a spread-collar, pastel-colored Hawaiian shirt. I had blond hair and I was going for a Don Johnson,

Miami Vice

moment. You can judge how successful this was for yourself by looking at this photo. But I considered myself to be the best-dressed in the Catholic church, by far.

My communion, 1989.

Age twelve: As a family, we went to see the Jacksons’ Victory Tour, and I was tenth-row center for Michael’s performance of “Beat It.” Thanks to some super-awesome special effect I’ll never quite understand—I like to think it was magic—Michael disappeared into thin air. My mind disappeared, too, when I spotted the Victory Tour T-shirt with baby-blue sleeves and an iron-on of Tito and Jermaine for sale. My parents bought this T-shirt for me, and I wore it to school for weeks, pairing it with black jogging pants that had zippers down the sides; when you opened the zippers neon yellow fabric peeked through for a pop of color. As if that wasn’t enough

look,

I tied a comic-book-print scarf asymmetrically around my waist. In case there’s any question out there, this was a big fashion don’t.

Age thirteen: I discovered Le Château, a store specializing in bold fashions in flammable fabrics. It was just another mall chain, but to me it felt like some terribly important Parisian boutique. The executives at Le Château’s headquarters I’m sure never guessed it, but this place was epic for a young gay kid looking for more than a pair of jeans and a T-shirt. It was the only store at the mall with anything that appealed to us. At thirteen, I bought a charcoal-gray Le Château shirt with a velvet number 5 on the front. Now, I know what you’re thinking. We’ve all had that moment: You’re out shopping one afternoon and you fall in love with a piece of clothing but think, Where am I going to wear a charcoal shirt with a velvet number 5 on the front? Well, in this case,

everywhere.

To drama club practice with a pair of jeans. To school with black velvet jean-style trousers.

Looking in the mirror back then I thought I looked super-cool, but the kids at school didn’t see it that way. Actually, they thought I looked like a huge fag. The F-word? Yeah, a bully first called me that in the third grade. That was only the beginning.

What Goes Around Comes Around

NEVER THROW ANYTHING AWAY. IT’S ALWAYS COMING BACK.

When J.Crew and Jil Sander both started selling bright colors for Spring/Summer 2011, I realized that old maxim really is true: What goes around comes around. Everything old is new again. This is why we have basements and storage units and deep closets; never throw anything away. Bass penny loafers? I stopped wearing them in high school when grunge came in, but they had a massive resurgence with the preppy movement in the mid 2000s. Speaking of grunge, as I write this, flannels and parkas are back in for a nineties moment. For women, denim jumpsuits and denim-on-denim (the Canadian tuxedo) are both socially acceptable again. If there’s one item from my past that I wish I’d saved, it’s an amazing

Les Misérables

T-shirt.

My sister, Mandy, refers to our childhood home as the Kennedy Compound. And it had an air of Hyannis Port about it. My grandfather Phillip bought a large tract of land on Lake Scugog and sold the subdivisions off to the family piece by piece. My parents and my sister and I lived in a house on Percy Crescent, with aunts and uncles and cousins on all sides. We could see my grandparents’ house from our backyard.

Everyone in town knew the Goreskis, because our grandfather Phillip owned the local resort, Goreski’s Lakeside Recreation, a trailer park in the best sense of the word. He started the business in 1963, and it grew to include eight hundred trailer sites plus boat slips and a marina, two swimming pools, and a miniature golf course. Families came annually for the entire summer. What were the people like? It wasn’t the chicest crowd. The boys wore Metallica T-shirts and jeans and bad high-tops, which at the time I found mildly offensive (however, in later years it would be a look I’d try to copy; things always come around). The young girls were scantily clad. And there I was in my polo shirt, cuffed jeans, and penny loafers, my hair always done. I stood out even at my family’s resort. As kids, my sister, Mandy, and I worked at Goreski’s Lakeside. She eventually ran the kitchen (as a teenager!), cooking up eggs, hamburgers, and fish-and-chips while I rang up the customers out front. For some people, working in a greasy take-out diner would be the worst summer job. But as an overweight kid, this was Candy Land—literally. I had access to all of the candy and ice cream I could eat. That is, until my uncle Ron fired me. I couldn’t blame him. Cadbury was running a contest, and I opened every single Cadbury caramel looking for the golden ticket. I was Canada’s answer to Veruca Salt. I want an Oompa-Loompa now, Daddy.

Burning question: Brad, please settle this once and for all. Is it OK to wear white after Labor Day?

This is one of those questions that persists over the ages. I have to say, I couldn’t care less. And neither could designers. I was in YSL and saw a gorgeous white cashmere coat. It’s called

winter white

for a reason. Because you’re supposed to wear it in the winter.

My sister had her own sense of style. Sometimes she dressed like a businessman, in a button-up and trousers. Other times she wore jeans and blazers. (She dresses the same way now.) Getting her to wear a dress and makeup became my mission in my youth. I succeeded once or twice; however, it never really took. I ended up wearing more dresses and makeup than she ever did. But she was my protector, and I am forever grateful to her. In grade five, for Halloween I dressed as the Wicked Witch of the West, which didn’t go over so well. I wore a black turtleneck, with a red sequined spiderweb on the front of it and a glittery spider stuck to the web. The skirt was this shredded mess of black and red fabric, and then I had a long cape on a black sequined headband. It was a riff, not an exact replica. Three boys from my class cornered me in the hallway and threatened to beat me up. Thankfully, a teacher came by and broke it up before they could land a punch. But my sister really let them know what was up. Out on the playground later that day, she tracked down those three boys and said, “If you’re planning on hurting anyone, you’ll have to answer to me first.” And then she pounded the crap out of them.

I was not the little boy from all of those television sitcoms—the one who tells his sister to back off, the one who insists he can fight his own battles. I just accepted that this was my lot in life. And I could no more change these boys than change who I was. Mandy was another of those superhero women in my life watching over me. Though I certainly didn’t make it easy for her. When she won the school’s citizenship award and she went up to receive the trophy, I stood up in front of all five hundred students and shouted with a lisp, “That’s my

sister

!” That was me. I was

dramatic.

I was the performer in the family. At the time, I was taking dance lessons. And when Grandpa Phillip had family over to the house, he’d parade me around the dining room saying, “Bradley, I’ll pay you five bucks to dance for me.” I happily took the five dollars, though I would have done it for free.

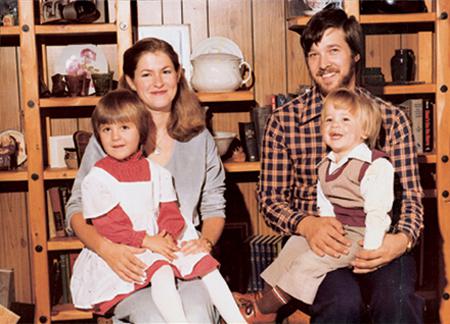

Christmas 1979 at my grandmother’s house. This is one of the few documented instances of my sister, Mandy, wearing a dress.

“That was me. I was

dramatic

. I was the performer in the family.”

My grandfather Harry, meanwhile, was a pharmacist and my mother worked in his office, putting on her starched white uniform every day. Sometimes I went to the pharmacy after school, sitting in the back, playing on the calculator and eating chocolate bars while waiting for my mom—anything to avoid riding on the school bus with the other kids. Though I could stomach the bus ride if it meant getting off at our grandma Ruby’s house. My sister and I would sometimes take the bus to her house, skipping down the hill, the smell from her kitchen getting stronger the closer we got. When I look back, I like to think I looked like Laura Ingalls in the opening credits to

Little House on the Prairie

as I ran down that hill, though maybe I looked more like Julie Andrews in

The Sound of Music

. But in reality, I was wearing a full snowsuit and moon boots, and I’d throw my head back and shout, “She’s making roast beef and steamed apple pudding!” Like most chubby kids, I had an excellent sense of smell. I was a cartoon character, Preppy Le Pew, floating on air to the kitchen.

When we arrived, Ruby would be sitting in her rocking chair or standing in front of the kitchen stove beyond the saloon doors. Their house was a fifteen-hundred-square-foot cottage, with a pump organ where I’d sit waiting for a snack, banging on the pedals. “Bradley, stop playing that goddamn organ!” Grandma Ruby would shout out from the kitchen. That’s how she spoke. She was a buxom woman, and vocal. We’d go shopping, and when my mother refused to buy me something I’d sometimes cry. Ruby would shout out, “Bradley,

I’ll

give you something to cry about!”

In a sometimes-rocky childhood, Ruby was the constant. When I was in kindergarten, our parents briefly separated. Though they soon reconciled, that threat of instability loomed over our house forever. Whenever our parents would have a big disagreement, my sister and I would ask each other, “Do you think they’ll get divorced?” But Ruby never wavered. She taught me to appreciate glamour. She had her hair done once a week, a permanent, of course. She was old-school in her charms. She preferred sensible shoes and cotton shirts with a cardigan over them, and a locket around her neck every day—work clothing, because what she did around the house was work. She was famous for baking. At Christmas, people couldn’t wait for her to drop off her famous cookie trays. But she was modern, too, especially in her unfailing acceptance of me. She took me to auction sales. She taught me how to act around the dinner table and how to act around adults. She had a toy room in her house with antique toys, model planes hanging from the ceiling and dolls everywhere, and we could play with them. She never criticized me for playing with dolls or Barbie, whom I loved because she always had somewhere to go. She always had a big date at night or an event. She barely had any day looks because she didn’t work. Barbie was all about night looks, and she existed to be glamorous. What is the impact of having your grandmother sit you down, put on a movie musical, and tell you anything is possible? I’m here to tell you it’s immeasurable.